The University of Sussex Special Collections have recently acquired the archive of Jeremy Hutchinson, Baron Hutchinson of Lullington QC (1915–2017). Best known to modernist scholars as one of the barristers for the defence of Penguin books during the trial of Lady Chatterley's Lover, Hutchinson's archive also stretches back to the life and writings of his father and mother, St John Hutchinson KC (who also defended D. H. Lawrence against charges of obscenity) and the Bloomsbury socialite, Mary Hutchinson.

Hutchinson was a celebrated barrister, considered by many of his generation to be the finest silk in practice at the criminal bar. He famously served on the team defending Penguin Books over their publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover; defended the director Michael Bogdanov of the National Theatre when Mary Whitehouse complained about The Romans in Britain; defended Christine Keeler when she was tried for perjury; and represented the drug-smuggler Howard Marks, the art forger Thomas Keating and the spies George Blake and John Vassall. Hutchinson is said to have been the model for John Mortimer’s Rumpole.

In the 1960 trial of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the chief prosecutor asked the jury (which consisted of 3 women and 9 men): ‘Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?’ He was met, infamously, with sniggers and laughter, his concern for the sensibilities of wives and servants already appearing at the dawn of the 1960s as a relic of times past. Amidst the letters contained within this extraordinary archive, the actress Peggy Ashcroft writes to her husband, Jeremy Hutchinson, a central member of the defence:

"I know how much this case means to you; and how much it means period. It has been marvellous to see you rising to it & grappling with it & I feel if only D.H.L. could have known what a satisfaction he would have had… The TRUTH is going to be said & it’s going to have such vast repercussions that whether it’s vindicated now or not that doesn’t really matter. The battle’s on & thank God some are there to fight it…’)."

Alongside annotated court papers, lists of witnesses, and correspondence on the trial from figures including John Betjeman, Stephen Spender and Leonard Woolf, the archive also includes a signed first edition of Lady Chatterley, gifted to Hutchinson by his mother, the Bloomsbury socialite Mary Hutchinson, and inscribed ‘In remembrance and honour of the great victory.’ As we approach the 60-year anniversary of the trial of Lady Chatterley this archive will surely add to our existing knowledge of this ‘great victory’ in British publishing and literary history.

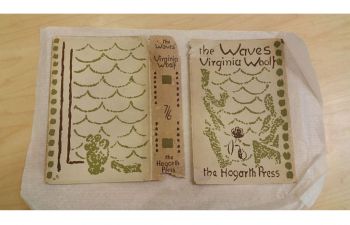

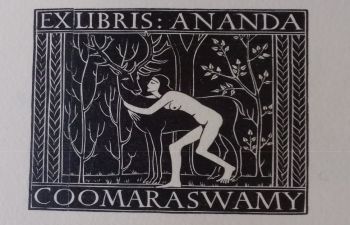

As well as opening up new perspectives on a trial that marked a victory over obscenity laws that had plagued modernist writers and artists throughout the early twentieth century, the catalogue for this extraordinary archive also reads like a ‘Who’s Who?’ of literary and artistic modernism, featuring appearances from Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell, T. S. Eliot, Henri Matisse, Paul Nash, W. B. Yeats, Nancy Cunard, and, of course, D. H. Lawrence. Amongst this extraordinary cast, the archive also brings new light to the life and work of Mary Hutchinson. Mary Hutchinson is perhaps best known as a patron of the arts (she was a supporter of Samuel Beckett and maintained a close relationship with T. S. Eliot and his wife Vivien), and for her relationships with Clive Bell, Aldous Huxley and Vita Sackville-West (one letter in this collection reads, tantalisingly, ‘Vita, I left a pearl earring on the table by your bed. I remember exactly where I put it – at the corner near you ….’), but the collection also contains a substantial archive of Mary Hutchinson’s own manuscripts and writings, opening up the literary output of a woman who has often appeared only in the more salacious footnotes of our histories of Bloomsbury modernism.