Artist in the Archives

Centre for Modernist Studies Artist in the Archives Scheme

The Centre for Modernist Studies has recently started an ‘Artist in the Archives’ scheme. The aim of this initiative is to invite artists, writers, poets, and other creatives to work with the Centre for Modernist Studies to create new artworks engaging with modernist experiments from the past in new and exciting ways. It is also an opportunity to work with archives, collections or histories relevant to modernism in the Sussex region. If you are interested in working with us in the future, please get in touch with the Centre directors Helen Tyson (H.Tyson@sussex.ac.uk) and Hope Wolf (H.Wolf@sussex.ac.uk).

Ane Thon Knutsen

2025 Artist in the Archives

Image courtesy of Ane Thon Knutsen

In 2025 our Artist in the Archives will be Dr Ane Thon Knutsen. Knutsen is a Norwegian graphic designer, researcher, artist and letterpress printer. She works as an associate professor and artistic researcher at The Oslo National Academy of The Arts and from her private letterpress studio.

Knutsen has presented, published and exhibited extensively in Norway, USA, UK, Portugal, China, Sweden and Poland. Her work is featured by the National Museum of Norway and in several American archives and private collections.

Justin Hopper

2024 Artist in the Archives

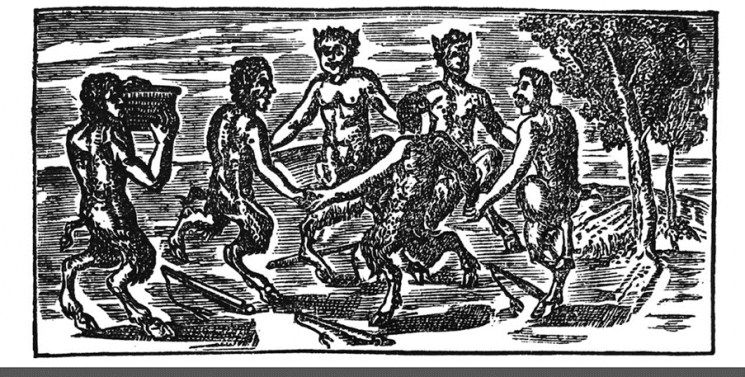

Image credit: Vine Press

The Artist in the Archives for 2023-4 was the writer, Justin Hopper, whose work explores the intersection of landscape, memory and myth.

Hopper was invited to collaborate with the Centre for Modernist Studies in part for his work on the South Downs area: his book The Old Weird Albion looks at the region through a series of poetic essays. We were interested too in his music-making. He has two albums on cult label Ghost Box Records: Chanctonbury Rings with Sharron Kraus, and The Path with Belbury Poly. Both combine landscape writing with music. However, we particularly wanted to develop a project with him around his fascinating book Obsolete Spells. This reveals the work and life of landscape poet, publisher and occultist Victor B. Neuburg.

In Steyning, West Sussex, in the 1920s, Neuburg set up a hand-cranked printing press and used it to create a new artistic network. By publishing books of poetry, prose and things in-between, Neuburg built a web that caught the educated and self-taught; the talented and having-a-go, as they documented Sussex culture and the strange rural-Bohemian life of the moment.

Hopper used this history as inspiration for a new printing project, inspired by Vine Press. On 20 May 2024, we ran an event called ‘Making Your Own Press: Printing a Pagan Bohemia in Sussex’. In the morning, we worked with the University of Sussex printing press. We printed a Neuburg poem alongside a Vine Press woodblock. In the afternoon we heard from a range of speakers who were, in different ways, inspired by Vine Press. We were joined by Caroline Neuburg, Victor Neuburg's granddaughter.

After the event Hopper created a Vine Press-inspired zine: A Sanctuary: New Writing & Art Work Inspired by Victor Neuburg and the Vine Press (2024). This included contributions on poetry, woodcuts, magic, Neuburg’s life, and 1920s countercultural practices. It also included poems and artworks that had been sent to him by participants in the ‘Making Your Own Press’ day. A creative community had been formed through engagement with Neuburg’s writing and Vine Press. The zine that Hopper created with designer Stefan Musgrove can be read online. A limited number of hard copies are potentially available on request.

The Vine Press project continues (see Hopper’s website for more details). For more on Hopper’s work see also his podcast Uncanny Landscapes. This provides a forum for in-depth interviews with contemporary landscape practitioners from the arts and sciences.

A.T. Kabe Wilson

2023 Artist in the Archives

Looking for Virginia

- Video transcript

I’m going to tell you a story. If you haven’t read To the Lighthouse, then please be warned this will contain spoilers. It will also include racist language and the constant interruption of me doing this…

because it’s the story of my journey through 100 different archives, and I’m going to count them all out. Any professional archivists watching will have to accept my apology for the occasionally loose interpretation of the word ‘archive’, and everyone will have to accept my apology if there are some questions I don’t provide the answers to. Most of the people I encountered on my journey were either alive, or lived in the twentieth century, so there were not only issues of ethics to consider, but also copyright. I don’t have permissions to show you every image I discovered, nor every name on each document I found, and there will be a lot of redactions to what you see. Some photos have been replaced with simple line sketches, and unless someone is a prominent figure or comfortable with me sharing their place in the story, I’ve changed nearly every name. There’s one notable exception to that rule.

It’s quite a complicated story, so my advice would be: don’t worry if you feel you’re losing your way or forgetting how the characters connect to each other. Ultimately there’s a movement toward clarity, or as at least as much clarity as the archive can offer. What I’ve come to realise over these years is that as much as we tell ourselves that archival research is about finding answers, it’s also about asking questions. That’s where every archival story begins. So it’s with a series of questions that I’m going to begin here.

If I were to ask you now to go to your old photo albums and find a picture of yourself on holiday when you were a child, not just any photo but one that meant a lot to you, maybe your favourite one. How much would you actually know about that photo? Would you know the date it was taken? Or even the year? Would you know exactly where it was? Would you know who took it? Would you know how you got to that location or who helped you get there? And If you had to confirm this information, how would you about that? Could you ask someone? Or would you have access to other kinds of records or clues to help you figure it all out? I’m asking these questions but the obvious response would be, what does it matter? Why would that information be important? And that’s a fair counter. But then our memories of childhood holidays can be very important. Virginia Woolf’s family holidays were so important to her that she wrote To the Lighthouse. And To the Lighthouse became so important to so many people that now Woolf scholars will study the photos taken on her family holidays hoping to answer the kind of questions I’ve just posed.

For me family holidays are significant because they mark happy and often highly impressionist memories of childhood, and they become knitted into the fabric of family bonding - they’re occasions you continue to refer back to over the years and that keeps the memories strong, even if the details themselves gradually fade. One of the best holidays we had when I was a child was a week-long youth Hostelling trip where we walked the Ridgeway. If you don’t know the Ridgeway, it’s a national trail in England that follows an ancient track about 90 miles across Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire and brings you up to finish in Buckinghamshire. And here’s one of my favourite photos from that walk.

This photo is from our fairly disorganised family photo box, but as perfect organisation of material isn’t a prerequisite for an archive, we’re going to call that our first one.

I was looking at this photo in 2019 when my stepfather asked me if I remembered the time he had sent one of the other photos from this holiday into the YHA - which is the Youth Hostels Association - and they had printed it in their magazine. Now this felt like completely new information to me, I couldn’t remember the story at all. But every person’s long-term memory is a unique archive, and as he searched his mind for more details, he remembered that one of my mum’s friends in London saw the photo of my brother and I and then posted her copy of the magazine to us. I asked if we still had it, but when he looked around the house he couldn’t find it anywhere. He felt convinced it would turn up if he kept looking, but I started to wonder where another copy might be. I was very excited to see it, because I love old photos, I loved all my memories of that holiday, and, mainly, I love a quest to find something that’s missing.

I googled to find out if the YHA had an archive somewhere that might have the back catalogue of their magazines. Sure enough, I discovered a catalogue list for the University of Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library suggesting that the issue I wanted to see would be held in their special collections. I didn’t mention this to my stepfather as it occurred to me that if he wasn’t able to find it in the house then me getting a scan or copy of it would be a nice present for his next birthday, and I made a note to myself that I would arrange to visit Birmingham at some point before then, knowing that I would first need to work out exactly when that holiday was, to know which magazine I’d need to request. Usefully, that wasn’t going to require me to dig through the whole family photo box, because years before this, as a gift for my mother’s 60th birthday, I had gone through the box and digitally scanned every photo in there. This meant I always had access to the images on my computer in case anything happened to damage the original photos. This folder is on my MacBook entitled: Photo Backups.

There was another birthday coming up before that though - my partner Eve would be turning 30, and I wanted to do something special for her present too. I’d had the idea of collecting together a photo of her from every birthday she’d had across her life and putting them together into an album. Initially this was quite easy, her mother went through all the nicely curated and captioned family photo albums that she’d made over the years and we just selected the best photo from each birthday party. I expected that the harder ones to source would be the ones I had to collect from more recent years, from adult birthdays where there wasn’t necessarily a party to mark it and I’d have to find them in my own phone archives or ask our friends. What I’d overlooked, was that our age meant that our teenage years, around the millennium, were marked by the advent of the mass use of digital cameras. This meant that the printed photos in her mother’s family albums stopped at this point,

and from then on we were looking for digital images - some taken as long as sixteen years earlier. Luckily her mother had been just as assiduous a family archivist in the digital realm as the analogue, and she had hundreds of equivalent albums from those years backed up on her MacBook. As digital photographs have the added benefit of the files, and sometimes even the images themselves, being timestamped I assumed that I now wouldn’t even need to rely on her having put the photos in folders named things like ‘14th birthday’, and I could just search for photos taken on the right date each year. However, this flagged an issue with digital media. This photo was in the folder for Eve’s 15th birthday, but the actual date of the photo file was the day after. That might not seem such an issue, but the time of the photo according to the file information was seven minutes past two in the morning, and her mother said this didn’t seem right. She remembered it as a school night and so all that happened was one friend came round for dinner. We checked online, and she was right, it was a Monday.

Because it’s very easy for digital cameras to have the date set wrong, I worried that we might be looking at photos that actually weren’t from her 15th birthday at all, and were maybe just from another night around the same time. We wanted to be sure, so we looked at some other photos they had taken that month for clues. We found this one, dated five days after her 15th birthday, that shows her brother and his friend drawing next to what looked like a poster or magazine for a caricaturist based in Brighton. I googled the name of the artist, along with the year 2004, and found the webpage for ‘Cartoon County the Sussex Cartoon and Comic Strip Artists Association’, that had an event listing for something called ‘The Big Draw 2004’ that this caricaturist had held at a restaurant next to the West Pier, five days after Eve’s 15th birthday. So we knew the date of the photo was right. But the poster for the cartoon event clearly noted that it was happening between midday and 4pm. The timestamp on the photo was 6pm.

Given that her brother is drawing on the first page of his sketchbook, it seemed likely that he was just starting rather than still drawing two hours after the event had ended - so we inferred from this that it wasn’t the date that had been set wrong on the camera - it would have merely been the time, and it was probably slow by about five hours. With that we could take five hours off the time of the birthday photo, and suddenly seven past two in the morning became more like 9pm in the evening, which seemed a fairly reasonable hour to be celebrating your 15th birthday with a friend and your family on a school night. Success. This was a pretty satisfying mystery to solve, we high-5ed, and moved onto the 16th. I should pause to note that I’m not going to recount the story of every digital photo archive we used to cover each birthday up to her 29th because they weren’t that varied or interesting. Her 16th was the key birthday, because looking for a photo of it took me down a path that would completely change my understanding of history and the archive.

We quickly saw that there was nothing in the iPhoto albums for her 16th, but her mother remembered there had been a big party for that birthday. She was sure there would be one somewhere so we tried looking through the box in the attic that held the photos she hadn’t sorted into albums. Again, nothing. Disappointed in herself for having no record of this significant moment in her daughter’s life she became quite invested in filling this archival gap and began suggesting different friends we might enlist to help. This was also ultimately fruitless, because no one had a photo from the night, but it did reveal how many of them had very clear memories of the event which had evidently been quite comically calamitous. As they bounced these memories back and forth with each other it really began to sound like an episode from a teen sitcom - involving everything you might expect to go wrong at a 16th birthday party - some boys turned up uninvited, a window was broken, a speaker set on fire, there was vomit, there was heartbreak, the car was mildly vandalised - really just all the ingredients of a suburban adolescent pantomime.

This also prompted her brother to remember that of all the calamitous things that had happened that night, the one with the most far-reaching consequences was the fact that someone had stolen the camera, and that was the reason there were no photos anywhere. Although this meant we were going to have to leave a gap in the thirty-birthday photo album, which was disappointing, after hearing all these funny stories of the party we decided instead to create a short mockumentary style video where each member of her family and the friends who came to the party could appear as talking heads giving their own account of what happened, really hamming up the farce, and we’d then play that video for Eve on her birthday. So they all recorded their clips and sent them to me to edit together, and this was the first point in the story where I created an archive rather than just consulting one.

When her friends were figuring out who had attended, as well as trying to find photos of her 17th and 18th birthdays, I spotted someone I knew in one of the profile pictures of someone they all knew. This is obviously quite a common occurrence with social media, that it reveals social connections you weren’t aware of, but the reason it stood out so much here was because the old friend I’d noticed was someone I knew from university who herself didn’t use Facebook - and so we’d lost touch years ago - she felt very much like a figure from the past.

This is her, my friend Jenny. And this is Eve’s party guest. I didn’t know how they knew each other, but the photo seemed to be a family holiday picture as it was a bunch of people of different ages standing together on a beach.

When I asked about the photo, I was told that they were cousins, and Jenny’s cousin encouraged me to get back in touch with her. I like reconnecting with old friends so I was keen to do so, but I didn’t immediately, because it started to occur to me that as much as I remembered Jenny fondly, I couldn’t actually remember that much about our friendship at university. Looking back, my general sense was that she was someone I’d had a really nice connection with for a couple of years, and who’d always seemed very interested in getting to know me better, but I found that it was pretty hard to remember that much, there were mainly just flashes of conversations I could recall having with her. It made me wonder how you even define a friendship if you’ve lost touch with someone and don’t really remember that much about when you were friends.

What I’m going to tell you now is not only one of the strangest moments of the story, but it’s also the one with the most frustratingly inaccessible archive. I don’t keep a dream diary. I have done, of sorts, occasionally in my life, but I didn’t around this time - which is near the end of 2019 and start of 2020, so I am unable to tell you for sure when this occurred. But at some point once I’d learned of this connection to Jenny, I had a dream about her. In the dream I was sitting in the back of a car, on the left-hand side, and she was sitting in the seat ahead of me, and a man sitting next to her was driving. I didn’t know where we were exactly but it seemed to be a pretty standard A road in the UK. That is all that I can recall of the dream. It could be that there was more to it than I’ve remembered, but I assumed she was just popping up in my unconscious because I had been thinking about her again.

Looking back, my feeling is that that dream is where it all began, because it introduced some sense of confusion about my memories. I don’t know that I thought of it on these terms straight away, but the best way to describe the feeling was that if my brain was a social archive, then Jenny had been misarchived somehow. I found myself thinking back on those flashes of conversation between us that I could remember, and trying to recall what form our friendship had actually taken, or how we’d even become friends. I’m someone who prides himself on his social memory, but conversations you had fourteen years ago don’t easily offer themselves up if you haven’t thought about them since, and because I’m quite a visual person, I could mostly just come up with scenes. There were three that stood out.

I remembered going to a house party that a friend named Jack had invited me to, and that when I arrived Jenny had immediately introduced herself to me. I remembered seeing her in the crowd at a play, realising she was staring over at me, and then one of her friends coming over to introduce himself to me afterwards. And I remembered seeing her walk past me on a bus, and I double-took because I found her face so striking. Putting them together these three memories created some confusion about how we had met, because it dawned on me that they didn’t really connect up in a logical way, and I couldn’t understand what the order would have been. I was fairly certain nothing had struck me as unusual about any of them at the time, but there was now something sitting there in my mind casting doubt on that reading that made me feel like I’d missed something. Because of this new doubt I occasionally found myself replaying these scenes in my head, focusing on Jack’s house party in particular, trying to build up a clearer image of that night and that first conversation with Jenny, hoping that if I had forgotten something, I might be able to draw it out of my mind all these years later.

As I said, this was in the early days of the pandemic so everyone’s plans were shifting around a lot at that stage as things got delayed or cancelled. I’d already been to Scotland to give a lecture and meet some students studying Virginia Woolf, but that had been before cases had really started to rise in the UK. My next scheduled event was that I was going to go to the Paul Mellon Centre in Bloomsbury to meet with Margaret Homans and her students so that I could talk to them about some of my earlier work on Woolf, which they’d been studying at Yale back in New Haven. I was excited about this talk, Margaret and I had been in correspondence for years but hadn’t met properly, and even though the first time I ever got to go to America was on the back of a Mellon Foundation grant, I’d actually never been to the Paul Mellon Centre, and had wanted to for a long time. I’d been especially looking forward to it because my plans for 2020 were to start painting again after a few years of mainly working in other media.

My story at this point is much like anyone else’s - my talk got cancelled, the students had to immediately fly back to Connecticut, so I didn’t get to visit the Paul Mellon Centre, and I didn’t get to meet Margaret. These were obviously minor frustrations in the context of what everyone was going through, but Margaret and I expressed our disappointment to one another and kept in touch across lockdown.

I’ve gone into detail about those turbulent lockdown months elsewhere, so the version of that story I’ll focus on here is where it connects to archives. In 2018 I’d been to see the exhibition of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant’s Famous Women Dinner Service, and had been thinking a lot about their work together since then. So when it came to painting in lockdown, I decided to start painting scenes of Brighton and Sussex - that followed a fairly loose conceptual pattern of being inspired by related paintings I had found by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.

I liked the idea that we were being drawn to painting the same spots a century apart, although for them this was plein air, whereas I was sitting at my desk, and working from old photographs I had at home from the last decade or so. As you can see, these paintings typically depicted landmarks along the seafront in Brighton and Hove, but the exception was the first one titled ‘Newhaven Lighthouse’. It’s called Newhaven Lighthouse because that’s what you can see in the mid-distance there, and what inspired me to produce this work was a 1938 oil painting by Vanessa Bell of Newhaven Lighthouse itself, which I knew was at Charleston, although I’d only seen it reproduced online. The reason I was particularly taken with this Vanessa Bell painting and wanted to channel it, was that Newhaven Lighthouse in Sussex is actually the closest lighthouse to both Monk’s House where Woolf lived, and Charleston where Bell lived.

It had occurred to me that Woolf had written much of To the Lighthouse when living at Monk’s House, so I had started to imagine her seeing Newhaven Lighthouse on the horizon and wondering if maybe this structure had become something her creative vision might have circled around, even though we know that it was Godrevy Lighthouse in St Ives in Cornwall that she really based the novel on - because that’s where her and Vanessa had gone on holidays when they were children. From what I’d read before no one had shown much critical interest in Newhaven Lighthouse, which I thought was a shame given its location and the way I imagined Woolf and Bell seeing it so often, and it seemed significant to me somehow that Bell had painted it, although her painting was from a decade after To the Lighthouse was published.

Now the conceptual pattern of the ten paintings I produced - of being drawn to the same spots that these Bloomsbury figures had once inhabited - did raise some issues and send me down some unexpected paths. At one point I was reading Woolf’s early letters from when she was holidaying in Hove in 1900 and found this quote:

“we go for walks along the Parade and moralise and look at the [BEEP].”

Putting aside the longer story of the discomforting experience I had reading these words, here I want to point out the capital letter - because this intrigued me. What I found when I looked into it was that it was a reference to the minstrel performers who would do live concerts on the seafront in the Victorian Era. Understanding that this marked Woolf’s early encounters with blackface got me thinking again about the Dreadnought Hoax, where she herself had blacked up as part of a prank in her 20s, pretending to be an Abyssinian Royal. As I dwelt on these thoughts I began looking into the history of black people in Sussex and discovered an incredible photo of Emperor Haile Selassie sitting on the deckchairs of the Palace Pier in 1938 while he was in forced exile from Ethiopia.

My penultimate painting of the series was the view of the sea from this same spot on the pier, that I then discovered matched a painting that Duncan Grant had produced in 1952. Gradually all these different archival threads were weaving together into a fascinating web that I was able to build on for a poetic piece I wrote about those lockdown months, titled ‘On Being Still’, which leant heavily on the sense of deferred travel that structures the plot of To the Lighthouse.

Margaret Homans and I had kept in touch over this period and she was following the development of my series and was generally interested in the fact that I was painting again. She told me she was still keen to work with me despite our Paul Mellon Centre event being cancelled, and knowing that I was thinking conceptually about To the Lighthouse, and that I had historically done so much close detail work on Woolf’s writing and word usage, she pitched an interesting idea to me. She asked if I thought I could go through the novel, draw out every reference to Lily Briscoe’s painting, and then recreate what the work would have looked like from those cues. I hadn’t read the novel for a few years and couldn’t immediately remember the extent of detail Woolf gave about Lily’s painting, so I went online to search through the text.

I told Margaret that while I liked the idea of the challenge, reading through the description of Lily’s painting reminded me that hers was a very abstract work, which was obviously unlike my own hyperrealist style, and I also had some trepidation in assuming the role of this iconic painter, when I was more comfortable being inspired by her through Vanessa Bell, whom she was to some extent based on. It also brought home to me just how much more I identified with James Ramsay at that point of lockdown, when the world seemed to be changing so quickly and dramatically, and yet we were restricted in travelling or visiting the people and places we most longed to see. That daily frustration of the young boy who wants to take a boat out to visit the lighthouse but can’t because of reasons beyond his control felt like something many of us could identify with. And it felt quite poetic that I’d become attached to this Vanessa Bell painting of a lighthouse at Charleston, but I knew it would be a long time before I would get the chance to see it. I should add that Charleston’s own future, like many cultural institutions at that moment in time, was uncertain. So I really didn’t know if I would ever get a chance to see the painting. And in fact despite having once lived in Sussex for a few years, I’d never been to Newhaven - I’d only seen the lighthouse from miles and miles away from a Brighton viewing tower.

But considering Margaret’s Lily Briscoe challenge drew me further back into the novel, and I started investigating this question of Newhaven Lighthouse and its influence on the sisters in more detail.

First, I sought to find out what they had ever written about Newhaven. Woolf wasn’t especially fond of Newhaven as a place. I found that in one of her diaries she even called it the ‘City of the Dead’, though in her defence a lot of her references were to the fact it was being bombed. By comparison, in 1936 Vanessa Bell sent a letter to her son where she talks about how much she and Duncan had been enjoying going to Newhaven harbour to paint. But both of these references were long after To the Lighthouse was written. When I looked into other occasions Bell had considered lighthouses I ended up on a blog created by the archivists at Charleston in 2014 when they were cataloguing a vast collection of Bell and Grant’s work donated by their daughter Angelica Garnett. One blog post included a photo of the tiled fireplace at Monk’s house that Vanessa had decorated for Virginia in 1930 with an image of Godrevy Lighthouse. This was an image I was familiar with, even though I’d never been to Godrevy lighthouse itself either. But this blog post also included a lighthouse sketch that I’d never seen before.

It was a simple line sketch, apparently by Bell, showing a lighthouse with a rounded top, then some waves behind it, and a sort of square block at the bottom. It was in a small sketchbook so I wondered if it might have been drawn from life - I could imagine her standing in front of a lighthouse quickly drawing what she could see. I obviously hoped it was a drawing of Newhaven Lighthouse. But when I compared the sketch with a photo of Newhaven, I could see that it clearly wasn’t - because they had totally different structural shapes about them at the top. I wondered if it was therefore Godrevy. But it looked even less like Godrevy - which is quite angular compared to Newhaven Lighthouse. While lighthouses generally have a basic design in common I was starting to see that they are all actually remarkably distinct from one another.

I looked up other lighthouses near Charleston. Belle Tout sits atop the Seven Sisters chalk cliffs, which are the further hills depicted in my painting. But Belle Tout wasn’t a match for the drawing either as it is much shorter and the lantern top is quite square. So I was a bit confused about this sketch - which lighthouse had Vanessa Bell drawn?

Then I realised - on the Newhaven local history website there was a photo archive showing a different lighthouse structure. There had apparently been an additional lighthouse at Newhaven harbour’s West Pier until it was damaged in the mid 1970s, and this West Pier lighthouse did have a rounded top, it also had a single window that seemed to match Bell’s drawing, as well as a lower structure matching the square shape she had drawn below. So it seemed very likely that this sketch was indeed of Newhaven Lighthouse, just not the same Newhaven Lighthouse I had painted, but a twin structure that had existed in Bell’s time and then been replaced years before I was born. The website said that the rounded top lantern had even been preserved and still existed in a theme park in the town.

This seemed to solve the mystery of the lighthouse sketch, but then something even more exciting occurred to me. The way the archivists had scanned the sketchbook page meant that some details from the sketch on the other side of the page were visible. It was a series of fairly abstract shapes, specifically vertical structures surrounded by cloud-like swirls. And they seemed very familiar to me because they looked so much like the original Hogarth Press dust jacket for To the Lighthouse - one of Vanessa Bell’s iconic covers. This felt like a thrilling discovery, because if I was right it meant that she had probably designed that cover immediately after visiting Newhaven and sketching West Pier Lighthouse for inspiration - so my theory that Newhaven was more significant than people had given it credit for might be substantiated by this sketchbook. I just had to see it to confirm. The problem was - Charleston was shut, everything was shut, so I wasn’t going to be able to go to their archive to check.

Although more culturally significant, this wasn’t the only theory I was ruminating on in this period. I had continued to think about Jenny as I tried to puzzle out the odd feeling attached to her in my memory. I’d asked a couple of my old friends if they remembered her, and my friend Nel had said ‘do you mean Jenny the mysterious girl?’. This was a bit of a lightbulb moment - I had forgotten that we had originally referred to her in that way. But looking back it was also a bit strange - because I couldn’t immediately recall what had been so mysterious about her, it seemed to connect with this growing curiosity I was now developing about her eagerness to introduce herself to me at that party and how we’d become friends. It felt like there was an unsolved mystery at the root of this friendship, and it was starting to draw me in.

What I’m going to say to you next comes with a serious advisory note. If you were born between 1980 and the millennium, it’s possible that you used to use a computer programme called Microsoft Network Messenger, or MSN messenger, to talk to your friends. Millions of these conversations are now lost to the ‘digital dark age’ - which is the time before we had the cloud or more reliable forms of archiving digital information. But if you are the type of person to have clicked ‘YES’ on the ‘archive message conversations’ option when installing MSN messenger, then your documents folder would have created a subfolder that holds XML files of those different message threads. If you are the type of person, let’s say, a visual artist, who needs to keep an ongoing hard drive backup of their old documents folder to keep a track of the paintings and other artworks they’ve created over their career, then you might as a result still have access to those XML files in that subfolder and therefore be able to go back and read the conversations you had with your friends in late adolescence and early adulthood. The advisory note is this. If you have access to that subfolder, DO NOT READ the conversations in that subfolder. The levels of cringe when you see what an obnoxious and embarrassing person you were at that point in your life can be pretty severe. But whether it was masochism or curiosity, I wanted to understand what this strange sense around my memories of Jenny was, so I dived into this archive to try and clarify things.

It was cognitively reassuring to see that the three early memories I had were fairly reliable, but seeing them as they’d been recorded at the time both helped fill in details I’d forgotten and allowed me to put them in historical order. I found a conversation thread with Nel, in March 2006, where I was recounting the night of the play - I told her I’d had a ‘weird but good night’, before describing someone I had seen around before and how ‘she walked past me on the way back from the bar for no reason’ and then how one of her friends had come over to talk to me, ‘nice guy, but he was strangely eager to find stuff out about me. I think he may have been put up to it’. I also saw reference to how this same friend had later written on my Facebook wall instructing me to upload a photo of myself. I then found a conversation I’d had with Nel the day after Jack’s house party, which was much later in 2006, where I was explaining how Jenny had approached me to introduce herself as soon as I’d arrived, as well as how well we appeared to get on, and how nice she seemed. I also found reference to a gig I’d attended a while before that, where ‘mysterious girl’ had arrived, and then smiled at me in a very friendly way as my friends and I left. I had forgotten this memory.

Put together, and in order, what became clear was that this ‘mysterious girl’ had been a presence in our social world for months before we finally met at their house party, and what had made her mysterious was her apparent interest in me - that is, until we became friends, the mystery lay in why this young woman was smiling at me or trying to find out more about me despite us having never met. Given that I have already noted that I found Jenny very striking when I first saw her, you might not see anything remarkable about this story so far. It’s just how 20-year olds often socially interact. But in order for you to understand why it suddenly stood out as unusual to me in retrospect, I need to pause here to quickly tell you another story, one that has always really fascinated me and that I have actually been telling people about for years.

In 2005 my friend Rasheed, who is one of my oldest friends, started a new relationship. He and his new girlfriend met in London, where Rasheed and I had been born and they dated for some time. A few months into the relationship Rasheed rang me up to tell me something incredible - they had discovered a photo of the three of us, that is Rasheed, his girlfriend and I, playing together as children. This was despite the fact that they hadn’t recognised each other at all before they started dating, and she and I hadn’t recognised each other when Rasheed had introduced us, and even looking at the photo prompted no memories for any of us that we had met her when we were children. What made it especially remarkable, was that the photo was not of us in London - the area where we’d all been born - it was at urban farm in Swindon named Lower Shaw Farm, where Rasheed and I had gone on countless holidays when we were younger, apparently at the same time as his eventual girlfriend.

Once we discovered this, everyone had different ways of analysing the story. As a portrait artist who’s so interested in faces, for me it seemed like a fascinating cognitive phenomenon - they had encountered each other as adults, and even though there had been some manner of recognition, it hadn’t established itself consciously as full recognition, and had instead prompted a kind of enchantment with each other’s faces. It also spoke to the magic of Lower Shaw Farm, as that was a place very special to all of us and the site of so many of our happiest childhood memories, even if not every detail of those memories had carried through to adult life.

So when I now considered this new question mark hovering over mine and Jenny’s friendship, I started to wonder - had the same thing happened? Or at least, had it happened for me? Was the mystery that I had seen her around and somehow not realised that I unconsciously recognised her from years before? Because looking at our early encounters through this lens made a lot more sense of how she had befriended me. That is, locking eyes with someone, walking past them hoping to get their attention, sending your friend over to ask them questions, smiling at them, soliciting photos of them, and then keenly introducing yourself when you get the chance - these are certainly things you might do if you recognised someone as an old friend but couldn’t immediately work out where you recognised them from. Which flagged the key question - if this theory was correct, then where did she recognise me from?

Initially I discounted the idea that it could have been Lower Shaw Farm again, because surely I would have remembered. But then I reasoned that I hadn’t remembered meeting Rasheed’s girlfriend there, even after we’d seen photo evidence of it happening. I thought back to meeting Jenny at her party, and what our first conversation had been. Although it was frustratingly difficult to recall, as I thought about it more, gradually two details from that night did come back to me. The first was that I had had a conversation about Virginia Woolf with Jack that evening - a conversation that we’d then continued onto Facebook the following day. The second was that Jenny had, understandably if she felt she recognised me, asked me where I’d grown up. I’d replied Nottingham - which is where my family moved to after I was born - and then I’d asked her in return. There was no link between her answer and mine, we’d grown up on different sides of England, but it now occurred to me that the place she’d said was a fair bit closer to Lower Shaw Farm than Nottingham was, and so the possibility that we had met there wasn’t something I could reject out of hand.

I started to consider the idea. If it was true then this was a really incredible realisation. It potentially meant that this friend I remembered fondly from early adulthood was actually a forgotten friend from childhood, and not just any point in childhood, but that she’d been part of a close-knit social community that had recurred across my life and made up many of my earliest and happiest memories. And yet, I couldn’t remember her there at all, and I was sure she’d never mentioned it to me, which was really confusing. As I didn’t have any evidence that supported the theory - I couldn’t really convince myself that it was anything more than that - a theory, and quite an outlandish one, largely just based on this sense I had of her being misarchived in my mind. So as keen as I was to know if it was true, clearly it wasn’t a good idea to ask her about it yet, in case I was wrong. I decided to see if I could confirm it.

The first place to check, fairly obviously, was the archive I had instantly available to me - my digitally backed up family photos. I checked if we had any Lower Shaw Farm photos in there. We did, but far fewer than I expected, they all seemed to be from one holiday and mainly just showed the older siblings of our extended group when they teenagers, there weren’t any of the younger set, which included Rasheed and I. But I was sure we had more photos than this, it suggested that my digital archive was incomplete, so I knew I was going to have to wait until I could get back to Nottingham to see what was missing.

So now, the list was the YHA archives in Birmingham, our family photo box in Nottingham and the Angelica Garnett Gift at Charleston. These mysteries that I hoped to solve but was prevented from doing so by the limitations of the time were starting to pile up. James Ramsay’s frustration at wanting to go To the Lighthouse had become my desire to go To the Archive, and it was becoming quite acute. Thankfully Margaret Homans was very interested in my Newhaven Lighthouse research and felt that Bell’s later focus on Newhaven was compelling enough even without the immediate confirmation of my theory about the mysterious lighthouse sketch, so she encouraged me to write it up as a short paper that might accompany the critical edition of To the Lighthouse that she was working on. She also sought my help in her own missing photo mystery - she was trying to work out which photo of Woolf and Bell’s mother was referred to in Leslie Stephen’s Mausoleum book, and this was something we were able to delve into using various digital sources.

Before I was finally able to go back to Nottingham to visit my family - I asked my sister to see if she could find the other Lower Shaw Farm photos. She looked in the box but said there weren’t many there, though she had found lots of the original negatives. This released a memory to me and explained where the missing photos were - I remembered that when I was a child I had compiled my own photo album of my favourite holiday photos, and I could picture what it looked like - it had a yellow pattern cover and plastic sleeves with the photos in and the first one was my favourite photo of all - one my stepfather took of us on a holiday in Dorset where I was burying my friend Ali in the sand at the beach. It made sense that the unscanned farm photos would be in there.

Although I couldn’t immediately find this album, I could see that the negatives my sister had collected together appeared to cover more than one trip to Lower Shaw Farm as well as other memorable childhood holidays, so I took them back home with me, thinking I could get the farm ones redeveloped. At this point it was starting to occur to me how limited my memories of these childhood holidays actually were. We had been to Lower Shaw Farm dozens of times over the years, but most of my early recollections of the place had now been replaced by later ones, and beyond the farm I could feel memories of the happiest days of childhood becoming less sharp as I got older. This was a sad realisation, so in fact having a reason to look through these old pictures felt like a nice way to reconnect with some of that history, especially at a time when the present was quite stressful and the future was so uncertain.

The fascinating thing about negative strips is that they maintain the order of photos as they were taken, which tells you a lot more about something like a holiday than just the collection of photos you might have grouped together randomly in a box, or even the curated selection you’ll put in a photo album. I found them to be a much more precise archive of our family holidays than anything I’d seen before, and that initially led to a certain amount of confusion for me. Unlike digital photos, they didn’t have dates on them, so even knowing what year they were from was difficult. It advanced the mystery of the YHA Ridgeway photo though, because I was able to tell from the negatives that the photo my stepfather had sent into the magazine had been of us standing at the end of the Ridgeway, at Ivinghoe Beacon. This was funny because it made me realise that I had unwittingly returned to that spot as an adult in 2013 on a walk with Eve’s family.

I also found this photo, which I assumed had to be a lighthouse in Dorset from the holiday where we went to the beach in Swanage and I buried Ali in the sand. But that beach photo wasn’t on the same film, and using my newfound skills as a lighthouse identifier I could also see that this lighthouse wasn’t any of those on the Dorset coast near Swanage. It was another mysterious lighthouse. Though in this case the mystery didn’t last long. From another photo in the same sleeve I was able to confirm that this was actually a lighthouse on Lundy Island, which is a tiny island off the coast of Devon where we went as a day trip on a separate family holiday.

I found my Swanage beach photo in another set of strips. But its placement didn’t really make sense - as it was among a set of photos of Lower Shaw Farm, which is in landlocked Swindon. That would have meant travelling to Swindon and then down to Swanage and then back to Swindon on the same holiday, which seemed like an odd journey.

This was the moment I requested access to the most important archive of my childhood. I showed my mum the photo of me burying Ali and asked why we had gone to Swanage in Dorset while we were staying at Lower Shaw Farm in Swindon. She looked at it and immediately explained that I had remembered the location wrong - this wasn’t a beach in Dorset at all, it wasn’t a beach at all, it was a lake, and the photo was of a Lower Shaw Farm day trip to the Cotswold Water Park in Cirencester near Swindon. I couldn’t accept this at first - it was my favourite photo and I remembered the moment so clearly, even the feeling of holding the spade in my hand as we patted the sand down over Ali’s feet - how could I have been so wrong about where it was? But I checked online, and of course she was right, it was the Cotswold Water Park Lake. So I took that whole strip of negatives back to the photo shop to get them digitally scanned at a higher resolution.

These were definitely the photos I’d put in my childhood album - they were very familiar to me, even though I hadn’t seen them in years. They generally showed our family friends at Lower Shaw Farm, or photos of the farm itself as I remembered it looking in the mid 90s and they brought back lovely memories of just how fun a space it had been for us all. There was only one photo that I didn’t recognise. It was the last on the roll, and was cut off halfway along, which suggested that it was probably never developed. This meant that not only was I seeing it for the first time, but it was the first time anyone had seen this image since the moment the photo had been taken.

This is my mum on the left, that’s me and Rasheed in the background holding table tennis bats, this is Ali here, and some of these people are other family friends. But this little girl in front of my mum. I didn’t know who that was. It wasn’t any of the lifelong friends from our connected group of families. But she did seem to be about my age. Was this Jenny? There was nothing to say that it was, but there was also nothing to say that it wasn’t. It seemed mind-blowing that it might be, and I really hoped it was her, but I had no reason to truly believe this theory, and it therefore still seemed a bad idea to ask her about it.

Then I looked at the beach photo, which I now had to call the lake photo and understand as part of that same holiday. I didn’t expect there to be any surprises here as I knew this photo so well. I’d never really looked at any of the other children in the background, mainly because you couldn’t see them clearly in the photo in my album. But this was a high-res digital scan - meaning it had significantly more detail than a developed 6x4 photo. This new level of detail did bring memories of the scene closer somehow, but it also struck me just how long ago that afternoon at the lake had been. It would be wrong to say that looking through these photos made me feel old, but it really did make me appreciate what a lifetime ago childhood was, and therefore how long I’d been alive. Part of me felt sad wondering if the memories of the day beyond this scene had simply been lost to the years, which was also frustrating given I now had such a curiosity to remember it better.

Then I noticed something. This man standing behind me. It wasn’t that he looked familiar, I’d never noticed him before and there wasn’t anything about him that seemed familiar to me at all. But the scene itself reminded me of something. It was that photo I had seen on Jenny’s cousin’s Facebook - the family beach holiday where I’d seen Jenny and found out they were related. I went back to it. This man had the exact same eyes, build, posture, height, shoulders, arms and hands as this man. It wasn’t a coincidence, it was the same man. I couldn’t believe it. It had to mean this was Jenny’s father. I really couldn’t believe it. It felt like a glitch in reality or as if someone had doctored the photo to play a trick on me. Until a few days earlier this photo marked a memory that had existed prominently in my mind as an afternoon at the Dorset seaside, and I’d accepted it as that for decades. And now I was not only having to rearchive it as a Lower Shaw Farm memory, but I was having to introduce Jenny’s father into the scene, a man who, as far as I knew, I had never met. But there he was, standing just a few metres behind me, which therefore suggested that Jenny had been there too, and that we actually had been friends as children.

Even though I’d sought these photos out on the basis of this theory, it was incredibly difficult to get my head around. In a way it was quite unnerving, but I was also excited and delighted at the realisation. This was the most mind-boggling archival discovery I’d ever made. I kept thinking back to the house party and the way Jenny had introduced herself. I wondered, did this mean that she’d actually known at the time but never told me? Or had she just recognised me and never worked out why? Had she maybe been too nervous to ask in case she was wrong? Or was it possible that she hadn’t been at Lower Shaw Farm itself, had we just met at the lake that one afternoon? And would she even remember any of this now? There were so many questions and I really wanted to know more. But I didn’t ask her immediately, we hadn’t seen each other in years, so I didn’t know if she’d find it strange to be asked about a holiday from nearly 30 years ago. But I was also paused by the fact that the people I showed the photos to were actually unconvinced by the likeness which was a problem because this photo was the only evidence I had that this pretty extraordinary theory was true.

What confused me was that this realisation still didn’t bring back any memories of the day at the lake or of that holiday itself. And when I visited family friends to check their photo albums and boxes not only did I fail to find any additional evidence to support my theory, but memories to back it up also continued to elude me. Seeing these old photos of us all did have a less direct effect on my memory though. I started having regular dreams where certain scenes recurred. They were never especially clear, but they often involved the activities I could remember being quite common for those holidays at the Farm - trips to swimming pools, playing football at the park, going to the cinema, and playing in different spaces within the farm itself. Jenny would occasionally appear in the dreams, but usually it was other old friends. Frequently these dreams would turn into frustrating quests to find a photo of myself that was always just out of reach - where I’d frantically search through boxes to find the one I was looking for. Researchers will often complain about the restrictive opening hours of archives, but when the archive is your own unconscious mind and you never know when it will open itself to you or what scant hints of information it will provide you with, you tend to start appreciating the work of underfunded physical archives much more. I just couldn’t remember anything significant at all. But these dreams reminded me of the original dream I’d had about being in a car, and I started to think that that had been a forgotten memory resurfacing. It implied that Jenny’s father may have driven us to the lake that day, which made it even stranger that I couldn’t remember them there with us.

When I eventually did contact Jenny to ask about the Farm, she didn’t reply. This might have led me to doubt my theory, but our old friends were quick to point out that she was well known for being very slow to get back to people and told me to be patient. I felt like James Ramsay being told that the weather might be fine tomorrow. I tried that for a while, and then I cracked. I asked Jenny’s cousin about the photos instead. This is when the self-doubt started to set in, because she didn’t think the man standing behind me at the lake was her uncle at all. She was very nice about it, but she sounded pretty certain, and I felt like James Ramsay being told the weather wouldn’t be fine tomorrow.

This put me in a slightly difficult position, because as adamant as I had been that I was correct, my friends and family refused to take my word for it over that of the man’s niece. Knowing how much I loved coincidences and solving mysteries, they felt I had just convinced myself something was true because it would have been such a magical story if it was. I was very uncomfortable with this, because I knew I was right, and I didn’t want them to think I was delusional, but I’m also arrogant enough that I really didn’t want them to think I was wrong about a question of perception. It was a very confusing situation, but even if my memory was no help, I became determined to somehow prove to everyone that I wasn’t deluded. Thankfully, the archive came to my aid. When I looked up Jenny’s dad I saw he had a LinkedIn profile for a company in the same region as the lake, that had been there for decades. There was also an old photo showing a much clearer likeness with my photo on the company website. And yet, despite having confirmed that it was him I still couldn’t remember meeting him. It seemed so strange that my brain could have released this vague memory of us travelling to the lake together, opening the possibility that we had potentially known each other for years in that period, but no useful part of it was coming back to my mind, even as my dreams still circled around images of what those holidays would have involved. I was so curious to know more, to reconnect the neurones to gain access to these dusty memories and solve this mystery of mine and Jenny’s apparently completely forgotten friendship.

The more I thought about that day at the lake, the more I faced the reality of ‘Time Passing’. In To the Lighthouse the middle section covers ten years between the childhood holiday and when they return. In the novel that seems like a long time, but I was reflecting on something that happened nearly thirty years ago. I resolved that I would one day like to return to the lake to see if being there brought back any of the memories, but I started to question the idea that this return would align with James Ramsay and his eventual journey to the Lighthouse. I was an artist, now moving toward middle age who had become absorbed with an image of someone else’s parent in a scene from a holiday years before, feeling that some detail was missing. I found myself starting to think more about Lily Briscoe, and wondering when and how I would finally have my vision.

Though I hadn’t yet told Margaret Homans about this shift in perspective toward the novel, after looking at my paintings and thinking about how much I’d been working on To the Lighthouse she felt it would be appropriate if my Newhaven Lighthouse painting adorned the cover of the edition she was editing. I told her it was a life goal to have one of my paintings on the cover of a Woolf novel, and it would especially mean a lot to me for it to be To the Lighthouse, as seeing a copy in a bookshop when I was 17 and being drawn to the cover, against prevailing wisdom, is what had begun my relationship with the work of Virginia Woolf, who was, at that point, basically unknown to me. To celebrate the fact my painting would accompany the novel, I decided to finally travel to Newhaven to see the lighthouse. I walked from the top of the downs and could see it on the horizon across the afternoon as I approached. It had been a difficult couple of years for everyone, but getting to do that walk actually underlined how much time had already passed since early 2020, and as much as I’d been dwelling on old memories and places from my past, it felt like such a relief to visit a new place that I’d been imagining reaching for so long.

As I moved toward the end of 2021 I began to reflect on my age more often. Not because I felt old or had any issue with getting older, but I was 35, and I knew that when I reached my next birthday I would then be the age my father was when he had died, which was in 1985, a few months before I was born.

Now aside from the fairly evident obsessive compulsions, I’m a pretty healthy person, so it wasn’t that I was necessarily dwelling on my own mortality, but parental precent is a powerful thing even in absence, so the prospect of being 36 in the year ahead did play on my mind, it felt like a poignant personal milestone, even more so since I’d spent so much of the last year thinking back over earlier periods of my life.

On New Year’s Day, just a few days after my birthday, Eve’s mother invited me to join her to visit a family friend who was staying with his elderly father at a house in rural Sussex. This was an intriguing prospect for two reasons. Firstly, I’d heard a lot about George, the elderly father, he was a former colonial administrator, now in his 90s, who was by all accounts a real character and had lived quite the life.

The second reason was that his granddaughter was a close friend of Jenny’s cousin - another one of the same crowd who had helped me with the 16th birthday video. At this point I was pretty anxious at the idea that that group of friends probably thought I was a fantasist because of my claims about the man in my lake photo. So I went along, thinking that if George’s granddaughter was there then I might be able to update her and slightly redeem my now potentially tarnished reputation among her friends.

She wasn’t there, but her grandfather turned out to be even more charming and interesting a figure than I had expected. Although he suffered from the short-term memory issues that often come with age, his long-term memory was astounding. After telling us stories all afternoon from across the eight decades of his later life, he mentioned his childhood in Nottingham. ‘I’m from Nottingham too’ I told him, ‘whereabouts?’ We quickly worked out that not only had we grown up in the same neighbourhoods, but amazingly our family houses were just a few doors apart. He excitedly started telling me about some research gaps in his memoir and instructing me to go find all the details he needed to fill them. I assured him I was an excellent archival researcher, without mentioning that that very fact had gotten me into a fairly unusual disagreement with one of his granddaughter’s friends, and I promised I’d source the information.

And so I did. By cross referencing the various memoir appendices he sent me, letters he had submitted to his school alumni newsletter, a Flickr account of local history, Nottingham newspaper archives, the Gazette and the government Register of Companies, I was able to answer the question that had frustrated him for so long as he had tried to remember a detail of family history from the 1930s. Delving into a research mystery that was both solvable and didn’t concern my own lost memories of childhood felt like a balm to my mind. Though ironically it did relate to my childhood, because the overlaps between his experiences of our neighbourhood and my own were remarkable given that we’d grown up more than half a century apart.

As I read his account of going to the end of the garden and staring down the steep bank toward the railway line below, I realised that this was the very same bank my childhood best friend had once tried to climb up, before falling down and ending up in hospital when we were 9. It reminded me of visiting him on the children’s ward and hearing his dopey explanation of the merits of morphine. In the 1960s that railway line had been discontinued, so as a 9-year-old it had never occurred to me why the ‘cliff’ that my friend had fallen down was even there. But now I understood why I’d heard rumours of a secret train tunnel near our house, and I went along and saw that the entrance to it was still slightly visible in the park where my mum used to walk our dog. The most startling overlap though was in George’s descriptions of Goose Fair - the yearly county fair held at a nearby park that had existed in the city for hundreds of years. The way he wrote about it chimed so exactly with my own experiences that it brought back memories of visiting the fair that I’d forgotten, which I found very moving and satisfying, given how much other memories had been recently eluding me.

I didn’t hear back from George, which was expected as I knew he probably didn’t remember meeting me, but I hoped that my research had helped with his memoir and I thought about him often, especially when I returned to Nottingham to visit my family. His reminiscences about Goose Fair stayed particularly strong in my mind, and when the Fair came around that autumn I suggested to my family that we all go down there the first time in years. That was just the evening plan though, my main reason for that trip to Nottingham was that I had promised I would finally get around to clearing out my old bedroom.

Anyone who has ever attempted this will know it’s no easy task. You are facing the most unruly archive of all, essentially an archive of archives, the museum of your life. In terms of artefacts bringing back forgotten memories, nothing could match this. I found rucksacks of old toys, letters from school, a plastic tub of my old CDs and cassettes, and sketchbooks of my own filled with drawings I didn’t remember doing. Here’s Dennis Bergkamp.

It’s a strange experience because in some sense time flattens out before you, and then you find yourself recognising the quite dramatic variety one life can hold. I was seeing documented evidence of childhood friendships that were so far removed from some of the bonds I’d made as an adult that it was jarring to imagine the different people I knew or had known now encountering each other. In one way this made me feel very lucky to have been able to experience such a broad range of social connections in life, but, reflecting on how much the current world seemed to be pulling itself apart through different forms of division, I also felt quite sad.

Then I came to the dusty cardboard box of my father’s stuff. This felt like an archive within an archive within an archive. I’d always known the general story of his life before he’d met my mother. He’d fled Ethiopia during the civil war in the 1970s, and ended up at a Sudanese refugee camp. From there he’d sought asylum to the UK and managed to get a postgraduate scholarship to study here, though he’d died before he’d submitted his PhD thesis. I knew this from what family and friends had told me, but seeing it in documented form was different, as now I could see the specific dates behind the story, which then slightly altered my understanding of his timeline. I was in a rush to switch the files into a waterproof box that could go in the attic, so I wasn’t looking through them in any great detail. One letter seemed to be from a scholarship organisation reminding my father that he needed to submit evidence of my parent’s wedding to the Home Office in order to legitimise his claim to remain in the country. I looked up at the date, grimacing at how long the so-called hostile environment had existed in this country and feeling angry that my parents had been subjected to this treatment by the state. But as I prepared to move the letter into its new box, I saw it.

At the top, just above my father’s name - it was George’s name. I couldn’t believe it, it was incredible, ghostly, shocking, and just profoundly confusing. But it was unmistakably him.

I looked out of my bedroom window and could see where George’s family had lived a hundred years ago. But this letter had been sent to my father when he lived in South London, meaning it had only travelled to Nottingham after he’d died and I’d been born. And then by a bizarre twist of fate, when we’d moved within Nottingham to this house in the mid-90s it had come with us, to take up residence, untouched for another 25 years, in an archive sitting about 100 yards from where George used to play in the garden as a child.

As I looked into it, by consulting the online archives related to the scholarship organisation and George’s son’s memories of this period, I understood that he had been part of the team securing government funding for these refugee scholarships. Because this scholarship had brought my father to London, where he’d met my mother, this meant that the old man who I’d met by accident one afternoon months before, partially because I’d been trying to solve my Lower Shaw Farm mystery, had actually played a pretty direct role in my existence. Across this year he’d gone from being the elderly father of a friend of Eve’s family of whom I was vaguely aware, to someone I could now picture walking past our family house in the 1930s, before growing up, travelling the world, and coming back to thread the social fabric that would ultimately make it possible for me to be born.

This discovery made me feel so inspired by the magic of human connectivity that old photos and documents could reveal, my archive fever had really taken over and I had such a thirst to know more, I even wondered if I’d be able to find a photo of my father and George together. A few months later we made a plan for me to visit George again, and so in advance of that, I went back to Nottingham, and back to the box, to see what else I could find in there.

This time I looked in more detail at the other formal documents and found that a lot of them were other applications for asylum or scholarships in different countries, some unsuccessful, some seemingly approved. It was a very strange window into lives that could have been. If my father had gone to China, or to Ireland, or to the USA, then my family wouldn’t be here now, none of this would be the same, our version of the world would just never have come into being. As I considered this chaotic reality of existence, I went through some of his written letters, which were separate. There weren’t many but one in particular caught my eye. It was short, on blue paper, and was from a woman in London informing him of the recent birth of her child. Though she invited him to come visit them, it was curiously ended with an apology that she was letting him down as a friend. What really caught my eye though, was that she signed it off… Virginia.

Although there was a date, and her address, there was no surname, just Virginia. At first I laughed to myself realising that the reason I knew this wasn’t from Virginia Woolf had less to do with the letter being sent 43 years after she died, and more to do with the fact that I knew her handwriting so well I could that tell this wasn’t her signature. And then I found this, my father’s reply.

After thanking her for writing he explains that:

“I have been meaning to write to you long ago but can’t seem to gather my thoughts…” “I was very shocked and disturbed for quite a long time after the last time I saw you; mainly concerning the end of our friendship and the marriage issue. Of course, I would not deny the fact that I was all the time and still I am confident of your honesty and sincerity and never suspected you would let me down after so long a time.” “I thought and assumed you understood very well why I have made a political decision to stay in Europe and particularly in Britain. And I think I told you my plans to fully participate in the class struggle when I am no longer under any threat with instant deportation.”

After raising the question of her interpretation of socialism in the UK he goes on,

“I believe I have fully understood the political and social pressures that led you to the abrupt decision of cancellation of the marriage we agreed upon. And I also thought that I fully understand why you do not want to infringe your independence in a society where your job and livelihood as a woman is constantly at risk and insecure by every passing day. But what you don’t seem to realise is that, it is the same capitalist system that makes you insecure that has made my life a nightmare. And I thought you knew very well the ’natural’ advantage you have over me and would be prepared to face the risks and social consequences of using that to defy the racist immigration laws of the British establishment; and I thought you were prepared to face all the consequences that that entails. Now that you have made up your mind I am not in any way trying to make you feel guilty but I do not see why I should interfere in your ‘peaceful’ life any more. And I am really sorry that our friendship had to end that way, and I have decided to be out of your independent life altogether for good.”

I really wasn’t prepared for this. I’d never read such an intense letter in my life. But looking for further details in the box revealed even more. I found a draft letter to the Home Office in my mother’s handwriting that recorded the story of how my parents met in a level of detail that was really none of the Home Office’s business. Accompanying this was a draft timetable she had compiled with the specific dates of their early relationship. From this I could see that my father’s letter to Virginia was dated just one month before he met my mother, and this confusing alternate timeline therefore ran incredibly close to our own. I had so many questions. Had he actually sent this letter, or just written it in anger when he realised he was facing deportation and potentially death? Was it a purely functional marriage agreement or had they been romantically involved? Was it possible her baby was related to me? And who was she? Who was Virginia?

This is the question that came to plague me over the following months. I was so desperate to know, but with no surname and very little to go on, at times it felt like the only thing I knew for sure was that she wasn’t Virginia Woolf. Though I wondered whether she might have been named after Virginia Woolf. She would have been the right age, and clearly this was a woman involved with feminist socialist political causes. I did check and confirm that it wasn’t Virginia Nicholson, Vanessa Bell’s granddaughter, and in fact I was able to rule out some other Virginias purely by knowing the new-born child’s first name and date of birth. Still, I found myself googling quite manically over the weeks that followed.

And the story grew even more mysterious when I confirmed that my mother had no knowledge of this relationship or the marriage agreement, nor had she ever seen the letters. It occurred to me that if everyone who had known about it had either died or forgotten, then these two letters sitting undisturbed in a box were the only evidence of this agreement in the entire world, and it was therefore possible I might never know more. Although I’d been finding it frustrating to not quite remember that afternoon at the lake, at least in that case I’d known where the missing information was stored. This Virginia mystery represented a whole other realm of archival frustration.

Not that I’d given up on my quest to better understand my lake photo. As much as I was still hopeful that Jenny would eventually get back to me, she hadn’t yet, so it remained an intriguing mystery, though one less ghostly than the Virginia letter. By this point I just craved more memories of the early days of Lower Shaw Farm, and felt that if I could find a photo or hear an anecdote to unlock those experiences I might at least stop having so many dreams about swimming, because even when I didn’t consciously try to remember the holiday, my brain would often continue trying to solve the puzzle as I slept. By now I had learnt to let the archive guide me, as it had already revealed so many of these amazing mystical connections from across and before my life, and so I put my faith in that to see where the quest might take me next.

One archive I still hadn’t had chance to check were the old photos that they had at Lower Shaw Farm itself. So I got in touch with Linda, who I hadn’t seen in years but had lived at the farm and organised our holidays there back in the 90s. I briefly explained about my search for childhood holiday photos and how that had aligned with my research on To the Lighthouse. Her reply brought maybe the most exciting revelation yet. She told me that they were currently housesitting in St Ives for a month, in a cottage facing across the bay toward Godrevy Lighthouse. She told me that she had been thinking of Lily Briscoe often, and she invited me to come and stay there with them so we could travel to the lighthouse together, and so I could tell them all about my discoveries.

That trip was a really magical experience. As my train came round the bay at dusk I caught my first glimpse of Godrevy blinking in the distance. And as I fell asleep that night, after having explained the first parts of my story to Linda and Martin over dinner, I could again see the light blinking in the darkness from where my head lay on the pillow. It was incredibly soothing. On my second evening in St Ives, they both opened up their memory banks to me and we shared our recollections of those days. It was exciting for me as it linked up previously disconnected images, and confirmed the theories I’d inferred from my recurring dreams. It was fascinating, because I was better able to understand the history of Lower Shaw Farm as a place that had created a supportive community for so many single mothers from South London, and it was also very moving as we remembered those members of that community that we’d lost in the years since.

Despite having returned to the farm every year or so across my adult life, it was this evening with them nearly 200 miles from Swindon that made me feel closest to those early memories. I’d also never felt closer to Woolf’s novel, and while it was a special experience to be able to walk round the corner and see Talland House, our trip to Godrevy, when the weather allowed it, was like a dream come true. Wanting to make my own archive of that day, across the afternoon I sketched what I could see of the lighthouse 30 times, as it came ever closer.

While I returned home feeling closer than ever to Virginia Woolf though, the other Virginia remained an enigma. I still had no idea who this mysterious woman was, or how she fitted into my past. I discovered the archival importance of a surname when the accessible register of births at the local library gave me too many results to be of any kind of use, and left me worrying that this story was destined to be an archive failure. Feeling thwarted, I decided instead to focus on my archival successes, because soon after this I finally got the chance to visit George again. As we shook hands for the second time he asked me, ‘why don’t I remember meeting you?’, which I inwardly thought was a good summation of how I felt towards his granddaughter’s friend’s cousin, and I thought about how strange it was that today would be such a memorable event for me, but for him all his most accessible memories lay so long in the past.

We bonded about the rivalry between our primary schools and he showed me photos from his life, as well as artefacts of historical significance to Nottingham, accompanying incredible and hilarious anecdotes about the city from long before my time. When I explained that he had secured the funding for the scholarship that brought my father from Ethiopia to the UK he told me the story of when he’d drank gin out of a pineapple with Emperor Haile Selassie. When I told him about my work on Woolf he told me about the time he had gone to visit the widowed Leonard Woolf at Monk’s House to share gardening tips. This man seemed to be one or two degrees of separation from every person or place I’d been interested in, and of all those I’d encountered, this ageing mind was probably the most impressive archival store of all.

Inspired by his memory, I felt embarrassed that I was only 37 but could have forgotten nearly an entire holiday, most of an adult friendship and the entirety of a childhood friendship with the same person, and it reignited my determination to finally solve the Lower Shaw Farm mystery. This time though, instead of thinking about the day at the lake, I tried to focus on Jack’s and Jenny’s house party. What if Jenny had told me her theory immediately upon meeting me and I’d just forgotten, or misinterpreted one of her many questions from over the years we’d been friends. I’d previously asked Jack about the party but he’d only remembered our conversation about Virginia Woolf. So I looked on Facebook to see if I could find any photos of us all from that night.