Of Loud Speech and Silences Louder Still

Vrishali

‘Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it.’

Syme to Winston on the ‘beauty’ of the totalitarian state (‘Big Brother’) in George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984.

Although I have some recollection of the past, my memories from childhood are quite foggy overall - as, I believe, is the case with many. We live in a world full of social media distractions and remembering is a hard and compulsive act to put ourself through when even personal narratives come readily served on ChatGPT with a semblance of the real and a garnish of the lyrical.

On one rare occasion when my mother had decided to reward me with a cup of adult beverage, chai, I remember sitting in our living room on a rainy day and having a ‘nearly adult’ conversation with her as we looked on to the pitter-patter of tiny rain drops drumming upon the windowpane. The electric power was out - as was usual for most monsoon evenings of our small, sleepy town in Bihar, and she was relating to me a strange story from her own childhood.

She told me about how sardars (turbaned Sikhs) were hunted down in the capital of Bihar, Patna. They had to cut off their long hair and shave their long beards in the aftermath of the assassination of the then prime minister, Indira Gandhi, by her two Sikh bodyguards, just in order to save themselves. ‘The Sikhs were scared for their lives, and they ran away while their belongings were being ransacked on the streets,’ she said.

A shiver ran down my spine, but I also thought: ‘Why would they do that?’ I was too young then to gauge the grimness behind the seemingly unusual act of trying to escape one’s own identity: that I was too young to be able to appreciate, let alone, fully comprehend the reasons for their desperation is what she may have thought at the time as well. My mother must have avoided the details as reality is often a hideous slap in the face.

Some fifteen years later, when I found myself researching ‘Pilgrimonics’ in the UK with respect to the Harmandir Sahib (aka Golden Temple) in Amritsar, Panjab, I ended up asking my mother about the violent events of 1984 when this had happened. Her reasons for remaining silent on the subject she had borne witness to were different altogether this time round - or so, it seemed. With a word of caution: ‘Try to remain objective through it all - as a person, as an adult, as well as a woman.’ Then she bid me farewell on the phone. She still thinks I have a weak constitution or, maybe, that is how protective mothers are.

Despite the horror and the sorrow in which thousands lost their lives, I also learnt that the desecration of the Harmandir Sahib in June 1984 was one of the main reasons that a global community of Panjabis organised massive funding initiatives to rebuild the complex, especially the Akal Takht Sahib that was bombarded to rubble. It triggered recuperative measures nationally and transnationally, including from Britain.

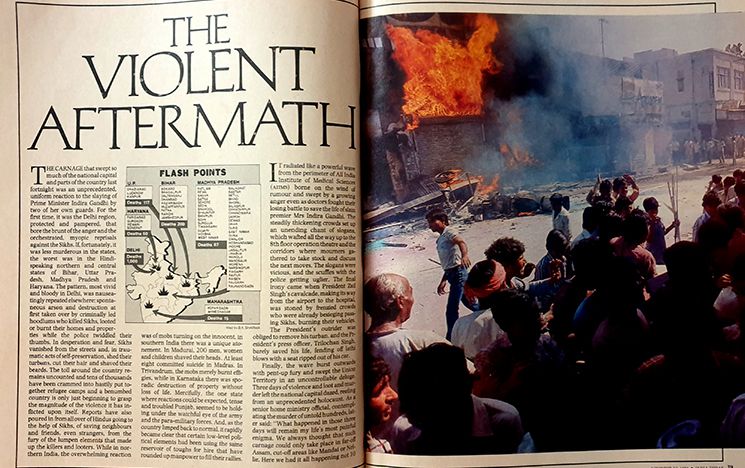

Figure 1. India Today's article on countrywide lynching of Sikhs after Gandhi's assassination

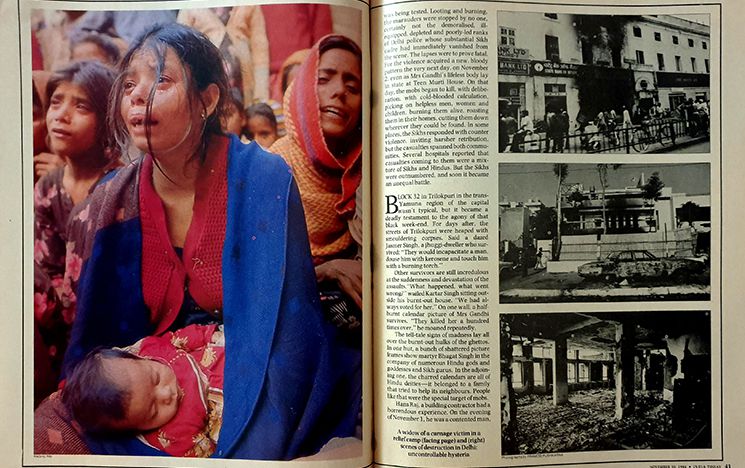

Figure 2. India Today's coverage of carnage struck Delhi in 1984

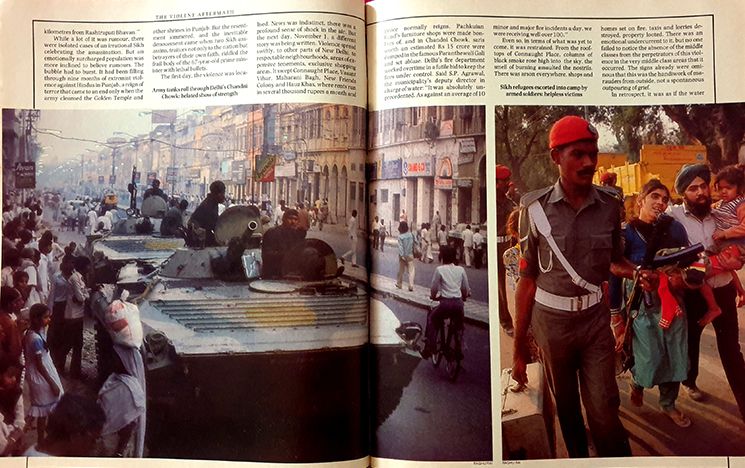

Figure 3. India Today on 'belated' police action on Delhi Sikh assaults

I now wish I had learned differently. How I wish I had raged and drowned in my tears because I now know what I did not know back then, while sipping the comforting chai, or rather, could not have known! I forgave myself for my ignorance and lack of curiosity. I had to, if I wanted to move ahead with the crucial task which was at hand - looking up ‘how’ and ‘why’ and ‘what for’ thousands of Sikhs lost not only their lives, but also their dignity and a place to call home in a matter of days after the assassination on October 31, 1984, while the prime minister was on her way to be interviewed by the British journalist Peter Ustinovos.The order of her day was to meet James Callaghan, former prime minister of Britain, followed by Margaret Thatcher, her contemporary, and lastly, the only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II, Princess Anne.

The statistics and the gory details of the events between the storming of the Harmandir Sahib in June and the aftermath of the assassination in November 1984 were anything but strange. We were all sitting at a table in July 2023 - a group of four theatre actors, a director, a scriptwriter, and myself. My assignment was to help with the research that would go into the writing of the script. This was to be based on eyewitness accounts of the desecration of the largest Sikh pilgrimage site, the Harmandir Sahib in the government-backed Operation Bluestar, and the pogroms and several unlawful imprisonments, torture and disappearances that followed under Operation Woodrose.

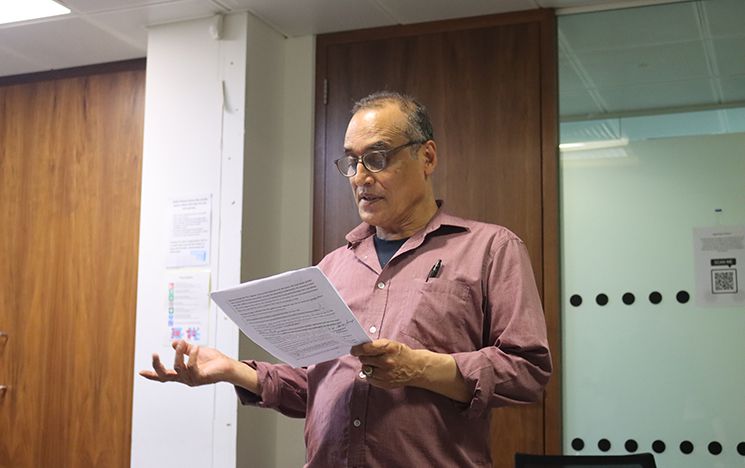

Figure 4. The four theatre actors engaging with the director in the workshop on the violence surrounding the storming of the Harmandir Sahib

The director, Christine Bacon, had distributed a reader. It contained several witness testimonies and it was a heavy read - so much so that I remember feeling an immense urge to have breaks every now and then. I wondered if she felt the same and thought it was necessary to plough through. She must be a champion of tough love, I thought.

Figure 5. An actor and the director listening intently to ongoing discussions in the workshop roundtable

Figure 6. Round table readings and discussions in the workshop

We kept our eyes peeled on the pages for intricate details of the incidents entailing turbaned men and boys being singled out by mobs to have rubber tyres put round their necks, doused in kerosene and then burnt alive, their houses aflame, and Sikh women abused and raped. As we lifted our eyes, from time to time, to look up at each other with faces full of unease and eyes almost cornering tears, we found ourselves speaking in heavy sighs and gasps. I wondered how courageous people can be, especially in times when conveniently overlooking realities are no longer options. They were not. At least not there, not then in the theatre, and not for the people we were in the act of remembering.

Figure 7. Actors reading on and discussing themes surrounding the 1984 violence

Figure 8. Actors reading on and discussing themes surrounding the 1984 violence

Figure 9. One of the actors reading an excerpt from the collection of 1984 survivor narratives out loud

The director wanted us, more importantly, the actors, to be completely immersed and invested in the testimonies. It reminded me of a scene from the Hindi film, Rang De Basanti (2006), when the young characters learn about their colonial history and those of six Indian revolutionaries who sacrificed their lives fighting for their nation’s freedom through a play that they were rehearsing.

Figure 10. Actors in pairs enacting two parallel scenes based on different themes from the 1984 carnage

Once the serenity of the morning had sharpened in intensity and after our eyes and hearts were weary of scouring the pages coloured red with carnage and mayhem for hours, the four actors were divided into pairs and asked to enact one scene each based on the readings. Their acts evoked pain and nostalgia and a shifting kaleidoscope of other intense emotions as they brought the real-life characters and sufferers to life - those whose destinies had been brought to a sudden halt or whose futures had slowly and painfully withered away after that unimaginable year.

Figure 11. Scenes from the workshop: Actors role-playing

Figure 12. Scenes from the workshop; Actors role-playing

Figure 13. Scenes from the workshop; Actors role-playing

Despite all the ambiguity that surrounds the total number of Sikh casualties given the array of state and national, international and community media figures, the one thing that had struck everyone present in the room was the scale and intensity of the violent assaults which the armed forces and the organised attackers had carried out on innocent pilgrims and devotees and on civilians in June and November, respectively. This was hitherto unknown to any of us except for Raminder Kaur, the scriptwriter.

The readings contained vivid eyewitness and survivor accounts, oral histories and lived testimonies of those who were around in the June 1984 and November 1984 attacks. June was significant because of the Operation Bluestar orchestrated by Indira Gandhi with some ill-advice from the Thatcher government, in the Harmandir Sahib because it was suspected to have become the hideout and operating base of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a hugely popular saint-soldier. Some had also started a fresh campaign for more autonomy (the ‘Khalistan movement’).

From June, Panjab was sealed off, communication and water supplies cut, and a curfew announced before the military attack on the Golden Temple and several other gurdwaras. International pilgrimage was difficult if not dangerous. One Surinder Singh, the hazuri ragi or supreme singer-musician, who continued performing his daily seva (selfless service) of rituals and kirtan (devotional music) despite the mayhem all around him related that 3rd June (a day before the final attack in 1984 started) was the anniversary of the fifth Sikh guru, Guru Arjan Dev’s martyrdom.

A volley of grenades and firepower rained on the Harmandir Sahib complex from the 4th of June. Singh as well as the granthi (head priest) and the other ragi had vowed that they would continue to render their services until the very last breath remained in their bodies. They performed continuously till the evening of the 5th until the army brought tanks into the heart of the temple. The ragi and the granthi did so without food and with the only hope that if they got shot in the act, they would be martyrs; if they got saved, it would be due to God’s mercy.

Several sevadar (volunteers) were shot and thousands lost their lives that evening, but Singh managed to escape, only to be arrested later on for being a turbaned Sikh in the Harmandir Sahib. As he spent time in Jodhpur jail with 364 others including women – all Sikh survivors of the attack and imprisoned by the state as terror suspects – his only wish was that their histories of resilience be told, and loudly so.

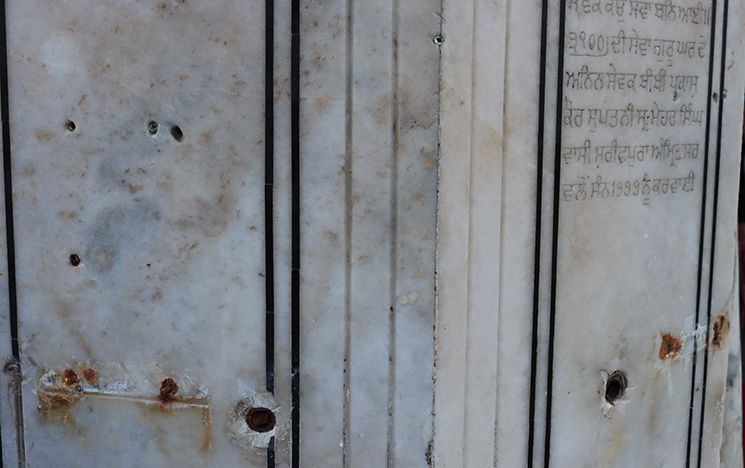

More significantly, in an act of destroying the memories and knowledge systems (epistemicide), the Sikh Reference Library around the Harmandir Sahib was infamously burned to the ground as the army took the valuable historical material away. While some of it was later returned by the government, the whereabouts of many of these items of Sikh heritage remain a mystery. All else that remain to this day are the bullets which had cut holes in the building wall as they had in the human bodies they passed through. These still stand as a grim yet gallant reminder of what had occurred in that deeply disconcerting month. ‘A picture is truly worth a thousand words,’ someone from the workshop submitted, ‘and there is no silencing that.’

Figure 14. Bullet holes in a marble wall of the Harmandir Sahib

Figure 15. Bullet holes from 1984 in a concrete pillar of the Harmandir Sahib

On the second day of the workshop, the silences got more deafening. By now, we were convinced that there had been an utter negation of human rights. The atrocities permeated by ruffians with the complicity of the police and powerful stakeholders in 1984 India, however, was anything but shocking to some of us who had been keeping ourselves abreast of the daily Indian news which were replete with similar such instances of caste and communal oppression. Media straightjacketing had unceremoniously impinged upon social justice then as it continues to do on many occasions even to this day. If we were to make a play out of this, the Herculean task of filling the gaps had to be accomplished.

Reliance on popular media narratives, therefore, was out of the question as they would only help collate a contorted bricolage of figures in the name of facts. Secondly, the sacrality, sanctity and security of the space where Bhindranwale went to seek asylum and where people such as the ragi showed exquisite courage and perseverance in the face of all odds, had to be recognised. Lastly, it was crucial that we found parallels to this incident – temporally as well as spatially – in India as well as in other countries, not because any other incident would hint at the unfathomable degree of loss and pain could come even an inch closer to what happened to the Sikhs in 1984, but because we could learn from similar such incidents to realise how important a fair retelling of the situation was – taking into account all sides of the picture and not omitting the voices of marginalised people.

The director helped by drawing comparisons with another play, Island Nation, that she had earlier directed on the Sri Lankan civil war and pogrom. She had learned from her experiences that presenting an unbiased narrative is far more important than simply adhering to a certain agenda. We all appeared to have a consensus that the marginalisation of Sikhs, albeit, a recurring episode in Indian history, had gained a contemporary spotlight only after 1984. Operation Woodrose and the orchestrated attacks in November only worsened the plight of Sikh communities. It was, by no means, an equal fight as the majority sided with the state whipped up by politicians and their henchmen in castigating a minority people to avenge the death of the country’s ‘Mother’ (Indira Gandhi), conveniently forgetting her role in political manipulation, authoritarian censorship and the forced sterilisation of the poor during the Emergency years from 1975 to 1977.

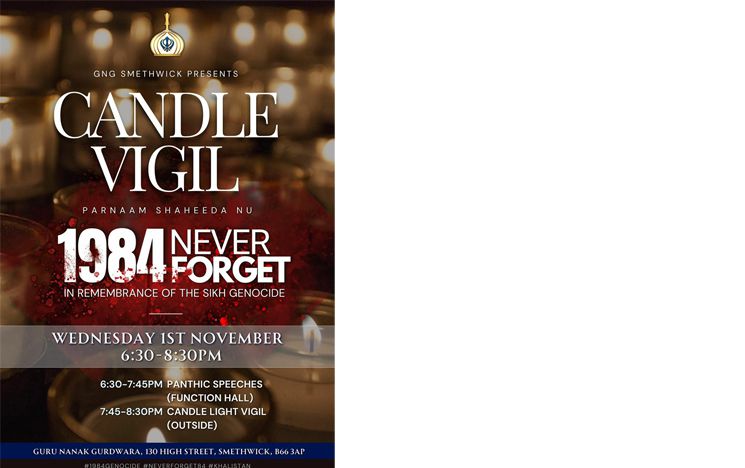

1984 is not just the name of a haunting novel but the year remains a blot on Indian history as a time when thousands of ordinary Sikhs were hounded and killed. The aftermath of this event marked a serious failure of justice if an Amnesty International article is to be believed. In this context, witness narratives become more relevant than ever. This play, to be written as part of a forty-year commemoration in 2024 seeks to bring to the fore the voices of the marginalised, and when it comes to widows and orphans, those of the marginalised among the marginalised. There has been a silence by the mainstream media around what actually happened in 1984, and continuing press censorship ensures that the pain around this silence remains unresolved – thereby, creating the need for greater reliance on individual narratives. Such narratives also become an important tool in highlighting what the state and wider public have consistently misconstrued or deliberated as riots were not actually riots but pogroms and even genocide. The ‘amnesia’ surrounding the very core of this truth needs to be unveiled. It is a gruesome event that is remembered annually across Sikh populations around the world, as happens regularly with a candle vigil by residents in the Birmingham area.

Figure 16. Poster of November 1, 2023 candle vigil, 'Parnaam Shaheed Nu (Saluting the martyrs); 1984: Never Forget; In remembrance of the Sikh Genocide' in Smethwick, Birmingham