Blessings

Raminder Kaur

‘Every time my mum was pregnant, she would go to the Harmandir Sahib to get blessings. Afterwards she would go with the baby. She did this three times.’

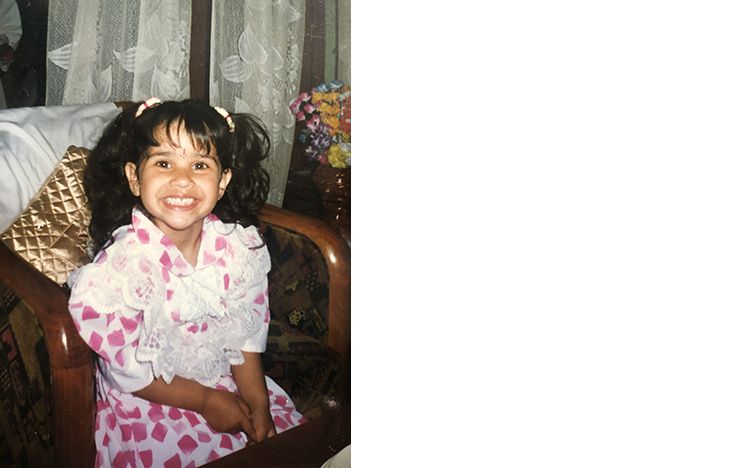

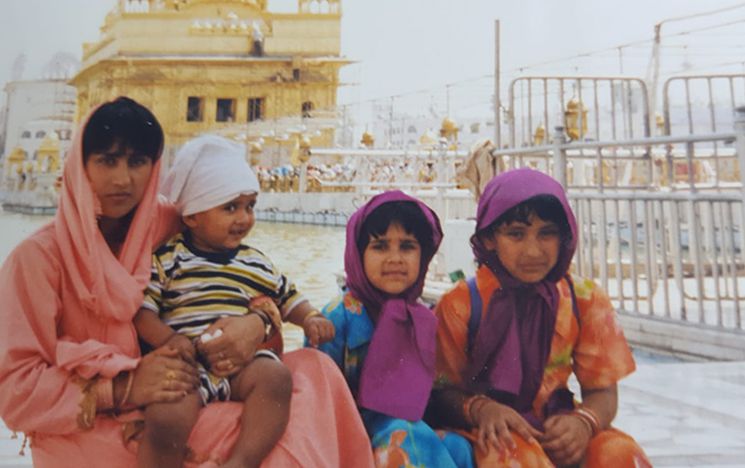

So recalled Ajayta Rai, an actor and corporate lawyer, who was born in Sandwell Hospital and grew up in Perry Barr in Birmingham with a younger brother and older sister (Figures 1 & 2)

Figure 1: Ajayta Rai at the age of 4, 1998

Figure 2: Ajayta Rai (child in centre) with her family at Harmandir Sahib, 1998

‘For my mother, the visit was a peaceful experience to start a new chapter in her life, and for it to be a beautiful chapter. The Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar was the best place to go and take those blessings. She didn’t know she was going to go again after that. So, it was a pleasant surprise to have more children. And my mother turned it into a tradition while she was pregnant, and made it a point to go to the Harmandir Sahib afterward with the baby. Altogether with us kids, she did this six times. My sister came with me when I was born when she was just three.’

Ajayta’s family respected religion but were not overly religious themselves. As a child, Ajayta used to regularly attend the Gurdwara Bebe Nanaki Ji or the Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha Gurdwara in Handsworth, Birmingham, every Sunday (Figure 3). With her family, they travelled to Amritsar in the 1990s from Heathrow airport with no limits on baggage: ‘My mother used to take a massive, massive suitcase. They used to take gifts such as British cloth to sew Panjabi suits, shirts, shoes, leather goods, all of that – quality items that were hard to get in India at the time.’ Their trip to Panjab combined religious donations, gifting and shopping trips to buy items that were hard to find in England at competitive prices.

Figure 3: Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha Gurdwara in Handsworth, Birmingham, 2023

She knew her vocation from the age of twelve as she recalled a conversation with her father, a lawyer:

‘ “Dad, I know what I’m going to do with my life - I want to be an actor.” I remember he laughed and said, “That’s not going to happen, you’re going to be a lawyer!” Then I guess my fate was sealed.’

And her interest in acting?

‘We always watched movies. I remember thinking – I want to do that, action scenes, travel to different countries, be creative, run around, be funny. We watched Bollywood movies a lot as well. Now that I’m an adult, I can follow both careers.’

I met Ajayta at theatre workshops in July 2023 with other actors, Rez Kabir, Anisa Butt and Joey Parsad and director, Christine Bacon that were funded by the School of Global Studies at the University of Sussex. We devised scenes for a script based on eye-witness accounts and testimonies of the storming of the Harmandir Sahib in 1984 (Sohaya Visions).

Ajayta’s last visit to the Harmandir Sahib was when she was fourteen years old in the 2000s as they were passing through Amritsar where their flight had landed. Her memories were blurred with previous experiences at the site – ones that she had embodied throughout the years:

‘I walked in towards the Clock Tower entrance, and dipped my feet in the water before you enter. It was absolutely freezing cold. I did not understand why I had to do it. And my parents said, “You have to do it.” I said, “OK, OK.” Then your feet are wet when you’re walking around. And a lady had a towel and she dried my feet off...'

I walked through the passageway and the gold was revealed to me. It was just breath-taking. I remember walking in and seeing massive goldfish in the sarovar. They were huge - like koi. I remember being scared of them at one point probably when I was younger. “Oh! They’re so big.” I remember that when I was a teenager, I was not scared anymore.’

Ajayta’s experiences of the Harmandir Sahib merged into one, activated through triggers like the cold water, the sparkle of the gold, and the curiosity with the fish (Figure 4), where any tedious aspects such as waiting in the long queue to enter the main shrine, or the Indian heat blurred into the background. She also remembered what she ate and donated:

Figure 4: Fish in the sarovar at Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar, 2023

‘I remember the prashad [devotional food] being white [patasa]. It was really sweet and that was really nice…I must have waited in the queue to go into the central shrine. I must have hated that and the heat beating down on you, but I don’t remember that part so well…I did my matha tek [bowing in obeisance while offering a donation] with Indian currency – rupees. The paper was so thin – easily rippable.’

We then laughed about how rupees could be renamed ripees!

For the workshop exercises, Ajayta dwelled upon her memories of violence visible in the architecture of the site (Figure 5-7):

Figures 5,6 & 7: Theatre workshops on the storming of the Harmandir Sahib (with actors, Ajayta Rai, Rez Kabir, Anisa Butt and Joey Parsad, 2022)

‘When I was fourteen, I knew what had happened in 1984 when the military stormed the Harmandir Sahib. My dad had told me before we went. I had that context when I walked in. I could not comprehend or understand the atrocity that happened here when it’s such a beautiful, calm, spiritual, serene and peaceful place. I remember being brought to tears. I was overwhelmed with how wonderful the experience was. I was quite young. It’s almost like the innocence that I had at that time, and not knowing the politics of it all, was tested at that time by the knowledge of the 1984 attack. You’re presented with this beautiful place, and you think of images of death all around you and you just can’t comprehend that. Even though I had not seen the atrocities, 9/11 in 2001 had happened before I went, and those images were going on in my head as well.’

Figure 8: Bullet holes on the side of the entrance to the Harmandir Sahib from the (para)military storming of the Harmandir Sahib in Operation Bluestar, 1984

Her experiences at the Harmandir Sahib were indispensable to her exploration of the topic of the workshops:

‘I don’t often think about going back to my experience of going to the Harmandir Sahib. The workshops were a good opportunity to rack my brain about my experiences. I remembered this feeling of absolute peace when I was there, and being brought to an emotional feeling, and then thinking about what happened in in 1984. I was dipping into and out of these experiences, and thinking back to how I was when I was fourteen. I carried those emotions through into the workshops. It gave me a bond and connection to be able to contribute to the discussions that we had and to some of the improv [improvisational] sessions that we did. It added an extra layer of information that I could draw upon.’

The night before the workshops, Ajayta had looked at blogs on YouTube to see what tourists see now at the Harmandir Sahib. She was curious to find out whether the events of 1984 were mentioned in any of their experiences:

‘It absolutely wasn’t! One particular blog was from a White couple from the UK who dressed head to toe in gold because they said, “We’re going to the Golden Temple.” They even wore gold shoes. I was drawing on that mindset. Tiny details such as the need to take your shoes off or covering your head before entering – they didn’t even know that. I drew upon such experiences of ignorance to a point.’

In the second improvisational session, Ajayta acted as a diasporic Sikh who came to visit the Harmandir Sahib. She explained her character:

‘I don’t know too much about what happened here, but I still got a familial connection to the place. So, I wanted to look harder at the bullet holes [from 1984] even though my other friend was distracting me. I wanted to learn about what happened because it impacts the way I look, the colour of my skin, who I am, my family, my blood. It was almost like it was an extra layer of responsibility. I felt a duty to know.’

While she drew upon her past and her experiences at the Harmandir Sahib for the theatre workshops, she also harboured aspiration for the future with a lingering question:

‘I hundred percent want to go back now, especially after this experience of the workshops. I’ll visit the Harmandir Sahib again. I want to go in the Akal Takht and take it all in [the building that was destroyed opposite the main shrine]. I’d like to explore the history of the area. Seeing the ragi [musicians-singers], hearing them. I’d like to see the fish again. They’ll be even bigger, I guess. I wonder what they feed them.’