Why all Export Credit Agencies need to be on board to phase out fossil fuels

Ahead of the OECD export finance negotiations in mid-June, it is high-time for all export credit agencies (ECAs) to move from being a key contributor to the lock-in of fossil fuel infrastructure to becoming a key enabler for clean energy worldwide. This comment piece by Max Schmidt, Ziqun Jia and Igor Shishlov of Perspectives Climate Research suggests ways for ECAs to align officially supported export finance with the Paris Agreement.

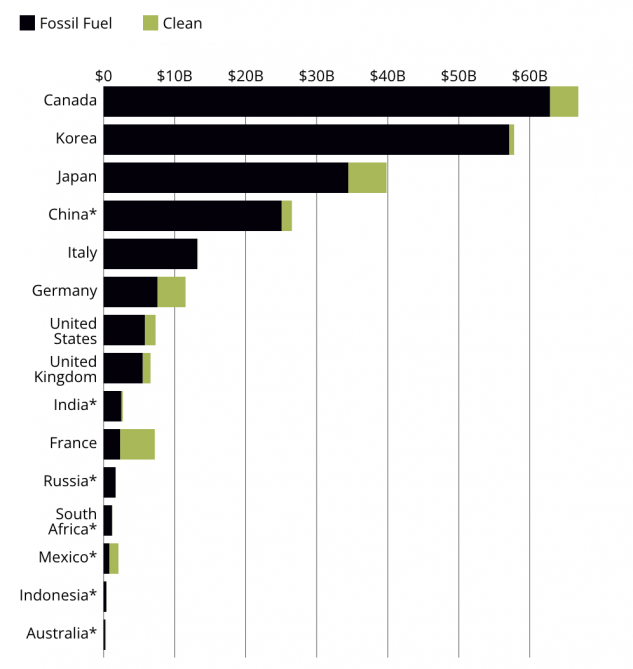

Every year, ECAs of the world’s biggest economies (G20) provide more than $32 billion in public finance to fossil fuel projects – six times greater than what they provide for clean energy. This makes them the largest class of G20 public finance institutions supporting fossil fuel investments, more than Multilateral Development Banks or bilateral Development Finance Institutions.

Figure 1: Public energy finance from G20 ECAs, annual average (2017-2022, cumulative)

*Limited or no direct reporting available (Oil Change International, 2024)

In principle, officially supported export finance is key to promoting the competitiveness of domestic companies in foreign markets. They are either public entities or private companies that act on behalf of a government. ECAs can provide, for example, guarantees to hedge against risks of an exporter or lender not being repaid due to political instability, expropriation, or unexpected currency fluctuations. They can also act as direct lenders and provide earmarked project finance or even equity instruments. Opting for a state-backed transaction can crowd in public and/or private co-finance and significantly de-risk deals for exporters - especially for large-scale, long-term or particularly risky infrastructure projects such as fossil fuels.

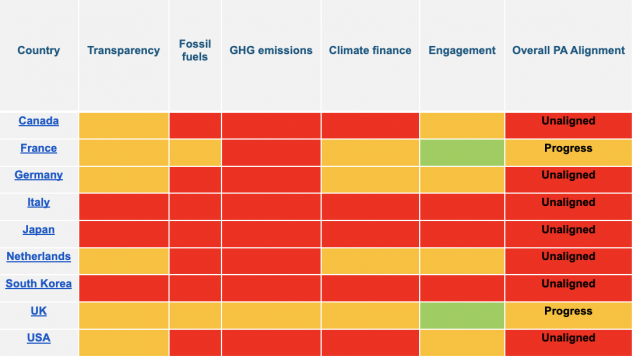

Over the past three years, Perspectives Climate Research assessed to what extent ECAs are and can become aligned with Article 2.1.c of the Paris Agreement (PA), in which Parties agreed to make “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions […].” So far, we have assessed nine different ECAs with our dedicated Paris alignment methodology which scores them across five weighted dimensions with 18 questions, underpinned by a total of 72 benchmark criteria (‘Unaligned’, ‘Some progress’, ‘Paris aligned’, ‘Transformational’). As of mid-2024, no ECA was found to be Paris-aligned, though some ECAs have demonstrated significant progress for reforming the export finance system in international and national fora, most notably France and the UK. Overall, an immediate stop to underwriting new contracts related to the entire fossil fuel value chain is needed to fulfill the pledge made at COP26 in Glasgow to cease international public support to fossil fuel investments, alongside greater transparency and more robust climate finance support.

Table 1: Overall assessment of nine selected ECAs in OECD countries

Note: For the case studies conducted first, the assessment result might now be different. For example, since the end of 2023, Germany no longer supports fossil fuel projects (with some loopholes for gas), and the Netherlands will stop doing so at the end of 2024. See further BothEnds (2024). Source: The authors.

It is not all bad news, however. Within the European Union, most ECAs – with the prominent exception of Italy – are already steering away from supporting fossil fuels, aided by the Export Finance for Future coalition founded by France in 2021. Since 2020, G20-ECAs have scaled up their support for renewable energy; and in 2023, negotiations of the OECD Arrangement on export credits granted ECAs new possibilities to support green and climate-positive projects, via extending repayment periods, making terms more flexible and reducing minimum guarantee payments.

At the same time, comprehensively reforming the OECD Arrangement is long overdue. Back in 2021, members only excluded support for unabated coal-fired power plants with various loopholes remaining. Since then, negotiations to add oil and gas restrictions have stalled. Colleagues with ties to OECD negotiators were informed of competing proposals between the EU and the US, with the latter proposing only GHG emission intensity thresholds (much like the coal support restrictions). ECAs within the OECD and beyond must do better as a matter of urgency.

The upcoming round of OECD negotiations in mid-June could be a turning point for a number of reasons. Firstly, ECAs can contribute to the global target of tripling renewable energy (RE) capacity by 2030, as best demonstrated by Denmark’s EIFO whose portfolio is dominated by RE-support. Secondly, ECAs can increase domestic energy security by supporting the import of critical minerals needed for the energy transition, as already done by Sweden’s EKN and the Export-Import Bank of the US. And thirdly ECAs can play an active role in decommissioning old fossil infrastructure. UKEF, for the first time, recently provided a GBP 7.5 million loan guarantee to a Brazilian firm to secure cutting-edge equipment from Scottish companies to remove hundreds of kilometers of subsea cables and pipes from defunct oil and gas rigs.

ECAs are well placed to demonstrate leadership. Around 40 countries have committed to end all international public finance for fossil fuel projects by the end of 2022, which could shift at least USD 28 billion per year into RE, on par with current G20 ECA support to fossil fuels. The five founding members of the new Net-Zero Export Credit Agencies Alliance (NZECA) have supported international trade with USD 120 billion in 2022. Alongside this, there are clear economic gains to be made. Most developed countries have at least one domestic sector with ambitions to export clean technologies internationally – from turbines (which can be used for RE instead of gas), climate adaptation technologies to grid and transmission infrastructure as well as clean transport. ECAs already have a plethora of instruments at hand to support domestic companies’ in these sectors . If a country does not have clean energy champions, its ECA can at least exclude climate-negative investments, even though ECAs like US-EXIM refer to their mandate of being ‘non-discriminatory’. Policy decisions over the scope and remit of ECAs are inevitably political, and if mandates have been found to be insufficient for changing priorities, like addressing the climate crisis, they must be amended or reformed – in the US as elsewhere.

Opposition against reforming the OECD Agreement to restrict export finance support to oil and gas is often based on arguments about competition with non-OECD countries such as the ‘BRICS’ members Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (and the new members of BRICS+). Though some of them are considered ‘OECD Key Partners’ with joint programmes of work, these countries and their ECAs are not obliged to follow the OECD rules. Like other non-OECD members, China has been operating under a different model and maintains great autonomy over the disclosure of transactions or (the absence of) restrictions. This explains why China was the largest financier of overseas coal-fired power plants for many years. While this model competes with many established OECD rules, OECD countries should not use ‘system competition’ as an excuse and instead scale up and fast-track their own support for clean energy export finance, as seen recently with battery gigafactories.

Finally, if individual or all OECD members were to withdraw from financing fossil fuel-related exports, it could create an opportunity for China and other non-OECD countries to fill the gap. However, the OECD’s progress should not stall because non-OECD members are not held to the same standards. The goal should be to reform the global export finance system, starting with the OECD. For example, China’s Sinosure has been a member of the export insurance industry’s Berne Union since 2009 but has not yet joined its Climate Working Group established in 2022. Close coordination with Sinosure and other non-OECD ECAs should help overcome the increasing fragmentation in the global export finance system, following the lead of NZECA with its affiliate members KazakhExport and the UAE’s Etihad Credit Insurance.

Instead of closer cooperation, though, most OECD countries are focusing on new protectionist measures, such as the EU’s anti-subsidy investigations of Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) or a 100% tariff on imports of Chinese EVs into the US, alongside marked-up tariffs on solar cells (50%), lithium-ion EV battery (25%), and critical minerals (25%). In response, China has shown signs of retaliating by launching an anti-dumping probe. New trade barriers such as these make the transition to a fossil-free future costlier and more difficult, undermine mutual trust, and push ECA cooperation further out of reach.

ECAs have a pivotal role to play in the global push to phase out fossil fuels. The forthcoming OECD export finance negotiations present a crucial opportunity for ECAs to transform themselves from being the world’s largest fossil fuel financiers to the champions of clean energy. Continuous progress within the EU and initiatives like the Export Finance for Future coalition and the Clean Energy Transition Partnership demonstrate the potential for change and the growing array of financial instruments at ECAs’ disposal. However, systematic reforms are needed to close loopholes and ensure that all ECAs support the energy transition globally. Instead of implementing protectionist measures that risk slowing down the global energy transition, the OECD ECAs and their governments should increase efforts to coordinate with non-OECD countries such as China to create a climate-aligned export finance system.

By Max Schmidt, Ziqun Jia and Igor Shishlov (Perspectives Climate Research)