Beyond Religion, Beyond Pilgrimage

Raminder Kaur

One book that I found very inspiring while doing my fieldwork in India and Pakistan on ‘Pilgrimonics’ - a neologism for pilgrimage and economics and/or circuits of exchange - is Beyond Religion in India and Pakistan: Gender and Caste, Borders and Boundaries by Virinder S. Kalra and Navtej K. Purewal (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020). Informed by extensive fieldwork in the neighbouring South Asian countries - itself a major feat when relations between the two can be so fraught – the authors note how they ‘witnessed meticulous policing of the formal observation of religious boundaries and identities;’ but simultaneously, ‘a tremendous amount of spiritual openness by way of an underlying perseverance and desire to sustain practices which did not necessarily “fit” in accordance with formal religion’ (p.5). The authors trace these dynamics of openness and closure to demonstrate how borders – whether they be geopolitical, social, religious, or political imbued with religious nationalisms of kind - are in constant motion (p.5). Accordingly, their field sites are not hemmed in by geophysical boundaries – spanning shrines of all kinds across the Panjab province of Pakistan and the Panjab state of India, and extending to sites in the state of Himachal Pradesh while alluding to those in Sindh and Kashmir by way of the literature - academic, poetic and spiritual. This endeavour includes noting synergies with the oeuvre of spiritual-poets from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, especially Waris Shah, Bulleh Shah, Piro, and the gurus (teachers) Guru Nanak and Guru Arjan that ‘puncture the hegemonic forces of dominant caste ideology and patriarchy in a way that connected to the concerns of women and dalits’ (p.7) – the latter term meaning ‘broken’ and referring to marginalised castes previously known as Untouchables or Harijans.

The authors’ main objective is even more important when considering the rise of exclusions in a context where violence accompanies caste exploitation, patriarchy, and misogyny. Their approach recognises ‘boundary-making and -breaking processes as coterminous’ (p.6). Instead of taking religious identifications for granted, they note how they operate in relation to the politics of inclusion and exclusion, particularly regarding caste and gender. Effectively religious identifications such as Sikh, Hindu and Muslim operate according to dominant metanarratives imbued by high-status patriarchal logics.

When religious identities framed in singular terms have such global sway, it is indeed difficult to not use them, let alone think outside of their bordering logics born out of colonial modernity. Still, following theorists such as Antonio Gramsci, James Scott and Michel de Certeau, the authors seek to look at counter-narratives and the ruptures and cervices extant in everyday practices of devotion and piety around shrines ‘not definable by dominant markers of religion or religious identity’ (p.11). They maintain: ‘In many ways, this is not a book about religion, but instead is a book about religion-making and religion-breaking as a dynamic process of authority and its inversions and subversions’ (p.12). Altogether the authors provide an impressive, multi-layered account of ‘border crossings’ to open ‘a conversation about the permeability of borders, the subjectivity of the people who navigate them and the acts within which they articulate agency’ (p.2).

The book made me think about how we can begin to conceive of pilgrimage beyond dominant religious markers. It is true that there is a need to move beyond pilgrimage so as we do not simply identify it as accompanied by particular terms and destinations for particular groups of people. This is not simply to argue for its overlaps with the more expansive term, tourism, as the scholarship has explored. Rather to consider everyday practices in preparation for, to, and at those destinations, while considering social inclusion and exclusion, openness and closure, all along the way. This approach also begs the questions of what is pilgrimage, what other ways are there of conceiving of its parameters and the aspirations and experiences of those who go on such journeys, and how can we think about doing and writing ethnographies that go beyond pilgrimage, and indeed beyond pilgrimonics?

Kalra and Purewal’s book gives a sophisticated articulation of what I often came across in fieldwork in South Asia where it seemed that there was a melange of practices that could not be determined as Sikh, Hindu, Muslim or Buddhist (see my blogs, ‘Yatra’ and ‘Tapestries’). Coming from diasporic locations in the UK and USA, Kalra and Purewal’s observe that religious identities are more rigid ‘eternal and absolute’ (p.1) in the diaspora but appear to dissolve when in the South Asian context. Indeed, I noted this for diasporic visitors when they made frequent trips to shrines that might otherwise be seen as of Other religions of South Asia. When I accompanied an organised tour (yatra) by the Birmingham-based historian, poet and author, Ranjit Singh Rana, we visited the Mian Mir tomb in Lahore in February 2023 who was decreed a Sufi (Muslim) saint (pir, Figure 1). I too noted gendered exclusions, but while I was not permitted to go into the inner sanctum, I was permitted to see the tomb from the doorway and the caretakers offered to take my smartphone around it to video it instead. These were privileges accorded to diasporic woman, and not local woman from the region – although how it affects those who are of higher class accorded ‘VIP status’ is something else to query.

tomb Figure 1: Mian Mir's (dargah) in Lahore, West Panjab, Pakistan

tomb Figure 1: Mian Mir's (dargah) in Lahore, West Panjab, Pakistan

Throughout the yatra, we came across many self-identifying Muslims who were ardent believers of Guru Nanak, accorded the mantle of the founder of Sikhism, and whose place of birth and death are now circumscribed by the border of Pakistan. Referred to as ‘Baba Nanak’, he was revered across socio-religious communities. Observed also as far as Dharamshala in the regions of Himachal Pradesh, Ladakh and Tibet, Buddhists referred to Guru Nanak as a reincarnation of Guru Rinpoche. Both gurus had travelled from India to spread their wisdom, and both are associated with popular stories about miraculous powers. Such observations characterise what could be called a ‘New Age Sikhism’ as precedents like this have escaped analysis, where the New Age cuts against the fixity of the latter, and practices associated with Sikhism infuse the former with another valency that is rooted yet open. This emergence has come out of a particular consonance of middle-classness, travel possibilities, egalitarianism, spiritual curiosity and the international appeal of the Dalai Lama, a spiritual celebrity in his own rights.

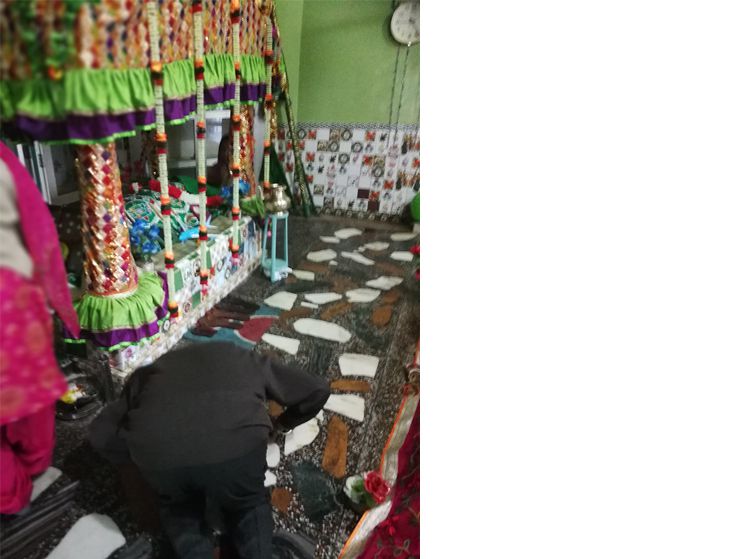

Similarly, in other contexts, there is continuous veneration of (Hindu) sants in the making of the Sikh holy scripture, Shri Guru Granth Sahib, as evident in one of the Panj Takhts (Seats of Authority) in Nanded, Maharashtra, that forms parts of diasporic yatra tours in India. The heteropraxy of everyday devotion was also evidenced when members of the Birmingham diaspora returned to their ancestral village to join celebrations at their local shrine associated with a pir in East Panjab (Figure 2). Similarly stories about the ongoing maintenance and worship of abandoned graves of pir crossed religious demarcations and practices, when their original caretakers ran to the newly formed nation of Pakistan on declaration of partition in 1947, one of whom who came to live in the UK and study medicine at the University of Birmingham in the 1950s. The Conversation website

Figure 2: Inside the shrine for Mangu Shah pir in Sahni village, East Panjab

A key take-away of Kalra and Purewal’s book is the need to decolonise religious studies in South Asia and to unsettle the hegemonies within the study of religion and society influenced by Eurocentric and colonial registers. As the authors argue in Chapter 2 on ‘conceptual pilgrimage’, there is a need to move away from ‘border-thinking’, particularly pertinent now at a time of religious statism and extremism. Instead, they maintain that: ‘In line with postcolonial approaches, we address religion as a question or series of questions rather than a normative classification or set of categories’ (p.20). As they lyrically write: ‘If religion was the opium of the people in Marx’s time, we argue that religion now is the amphetamine of contemporary times with violent, rather than sedating, effects’ (pp.18-19).

Informed by long-term fieldwork including ‘ethnography, semi-structured interviews, devotee surveys at shrines, textual/inter-textual analysis and photography, and video recording of practices and performance at melas [fairs] and shrines’ (p.7), the authors provide a rich, multi-layered account of shrine practices, highlighting avenues of openness and inclusion amongst the closing doors of dominant narratives of closure and exclusion. Considering what ‘people do’ rather than what ‘they say they do’ is central to their lens (p.37). They note that: ‘Shrines and popular devotion do not directly impinge upon the casteist and sexist social structure of Punjab but do provide a space for women and dalits to express agency, rather than being acted upon, even if in a highly circumscribed way’ (p.28).

With a transhistorical approach but always with an eye to the contemporary, Chapter 3 explores ‘the role of the Pir, Sant, Baba, Faqir, Bhagat, Sheikh, Saain and Mahapursh, all labels for what we conflate in the English term “spiritual figure” ’ (p.39). Whatever their religion, practices converge by virtue of ‘the rituals of obeisance and the demands that devotees place on these spiritual figures’ (p.39) emerging ‘out of a common moral and textual spiritual landscape’ (p.43). Three areas characterise supplications that people make: ‘Wealth (personal and collective), health (physical and mental) and spiritual wellbeing (in relation to jinns/bad spirits and bhooth/ghosts)’ (p.58). As I too observed among diasporic visitors, while the devotee may make a vow, change behaviour, or undertake a penance, in return, they would donate finance and/or food that itself would be blessed.

Chapter 4 accounts for the ‘sacred spaces’ of the ‘common shrine’, be it a mandir associated with Hinduism, gurdwara with Sikhism, or the Islamic dargah or masjid. Such shrines take on more prominence and intensity at the time of festivals whether it be respectively utsav, gurpurab, or urs, captured collectively in the term mela for fair. It is at such times that key rituals of marriage, communal distribution of food, petitioning, and other forms of exchange and celebration occur (p.9). Crucially, the authors argue against what they call ‘a methodological religious essentialism, akin to methodological nationalism’ (p.79).

Chapter 5 considers ‘openness and closure as encapsulated by the boundaries of religion, caste and gender’ (p.84) with case studies of female spiritual leaders and organisations, Brahma Kumari and Al-Huda, that defy gender orthodoxy while adhering to normative religious traditions. The authors also note how masculinised high-status bordering logics have made the Harmandir Sahib and Durgiana Mandir in the city of Amritsar iconic sites for worship but relegated the Valmiki site associated with marginalised Dalits at Ram Tirat to the edges of sacred geographies (p.99). This is despite the fact that statues of Valmiki are within the Durgiana Mandir complex, which they argue ‘is a strategic incorporation which simultaneously includes while it excludes’ (p.100). The question arises as to what evidence there is for such conclusions, and how does one account for the recent renovation of Ram Tirat by the high-caste Sikh dominated political party, Akali Dal, in 2018? Perhaps this multi-million-pound investment was before the authors’ main period of fieldwork, but there are some points of resonance in Chapter 6 about the role of the postcolonial state in perpetuating the framework of colonial modernity especially when it comes to electoral considerations at a time of rising high-caste Hindu nationalism epitomised by the Bhartiya Janata Party.

Particularly pertinent to my pilgrimonic lens, Kalra and Purewal list several supplications that they came across. Whether it be the Hindu aarti, Sikh ardas, or the Islamic dua, they were remarkably similar. Here are a few examples:

‘In the name of the almighty, thanks for bringing us together in the presence of your exalted beloved [name of pir/guru]. We are here to ask for your blessings and to bring your grace onto us poor sinners/unknowing. Ameen/Waheguru/ Ram

Please give blessings to Bhola for his donation of 50Rs [rupees] to the langar [communal food].

Praise and thanks for the birth of Pappu to Bibi Sheeda after taking a mannat [prayer/wish] 5 years ago’ (p.121).

Another that I noted in Amritsar was blessings for those who were applying for a visa – often to Canada – and when attained, to ask for protection for those going abroad on visas. Kalra and Purewal conclude that the structure of such appeals was common: ‘an opening invocation followed by praise of the shrine’s spiritual resident, a list of those who have donated money and contributed to the langar…, followed by those who desire a public petitioning of their needs. It is this recognition of material benefit by the devotee, the public and the people that breathes life into the brick and marble of the shrine’ (p.121).

Such common practices all operate under the closure of religiously marked frames that exclude women from mosques and Dalits from ‘the inner sanctorum of many mandirs’ (p.122). Gurdwara whilst in practice open to all genders, castes and creeds show hierarchical exclusions when it comes to management and particular practices such as the musical performance of kirtan by women in the Harmandir Sahib, although this is not stipulated for other gurdwara. The authors do not consider notable moves on this front, however: one being that the head of the authoritative Akal Takht from 2018-2023, Giani Harpreet Singh, is a Dalit. Another is that key female figures have mobilised for equitable gender representation including for women to perform in the Harmandir Sahib, one that has gained a following with many of my interlocutors saying it is only a matter of time or another generation when this will be possible.

Chapter 6 moves on to discuss sacred shrines, figures, and movements in relation to the state. To do so, the authors adopt Persian terms such as ‘sarkar (senior official), darbar (court) and vilayet (jurisdiction) that entered Punjab via the Delhi Sultanate and Moghul empire’ to ‘demonstrate how various domains of authority have been constructed around different seats/bodies, settings and positions of power’ (p.134). Here they make the significant point about patronage and income from endowments and devotees that are major factors in the popularity of shrines. This is often associated with charitable extensions as with hospitals, dispensaries, libraries, guest houses, schools and colleges that extend to supporting marginalised groups. However, the authors maintain that such religious philanthropy is of a tokenistic nature that does not undermine the otherwise patriarchal casteist structures at large.

The final chapter on ‘devotion, hegemony and resistance at the margins’ does an excellent job of summarising the main points, noting how the book fulfils a lacuna in extant scholarship, which has been preoccupied with how the colonial context created the religious categories of Sikh, Muslim, and Hindu, but not as to ‘their continuity, maintenance and enhancement into the twenty-first century’ (p.171). They also allude to new developments in digital interfaces along with a remarkable anecdote of the materiality of virtuality when visiting a historic gurdwara near Islamabad, Panja Sahib, associated with Guru Nanak. The authors’ companion, whose family had converted to Islam, video-called his friend in Chandigarh across the border ‘to give him “darshan” of the gurdwara. The squeals of joy and repetition of “Waheguru” [God is wondrous] coming through the mobile phone as we wandered around was indicative of a border crossing of a different type from viewing one of the many video documentaries made about Panja Sahib’ (p.173).

Altogether, there are many signs of impressive scholarship and fieldwork conducted in tandem by two authors across two nations. It would have been interesting to expand the focus on gender and caste to the ‘three-dimensional matrix of caste, class and gender’ (p136) as they note in Chapter 6 to the other chapters too. Even if class comes with a capitalist framework, it also has its proto-class or semi-class dimensions when considered in terms of financial exchange that led to shrine formations, the socio-political prominence of spiritual leaders or figures, the rise of propertied territory, shrine popularity and their location on mercantile routes that come with increased donations, and the further exclusion of gendered identities moving away from gender complementarity to a more marked hierarchical segregation in capitalist formations.

Even though I found the book an outstanding thesis against border-thinking logics, I found it extremely difficult to not use religious categories even if I disagreed with their fixity. Terms such as Sikh, Hindu and Muslim have become convenient shorthand for a range of complexities both inherent in the terms and their social contexts. The authors fall short of offering alternative framings, other than a constant interrogation of categorical closures informed by a counter-hegemonic approach. This I suppose is where the limit of our thinking lies.