The Global Temple

Raminder Kaur

‘If the Golden Temple is like the sun, the marble is like the moon.’

(Sukhwant, Amritsar, 2022)

Figure 1: Harmandir Sahib at sunset, Amritsar

There are reportedly 26-30 million self-identifying Sikhs globally, of differing socio-economic groups, speaking a variety of languages and pursuing a multitude of practices and views. Large proportions of them reside in the states of Panjab and Haryana in India, and across UK, Canada and USA but their presence now is in every continent except perhaps the extreme southern continent of Antarctica. One thing that many if not all come together on since at least the early twentieth century is the holiness attributed to Amritsar’s Golden Temple also known as the Harmandir Sahib. Pilgrim presence literally marks the marble on and around the walkway (parkrama) around this central shrine situated in the sacred waters of the sarovar.

Donor engravings are often found on places seen as auspicious (mangala) throughout India for the establishment, building, renovation and maintenance of a holy shrine or other prominent buildings. The engravings in and around the Harmandir Sahib number in their thousands with the largest in cartouches around the main entrances. Others are down the flight of steps, on the lower parts of the wall and ground around the edges of the parkrama; around the Darshani Deori that leads to the causeway to the main shrine including even on the historic marble stairway in the shrine’s interior (Figure 2); around the Dukh Bhanjani Beri next to which Guru Arjan Dev (1563-1606) used to sit, a place known as Thara Sahib (Figure 3); and around Baba Deep Singh’s (1682-1757) shrine in honour of his wisdom, martial and miraculous associations (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Darshani Deori that leads to the causeway to sanctum sanctorum in Harmandir Sahib complex

Figure 3: Thara Sahib next to the Dukh Bhanjani Beri where Guru Arjan Dev used to sit

Figure 4.: Baba Deep Singh’s shrine in Harmandir Sahib complex

Marble Markings

The most prominent engravings are by army battalions from the 1950s and 1960s around both northeastern and southwestern Clock Tower entrances. These are in commemoration of battles, the deaths of soldiers conceived as martyrs to the nation, with respect and reverence to their stationing in Amritsar, or in celebration of major festivals such as Nanak Jayanti, the birthday of the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak Dev (1469-1539). There are also memorial plaques of historical events and engravings of soldiers who died fighting World Wars I and II such as one ‘In the sacred memory of Shaheed Sub Gainda Singh who sacrificed his life during 1st World War at Basra in Jan 1918 and Mata Atar Kaur [sic].’ One engraving on the side of the Akal Takht Sahib entrance in its list of awards gained by all ranks in Panjab (Patiala) starts from 1705-1999. The Second Battalion Sikh Light Infantry have a large engraving as a ‘roll of honour’ for ‘brave soldiers who laid their life for the country’ starting with battles from 1948, 1949-50 against Pakistan with a massive increase of deaths in the war against China in 1962, followed by other battles or wars with Pakistan in 1965, 1971, 1991, 1999 and the military ‘standoff’ in 2002.

The other inscriptions are by ordinary individuals from a variety of backgrounds. There is one in both Panjabi and English from Mehar Singh Chadha ‘of Iran’ and Ishar Singh Chadha who ‘imbued with deep devotion & inspiration to under take “sewa” (selfless service) of these two burgies out of “daswandh” 15-2-1950 [sic]’ around the south western entrance. The ‘burgies’ are the structures flanking the end of the steps and dasvandh literally means ‘tenth part’ (Figure 5).

Figure 5: 'Burgies' around one of the entrances to the Harmandir Sahib complex

It is explained as follows:

‘The principle of Dasvandh is that if you give to the Infinite, Infinity, in turn, will give back to you. It is a spiritual practice through which you build trust in the ability of the Infinite to respond to the flow of love and energy that you give. This energy then expands tenfold and flows back to you in abundance.' - Sikh Dharma International website

Although the principle of vandh chankna or sharing your hard-earned income was there from the time of Guru Nanak Dev, it was formalised as a tenth of one’s income to the community under Guru Arjan Dev when finances were running dry for the construction of the Harmandir Sahib and the provision of a communal kitchen or langar for visitors at the site.

The earliest extant engravings appear to be from the colonial era with some clearly written with dates from the 1930s on a raised platform near the Dukh Bhanjani Ber. They are inscribed in English in the Roman script and the Urdu script, the standard in educational institutions in pre-independence Panjab (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Inscriptions in Urdu and Roman scripts near the Dukh Bhanjani Beri in Harmandir Sahib complex

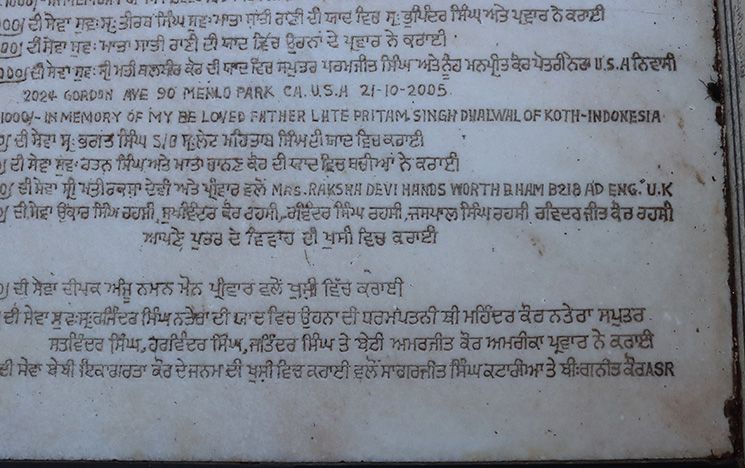

After the 1950s, Panjabi in the Gurmukhi script began to dominate in the engravings with a scattering of English and only on occasion, Hindi in the Devanagari script now the national language of independent India. Occasionally the votive message is both in Gurmukhi and English so that all generations of the family in India and overseas can read it as for: ‘1100…Mrs Raksha Devi Hands Worth Bham [Handsworth, Birmingham] B218 AD Eng. UK [sic].’

Figure 7: Votive messages in Gurmukhi and Roman scripts, one of which is from a donor in Birmingham

In the Midst of Violence

Codenamed Operation Bluestar, a government-backed military attack in 1984 to oust militants caused much damage and deaths including those of civilians who were visiting Harmandir Sahib at the time to commemorate the martyrdom in 1606 of the fifth guru, Guru Arjan Dev. 493 civilians are claimed to have died by the central government in the violence as opposed to 741 by the Panjab gurdwara authority, Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), who have recorded the names of men, women and children on the corridor of the Central Sikh Museum on the north-eastern side of the complex. After the assassination of the prime minister Indira Gandhi on October 31st of that year by her Sikh bodyguards, the Congress Party orchestrated mass murder, pillage and rape of Sikhs in Delhi and other cities. The series of events both shocked and consolidated many people in India and around the world, such that they took to protests against human rights violations – civilian deaths, illegal custody, torture and disappearances - while seeking to make amends for any physical damage caused in Amritsar itself.

Figure 8: Akal Takht Sahib that was rebuilt after its destruction in 1984 in the Operation Bluestar (para)military attack

To curb such international support, the Congress-led government barred international communities from donating directly to the Harmandir Sahib from 1984, an act that was only repealed in 2020 owing to economic strains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, supporters had been sending their donations indirectly through their networks and personally when they made visits to Amritsar. The 1980s was a dangerous and volatile time for many to travel to Panjab including Non-Resident Indians (NRI) – the generic name given to all diasporic Indians no matter where they reside or their citizenship.

Those donations from the mid-1980s epitomise a driving impulse to rebuild the Harmandir Sahib complex in international kar seva (selfless service). The inscriptions include references to commemoration of shahidi, to donate to the rebuilding of the Harmandir Sahib complex and the city of Amritsar, and to mark the exoneration of charges as mentioned in one with ‘Surjit Singh S/O [son of] Ganesha Singh Guard, N. RLY Chowk Baba Sahib Gali Gujran Amritsar in memory of acquittal of cases [sic].’ Donations went towards the rebuilding of the Akal Takht Sahib, the repair of the Harmandir Sahib and parkrama that too was destroyed by bullets, grenades and tank fire, and the desilting of the sarovar in October 1984 that was viewed as polluted by the bloody massacre.

Figure 9: Damaged areas of the Harmandir Sahib complex as a record of the Operation Bluestar (para)military attack in 1984

There are many engravings that are in memory of those who have passed away to svaragvasi written either in Gurmukhi or translated into ‘heavenly abode’ in the English from the mid-1980s. A couple of them expressly indicate that their donation is to rebuild the parkrama or complex. One donation of 201 rupees is in memory of a ‘brother’ Kabla Singh and others who was martyred from the ‘Building Divisions Staff’ of the SGPC. Some are written in a generic sense to do seva for the city of Amritsar after the damage in the wake of the 1984 military storming.

Global Panjabis

In the mid-1990s, when the volatile political situation subsided, more and more diasporic Panjabis began to visit the Harmandir Sahib complex. The 1990s was also a decade that saw neoliberal deregulation of the markets making travel to the state more consumer friendly with the operation of flights from Delhi to Amritsar in north Panjab. Correspondingly, the inscriptions indicate an expanding circle of donors located outside India, many of whom were engraved by construction staff hired by the SGPC as opposed to specialist marble engravers. These global Panjabis include the legacies of older diasporas from Singapore (sometimes spelt Singapur), Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), Bangkok (sometimes spelt Bankok, Thailand), Koth (Indonesia), Tehran (Iran), Dubai (United Arab Emirates), Johannesburg (South Africa), Nairobi (Kenya), Arusha (Tanzania) and Kampala (Uganda); and later diasporas from UK, Spain (Barcelona), Austria, Australia (Adelaide, Sydney), USA (California, Texas, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Newark, Virginia, Iowa City, Minneapolis, Kentucky) and Canada (Vancouver, Toronto, Calgary, Ontario) – the latter is also indicated in the two large digital boards that relay the verses of the holy scriptures, Shri Guru Granth Sahib, translated into colloquial Panjabi and English that was donated by Panjabis based in Canada.

Figure 10: Digital displays representing verses of the holy scriptures, Shri Guru Granth Sahib

In terms of donors from UK, there are inscriptions from people based in Birmingham, Solihull, Smethwick, Bilston, Walsall, Willenhall, London, Romford, Hayes, Hounslow, South Ruislip, Cranford, Luton, Dartford, Gravesend, Southampton, Manchester, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dundee. For instance, one in the Gurmukhi script states: ‘400 Rs seva from Mr Piara Singh Mistri Jadial from Anglesey Street Birmingham 18 (UK).’ Another indicates a larger sum and is put in a cartouche on the side of one pillar: ’150000 seva from Mrs Barjinder Singh Thiara son Mr Harbans Singh Thiara Birmingham (U.K.).’

After the tortured memory of the military attack on the Harmandir Sahib complex subsided somewhat, celebratory events resumed from the 2000s as with marking the occasion of birthdays, retirements, or wedding anniversaries as with one in Roman script on the inside of a pillar:

‘With the blessings of Guru Ramdass Ji we Gursharn Singh Lakra & Mrs Kalwant Kaur Lakra resident of Tameton Close, Luton Beds England LU2 8UX offer our prayers with thanks to the guru’s feet with humble amount of one lakh (100000) rupees on the occasion of our golden anniversary occurred on 21-4-2001.’

The celebration of birth and wedding announcements and anniversaries are modern phenomena that were not practiced historically. Expressive language is also a latter-day phenomenon. One from Britain shows a blend of Sikh and Christian ideas:

‘Ik Onkar Sat Guru Parsad S. Jasbir Singh Gill (9th MARCH 1964-11th FEB 2010) s/o [son of] S. Gurdev Singh & Sardrani Jeet Kaur from all of the family “Rest in peace” You will always be in our hearts. By His Grace may your soul have peace and tranquillity. Solihull West Midlands U.K.’

Such lyrical dedications are rare. Some inscriptions simply show seva donated when gaining a first job and/or of first salary. Others request generic blessings with health, peace and a positive attitude - ‘sukh shanti ate chardi kala’ - as is often recited in ardas (prayer or petition). Others thank God for recovering after illness.

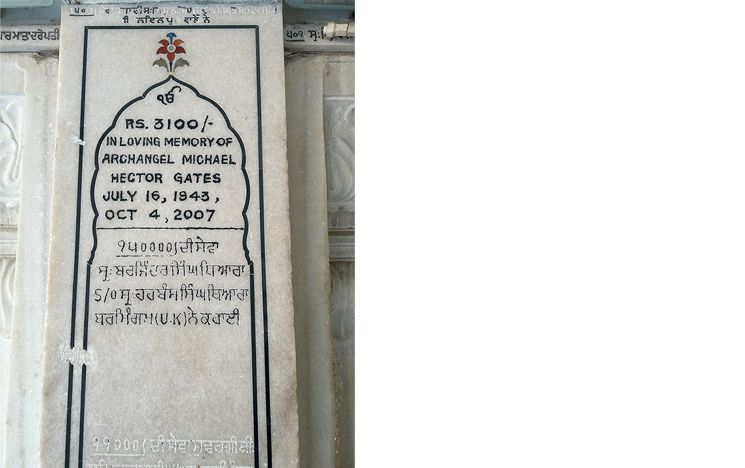

Most donors are of Sikh names, although there are occasional ones that are professedly Hindu and idiosyncratic examples of Anglophonic names where they have either (i) donated in their own name as they had developed a deep respect for the place; (ii) married other Panjabi people; or (iii) they had simply anglicised their names. An example of the former is an engraving topped with pietra dura work. It is the only one that is idiosyncratically dedicated to a Christian icon, Archangel Michael, in memory of a loved one: ‘Ik onkar Rs. 31000/- in Loving Memory of Archangel Michael Hector Gates July 16, 1943, Oct 4, 2007.’

Figure 11: Pillar engraving topped with inscriptions about Hector Gates and, underneath in Gurmukhi, Barjinder Singh from Birmingham

According to my interlocutors, he is most likely to be a British army officer, born in India, or family members who visited the Harmandir Sahib and requested the engraving out of a sense of his and/or their spiritual conviction or connection to the place.

For (ii), an example is a Panjabi man who married an English woman: ‘RS 2100/1 presented Bilson (1991) S/O S. Gurmukh Singh Chhatwal-Margaret (wife) Sonia (daughter) Devinder (son) …Vineyard Hill Road, Wimbledon, London (UK).’ For (iii), an example is: ‘Rs 200/-In loving memory of Charanjit S. of Seattle, USA Father, Friend, And Inspiration. Daughter Jasjit (Jessica) Kaur.’ Just as with the foundation story of the building of the Harmandir Sahib - that its four doors were to be open to all castes and creeds - so with the inscriptions that there be no bar against who can express their donations on marble.

Marble Murmurings

By the 2010s, whilst donations for the Harmandir Sahib increased from across Panjab, India and overseas, donor engravings in the complex fell into decline largely because the purity of unstained marble began to be seen as more aesthetically pleasing for a holy place. Moreover, humility rather than the pride attached to names was to be valued. As one sevadar (caretaker) explained:

‘If you put someone’s name on it, on the one hand, it creates pride. On the other, it creates disagreement as others say that they want their name there and so on and so on. It is best not to have them.’

Another stated:

‘It’s like ardas. But if you have ardas engraved in stone then you show your kids and so on. It gets stuck in your mind that “this is my stone”. It’s like buying property, making a mark on the place. One foot by one foot – that becomes mine. It’s like buying a piece of the moon!’

The moon has its place, and that is in the sky.

Figure 12: Harmandir Sahib on a moonlit night

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to Sandeep Singh, Shivcharan Singh, Manu Singh, Dipti, Virinder Kalra, Gagan Chhina, Tahira Khan, Akbar Khan, and Prabhjit Singh for their discussions. Thanks also to Muhammad Qasim Yaqoob for assistance with translating inscriptions in the Urdu script. The essay was completed during the ‘Pilgrimonics’ project that continued research on the subject from Spring 2022 when I was a Research Fellow in the framework of the Kolleg-Forschungsgruppe ‘Religion and Urbanity: Reciprocal Formations’ at the Max Weber Centre of the University of Erfurt (FOR 2779, German Science Foundation) led by Susanne Rau and Jörg Rüpke.