The Largest Mosque in the World

Shadia Taha

‘We have seen photos of the Kabba hanging on the walls of our parents and grandparents’ homes. We have heard stories of what our families told us about these places. This is what is engraved in our memories.’

So reflected one of my interviewees from Birmingham when I visited Mecca as part of a group tour to perform Umrah in August 2023. Mecca is the city where Prophet Mohamed (Peace Be Upon Him ‘PBUH’) was born. It is also where he received the first revelations and where Islam was born. Hajj, pilgrimage to Mecca’s holy sites, is one of the five pillars of Islam and is obligatory to all physically and financially able Muslims to perform at least once in their lifetime. As such, Islam is the only religion where pilgrimage is mandatory, and Mecca has continued to be the principal location, the focal point, and beating heart of Islam for all Muslims.

Throughout its history, Mecca was a commercial center for caravans from Iraq, Yemen, Syria and other trade routes even before the birth of Islam. Mecca, Madina and Jeddah were located in the Kingdom of Hejaz until they were taken over by Saudi Arabia and added to the Kingdom in 1932.

Al Haram Al Sharif Mecca encompasses the Kabba, one of the holiest sites in Islam towards which all Muslims pray

Figure 1: Kabba, the most sacred site in Islam

Built by Prophet Ibrahim and his son Ismail. The Kabba cubical has four corners. Those are: 1-Al Rukun Al Aswad (The Black Stone) located in the southeast corner and sacred to all Muslims (Fig.2); 2-Rukin Iraqi (The Iraqi corner); 3 Rukin Al Sahmiy (The Levant corner); 4-Rukun Al Yaminy (Yemen corner). Beyond the Black Stone lies, Maqam Ibrahim.

Figure 2: Maqam -Ibrahim, one of the most cherished places in Islam.

Figure 3: Al Safa and Marwa after renovations.

Al Safa and Al Marwa are two small hills. Al Sai between Safa and Marwa means running between the two hill seven times (total of 3.6 km -2.3 miles). Al Sai ritual replicates Hajir running between Al Safa and Al Marwa searching for water and running back to check on infant Ismail.

Figure 4: The Kabba eclipsed by the skyscrapers.

It is a crucial part of Hajj and Umrah rituals. There have been a number of changes at Al Haram Al Sharif throughout time. However, developments from the 1980s to the present significantly altered the historic religious landscape. With the new alterations, the Kabba is no longer the highest building in Mecca and the building that every pilgrim sees when entering the city.

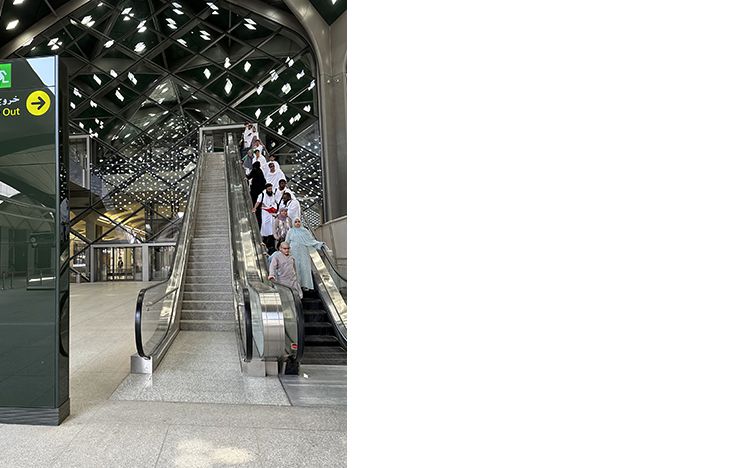

Figure 5: Escalators to go down to get to Kabba.

Indeed, today, you cannot see the Black Stone from the skyline at all rather pilgrims have to take escalators to go down to see it.

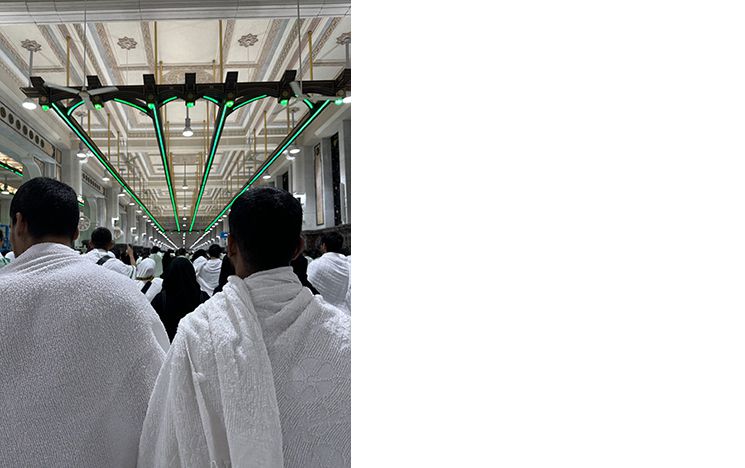

Figure 6: Al Sai between Al Safa and Marwa in the Modernised Mosque

Extension of the Grand Mosque continues to this day, and building work and cranes are visible around Al Haram Al Sharif.

Figure 7: Cranes surrounds Al Haram Sherif: Expansion of the Mosque continues

So too for the Zamzam well, unseen since construction ended and from where Zamzam water is distributed directly in dispensers and water bottles. Safa and Marwa are also reached by escalators, the floor is covered with marble and stones covered with varnish to stop pilgrims taking stones home as memorabilia.

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries witnessed the biggest changes to Al Masjid Al Sarif Mecca. Owing to commercial air travel reducing journey times and costs, more and more Muslims travel to the Holly Land. Additionally, Saudi Arabia’s oil prosperity enabled the rulers to finance massive construction schemes. Al Saud’s extension of the Grand Mosque was started by King Fahad and King Abdullah in 1989 and 2008. King Salman Bin Abdelaziz project enlarged the Grand Mosques by two thirds.

The recent developments include multilevel spaces for prayers. There are four levels inside the Grand Mosque: basement, ground, first and roof level. Women and children are only allowed to use the roof level during the Hajj season. Beyond the Mosque, the compound includes six new floors for prayers, 21,000 toilets, 860 escalators and 24 lifts for pilgrims.

The entrance to the compound is by stairs and escalators. Air conditioning, a communications network, lifts, lights, sound systems, video surveillance, fire control measures, and a huge full-time staff and security are available all day and night. With the latest expansion, Al Haram Al Sharif has become the largest Mosque in the world. The number of Hajjis in 2023 who travelled to Mecca and prayed at the Mosque was over 2.5 million.

Since the 1930s Saudi Arabia relied mainly on oil income amounting to 30-40% of the Saudi Gross Domestic Product. However, dependence on oil as the main source of revenue is unpredictable, especially because of the fluctuation in oil prices and on decreasing dependency on oil leading to a decline in the Saudi Arabian economy. Therefore, it has been the kingdom’s latter-day aim to diversify their economy.

Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 declared by the Crown Prince and Prime Minister Mohamed Bin Salman on 25th April 2016 aims to make Hajj and tourism as the number one source of income and to diversify its range of products The kingdom started to build more tourists resorts, and grant tourist visas. Nowadays, women are allowed to travel on their own without a Mahram, a male escort such as her father, husband, son, or brother – that is, a person a woman is not allowed to marry. And entrance to the country is no longer just for Hajj, Umrah or work reasons. It also for the first time includes tourism.

Owing to Mecca’s and Madina’s appeal and their significance to the Muslim world and millions of worshipers, the two holy cities are currently the main source of revenue in terms of employment, hotels, visas, fees, transport, food, accommodation, and related services for Saudi Arabia’s non-oil economy, totaling some $12bn in revenue. Saudi Arabia is now spending billions of pounds on tourism and infrastructure, maximizing strategies to promote tourism and heritage and to represent the country status as a modern Islamic and cultural terminus for religiously-orientated visitors.

Al Haram Al Sharif is an extensive compound; but despite the developments, there is no sign posting. Entrance to prayer areas and doors have numbers. Nevertheless, you could not get there without asking the guards and security staff, who are there to help. Amongst the millions of visitors, what makes it more confusing is that there is a separate gate and entrance for those who are performing Umrah and those who are there to pray. Everyone has to stop and ask for directions. This creates unnecessary delays.

Witnessing first-hand the number of people who embarked on Umrah this year was incredible. The numbers are extraordinary, with every inch of the mosque occupied. Sometimes I could not even find a place to stand. Even for Umrah as it is for Hajj, to find space for prayers, pilgrims need to leave early to secure a space inside the Mosque. When inside, I couldn’t even raise my hands to take a photograph. The best option is to stand on the surrounding roof to capture the size of the crowd.

After our prayers, it took a long time to get out of the Mosque. I was walking with an Egyptian woman I met who told me that on the 30th of July when she visited before the month of Maharam, even at 3 am, the crowd performing Umrah was so enormous, that security was worried that there may be casualties and even fatalities. They had to stop pilgrims going in altogether.

Pilgrims who performed Hajj or Umrah in the 1980s or 1990s remembered the holy sites before the new transformation. They were very disappointed as the image of what they remember from their first visit has changed.

Our group travelled from Madina to Mecca by a speed train The Haramain’ which means connecting the two Haram Al Sharif Mosques. The journey involved a two-and-a-half-hour train and forty-five minute forty-five-minute bus journey to the train station, and vice versa. Being on my own and on my first Umrah, I was a little nervous. The journey gave me the opportunity to talk to people in my group and make friendships as we were all on the pilgrimage together. My seat was situated next to a woman from the West Midlands, who had been on Hajj and Umrah several times before. She commented on how the Safa and Marwa have been covered with marble rather than the original natural path. The marble is slippery, and it did not provide an authentic experience in her eyes as her feet where not in direct contact with the original paths. Another young woman told me, she travels to Umrah every year, and with every visit, she sees more and more changes.

As we completed our pilgrimage, there was a notable disappointment on the faces of members of the group I travelled with to perform Umrah and Hajjis that had the pleasure of coming back to the Holy Land. They talked about how it seemed that they were in the Westen World with countless malls and shopping centers at the feet of their hotels whose architecture had no touch of Islamic style. There seems to be a disconnection with the pilgrimage and the birthplace of Islam with these modern modifications. Another woman remarked that it is all about money these days – money spent on fast food (like McDonalds), expensive luxury brands and other merchandise.

I too experienced similar feelings on this sacred journey. It was hard to picture and visualise the stories I have been told by older members of my family when I was growing up in Sudan. Yes, we may have been looking at the same Kaaba from the pictures in our homes, but it was surrounded by something that seemed very incongruous in the evolving landscape around this central site of Islam. I felt younger generations and first-time visitors, myself included, were robbed of experiencing the historic landscape and feeling immersed in the past to stories in the Quran. Connecting historical events to contemporary places was challenging. While I experienced exhilaration for visiting this supremely sacrosanct place, it also left a feeling of unease as to how investments and developments around it might emaciate the heart of sacrality.