Kirtan: The Soaring Sounds of Sacrality

Prabhjit Singh and Raminder Kaur

Ask any person who goes to the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple), the second they walk through the marble entrances and catch their first glimpse of the golden structure shimmering in the sapphire blue sarovar (sacred water pool), there is a deep sense of awe. The reality of this encounter never quite meets its reproduction in photograph or film (Figure 1). Added to this is the place’s immersion in the sounds of spirituality coming out through scattered speakers around the walkway from the musicians and singers (ragi) performing in the sanctity of its innermost shrine.

Figure 1: Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar

One visitor echoed this sentiment of awesome astonishment, along with a sense of the elevation of place when she walked through the archway:

‘When you enter this place, it feels like heaven. It is so different from the hustle and bustle everywhere else. The holy sounds of the shabads (holy Words or sacred songs) surround you. And they lift you to another plane. The kirtan (spiritual singing) here is very different to what we regularly hear in our gurdwaras in England.’

The emphasis in the Harmandir Sahib is to adhere to the Sikh guru’s instructions for kirtan (devotional music) as much as possible. This is one of its distinguishing factors when compared to kirtan performed in other gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship) in India or across its diaspora who may add other styles and striking instruments including the dholak drum, chumti tongs with jingles, or even compose their own verses to the music. This is also one reason why hazuri ragi - those singer-musicians who are of superior authority based in the Harmandir Sahib - are revered everywhere in the global Sikh-scape such that their group (jatha) often go on global kirtan tours (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Kirtan groups from India in England

While these ragi may command cash donations in other gurdwaras as they sing their mellifluous music, they do not do this in this most revered of Sikh shrines even while donations are made in front of the SGGS as devotee make obeisance.

The badge of being a hazuri ragi at this central place of the Harmandir Sahib is enough of a credit to any kirtan career. This is a performance that is akin to Marcel Mauss’s work on the ‘pure gift’ – one that is not sullied with cash and performed with pure devotion. Here, they aspire to the pristine purity of the times of the Sikh gurus.

The original idea is that in this world each living being has its own sound. This sound is called dhun. The first guru, Guru Nanak Dev (1469-1539), was attuned to this and promoted it across his followers:

ਧੁਨਿ ਮਹਿ ਧਿਆਨੁ ਧਿਆਨ ਮਹਿ ਜਾਨਿਆ ਗੁਰਮੁਖਿ ਅਕਥ ਕਹਾਨੀ ॥੩॥

The meditation is in the music, and knowledge is in meditation.

Become Gurmukh, and speak the Unspoken Speech. ||3||

(Sri Guru Granth Sahib, p.879)

There were many types of sangeet (music) at the time of Guru Nanak Dev in the fifteenth century. Devotional music was popular in the bhakti mode – that is, spiritual song that drew upon the idea of a couple in divine love (premi premika) as in Krishan raslila. But Guru Nanak Dev introduced the qualities of Rab (God) as the invisible yet universal focus of this devotional music. This approach is called gurmat sangeet – literally meaning music to the Words of the divine – and through gurmat sangeet any person could get to the heavenly mansion of God. Kirtan provided a way to a universal Creator that other religious routes could not then provide – as with Brahmanical religions or those that required bodily skills like hatha yoga or penance (tapasya).

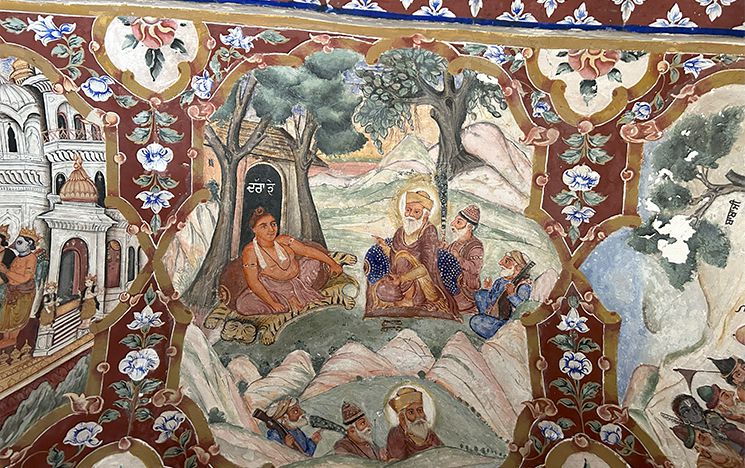

Guru Nanak Dev made shabad his guru (teacher), implying that in the movement from ignorance (gu-) to light where darkness is dispelled (-ru), we cannot speak without God. Along with Bhai Mardana, the guru’s disciple and rabab player from a Muslim background, they modified the shabad and gave it the roop (face) of kirtan (Figure 3). Compositions were brought together in notational groups called raga with specific affective qualities or tastes (rasa) borrowed in simplified form from classical music. In kirtan, the Word rather than the music took precedent. In praise of God, the style of the singing of people who sang these ragi were called raagi, and the musical-song performance, kirtan – a word invented to describe parmatama di kirti gana, to praise whatever God does.

Figure 3: Mural of Guru Nanak Dev and Bhai Mardana in Gurdwara Baba Atal, Amritsar

The Sikh gurus became experts in kirtan, and there are many historical incidents where they taught it to their followers (sangat). The message of the fifth guru, Guru Arjan Dev (1563-1606), was:

ਕਲਜੁਗ ਮਹਿ ਕੀਰਤਨੁ ਪਰਧਾਨਾ ॥

In this Dark Age of Kali Yuga,

Kirtan for the Lord’s praises are most sublime and exalted.

ਗੁਰਮੁਖਿ ਜਪੀਐ ਲਾਇ ਧਿਆਨਾ ॥

Become Gurmukh [like the Guru’s persona], chant and focus your meditation.

ਆਪਿ ਤਰੈ ਸਗਲੇ ਕੁਲ ਤਾਰੇ ਹਰਿ ਦਰਗਹ ਪਤਿ ਸਿਉ ਜਾਇਦਾ ॥੬॥

You shall save yourself and all your generations as well.

You shall go to the Court of the Lord with honour II 6 II (SGGS p.1075)

Guru Arjun Dev compiled the holy scriptures in raga styles with the intention that the words be sung such that blissful union with the divine could be attained. As he stated:

ਰਾਗ ਨਾਦ ਸਬਦਿ ਸੋਹਣੇ ਜਾ ਲਾਗੈ ਸਹਜਿ ਧਿਆਨੁ ॥

Those Ragas which are not in the Sound-current of the Naad [sound vibrations]

– by these, the Lord’s Will cannot be understood. (SGGS, p.849)

The Sri Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS) provides instructions on how to sing the kirtan in a manner that was accessible to ordinary people familiar with folk songs as prevalent in celebrations (sohila), weddings (ghoriya), and funerals (aalanya). Apart from ੴ - Ik Onkar (There is Only one Creator) - written at the top of each verse, the house (ghar) of raga is also included in the title of verse. In the SGGS there are 31 main raga that are divided into 62 including mishrat or mixed modes. Every raga has its own form, content, time, season and other qualities of nature. Each creates a special affect intact with a series of notational rules for the music. Examples include the rasa of gallantry (vir), peace (shanti), happiness (suhi), sweetness (kalyan), sadness (todi), compassion (karuna), and renunciation (vairag).

These raga are combined with instructions as to rhythm, where depth and the steadiness of speed is emphasised in the SGGS such that the shabad has time to embed itself in the body, mind and spirit. Sant Kabir stated:

ਹਰਿ ਕਾ ਬਿਲੋਵਨਾ ਬਿਲੋਵਹੁ ਮੇਰੇ ਭਾਈ ॥

Churn the churn of the Lord, O my Siblings of Destiny.

ਸਹਜਿ ਬਿਲੋਵਹੁ ਜੈਸੇ ਤਤੁ ਨ ਜਾਈ ॥੧॥

Churn it steadily so that the essence of the butter is not lost (SGGS, p. 478)

Such kirtan was decreed useful to present lives as well as afterlives (parlok):

ਗਉੜੀ ਮਹਲਾ ੫ ॥ ਗੁਰ ਸੇਵਾ ਤੇ ਨਾਮੇ ਲਾਗਾ ॥

Serving the Guru, one is committed to the Naam, the Name of the Lord.

ਤਿਸ ਕਉ ਮਿਲਿਆ ਜਿਸੁ ਮਸਤਕਿ ਭਾਗਾ ॥

It is received only by those who have such good destiny inscribed upon their foreheads.

ਤਿਸ ਕੈ ਹਿਰਦੈ ਰਵਿਆ ਸੋਇ ॥

The Lord dwells within their hearts.

ਮਨੁ ਤਨੁ ਸੀਤਲੁ ਨਿਹਚਲੁ ਹੋਇ ॥੧॥

Their minds and bodies become peaceful and stable. ||1||

ਐਸਾ ਕੀਰਤਨੁ ਕਰਿ ਮਨ ਮੇਰੇ ॥

O my mind, sing such Praises of the Lord,

ਈਹਾ ਊਹਾ ਜੋ ਕਾਮਿ ਤੇਰੈ ॥੧॥

which shall be of use to you here and hereafter. ||1|| (SGGS, p.693)

Through reciting naam (Name) and singing kirtan, all problems and fears are vanquished, and the restless mind is comforted. This is the kind of kirtan prioritised in the Harmandir Sahib.

In recent decades, however, ‘light tunes’ have also emerged. Influenced by modern popular music, these depart from the rules of raga to emphasise a repetitive melody. Even though the gurus did not have the harmonium organ at the time - an instrument that was introduced to India from Germany in the late nineteenth century - they invented instruments that occasionally can be heard in the Harmandir Sahib to this day. Guru Arjan Dev invented the saranda – a stringed musical instrument on the basis of the sarangi with a sweeter sound (madhur saaj). The tenth guru, Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708), invented another stringed musical instrument, taus, that some historians credit to the sixth guru, Guru Hargobind Singh (1595-1644).

Whereas in most other gurdwara, devotees get up to donate to the raagi in appreciation, here in the main shrine of the Harmandir Sahib, they are only encouraged to give through their heart. To perform in the Harmandir Sahib itself is the zenith of musical achievement, and to hear it live is itself a spiritual prize. The only ragi who are offered cash donations in the Harmandir Sahib complex are ordinary ones who perform a ritualistic function after the SGGS is read in akhand path in the hundred or so smaller shrines surrounding the two axiomatic buildings– the Harmandir Sahib as the centre of spiritual power (piri) and the Akal Takht Sahib opposite it, the centre of temporal power (miri).

Without the melodious music of kirtan, there is little atmosphere at the Harmandir Sahib complex; and without atmosphere there is next to nothing.