Shining a light on the impact of pesticides on bees

Professor Dave Goulson’s research into the impact of pesticides on bumblebees has been widely cited in the media, and has led governments to take action to better protect insects.

Given that Dave Goulson, Professor of Biology at the University of Sussex, and his research group only began looking at the effects of pesticides in bumblebees in 2010, it’s amazing to see what they have accomplished in only 9 years.

Goulson had set up a charity called the Bumblebee Conservation Trust in 2006, followed later by the citizen science Buzz Club after he came to the conclusion that publishing research in academic journals “was a bit pointless”. “The only people reading my research were a handful of academics who weren’t able to do anything practical to help bees any more than I was.” The Bumblebee Conservation Trust now has more than 40 staff and 10,000 members.

Dave Goulson meeting with citizen scientists part of the Buzz Club.

In 2010, members of the Trust began to suggest that there may be a link between bumblebee declines and pesticide use. Bumblebees feed on and pollinate wildflowers and help produce much of the food we eat, including crops such as tomatoes, runner beans, raspberries, apples and strawberries. “Our members were adamant that we needed to address the pesticide issue because they thought they were poisoning bees,” Goulson said. “I have to admit I was sceptical to start with. I wasn’t convinced that we’d find very much.” Despite his reservations, he decided to follow the line of enquiry suggested by the Trust’s members.

In 2012 they exposed 75 bumblebee nests to neonicotinoids, neurotoxic insecticides used to control pests, and found that the pesticides had a devastating impact on the queen bees. The research revealed that colonies of bumble bees, Bombus terrestris, exposed to levels of neonicotinoids similar to those found in fields of insecticide-treated crops suffered from an 85% reduction in the production of new queen bees compared to control colonies. Queen bees are necessary for the establishment of new bee colonies the following year – so an 85% reduction should have set alarm bells ringing.

A buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris), one of seven species of bumblebee which are widespread across most of Britain. Credit: Creative Commons, Steven Falk.

It got a lot of media coverage and launched Goulson’s research into the impact of pesticides on bees. “Before I knew it, I was embroiled in this very political debate about pesticides.” The research provided important evidence to the European Food Standards agency, which was commissioned by the European Parliament to review the impacts of the chemicals. The review directly led to a 2013 European Union moratorium preventing the use of the three pesticides – clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoam – on flowering crops such as oil seed rape and sunflowersthat appeal to bees and other pollinating insects. The UK was among the nations opposing the ban at the time. Last year the EU expanded the pesticide restriction to all field crops, although they can still be used in sealed greenhouses.

While these are significant and important steps in the right direction, neonicotinoids are still the most widely used insecticides in the world. Goulson is working to change that. He has given talks related to bees and pesticides in the Paris Senate, to the government of Ontario, a province in Canada, and the US Congress. While the current US administration has overturned a ban on the pesticides brought in under Barack Obama, the province of Ontario passed new regulations in 2015 to reduce the use of the insecticides by 80%. Goulson wrote an open letter in 2018 calling for national and international agreements to “greatly restrict” the use of neonics, which has been signed by more than 232 scientists.

It’s my duty to hold governments to account and to keep badgering them until they do something. Scientists should be prepared to stand up when they think government has made the wrong decision, and say so. If we don’t do it, who will?”Dave Goulson

Professor of Biology, University of Sussex

Dramatic plunges in insect numbers highlighted in recent research Goulson co-authored highlights the urgency of the problem: the number of flying insects has fallen by three-quarters in 27 years. Concerningly, the flying insects were captured in nature reserves across Germany; declines are likely to be higher in urban or heavily farmed areas. “It’s terrifying,” said Goulson commenting on the research. “Insects are at the heart of everything. They pollinate most of the crops we grow – they pollinate more than 80% of wildflowers. They help recycle nutrients. They are predators of pests. If we lose insects, life on earth will collapse.”

The research was widely covered in the media and was cited by the UK’s former environment secretary, Michael Gove, as key to his rationale for supporting an EU ban on the use of neonicotinoids, reversing the UK governments’ previous position on the insecticides. “When the science shows that our environment is in increasing danger we have to act”, he wrote in The Guardian, directly referencing the German study. Gove has said that the UK government will keep those restrictions in place after leaving the EU.

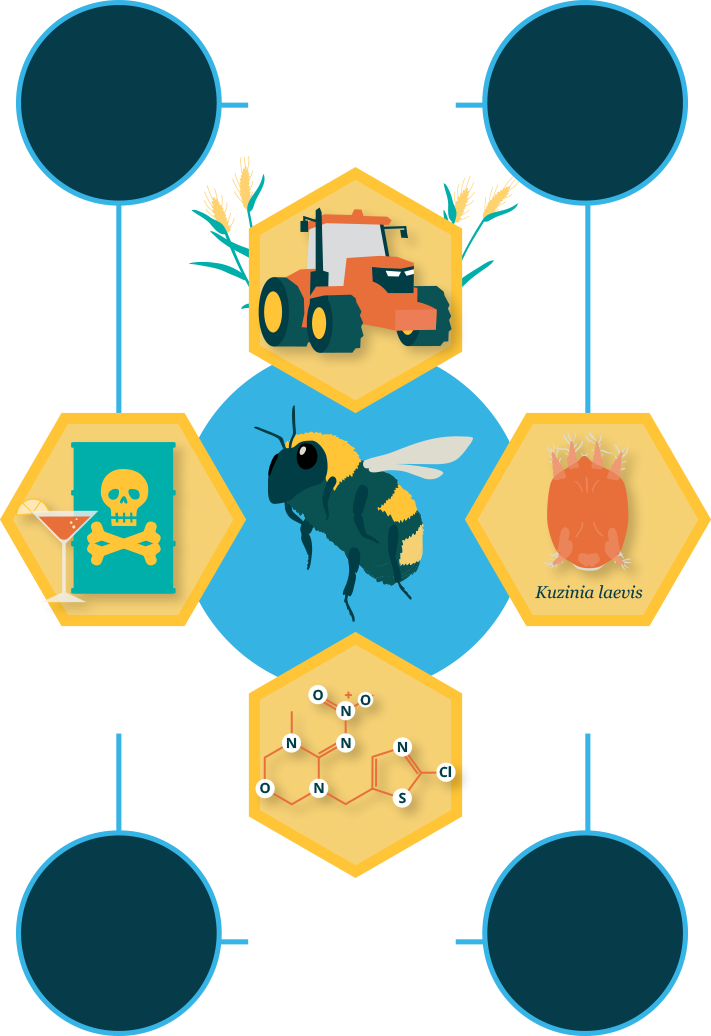

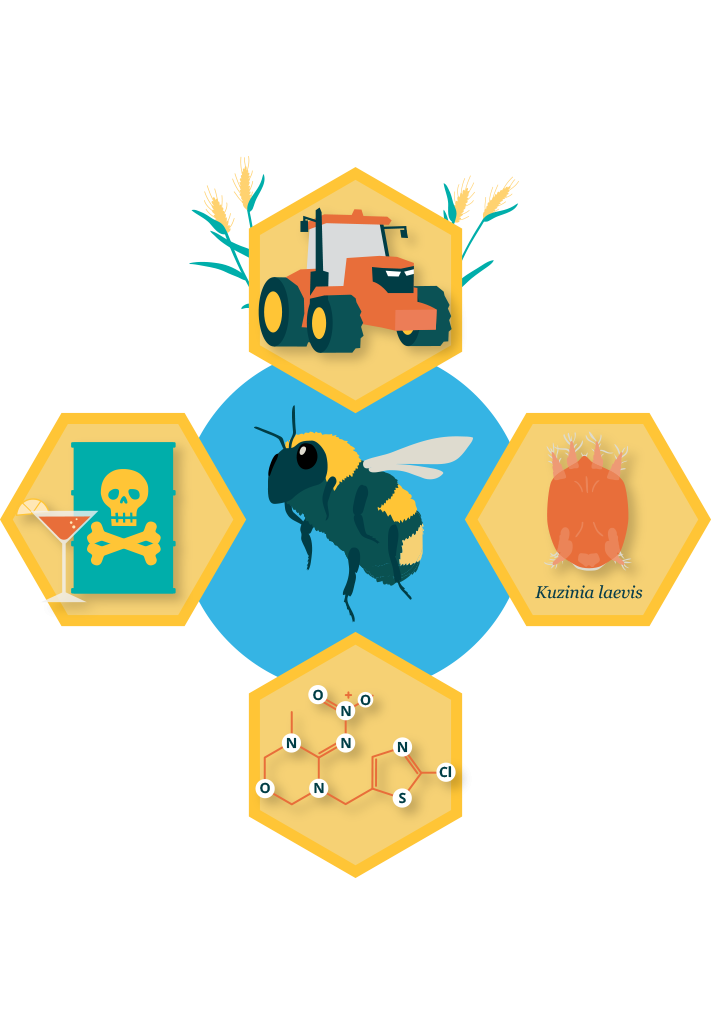

Parasites, pesticides and a lack of flowers create a deadly combination for bees¹

Monotonous diets: intensively farmed areas have few wildflowers

Cocktail of

fungicides

and insecticides

Parasites

and pathogens

Neonicotinoids

Even

wildflowers on

field verges

are often

contaminated

by pesticides

Poor diet

compromises

health & immunity

& fighting illness

uses up energy

Fungicides

can increase

the toxicity

of other

insecticides

Pesticide

exposure may

reduce tolerance

to disease

Key facts

- Even wildflowers on field verges are often contaminated by pesticides

- Poor diet compromises health & immunity & fighting illness uses up energy

- Fungicides can increase the toxicity of other insecticides

- Pesticide exposure may reduce tolerance to disease.

Reference

Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botías C, Rotheray E. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science. 2015 Mar 27; 347(6229):1255957.

- Reference

Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botías C, Rotheray E. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science. 2015 Mar 27; 347(6229):1255957.

Flowers often contaminated by pesticides

In response to criticisms on the effect of neonicotinoids on pollinators, pesticide producers and farmers often say that bee and flying insect’s exposure to pesticides is reduced by foraging on wildflowers growing on the margins of fields, which haven’t been sprayed with pesticides. However, further research by Goulson and his group in the School of Life Sciences has demonstrated that neonicotinoids applied to autumn-sown crops were contaminating the pollen and nectar of nearby wildflowers throughout the following spring and summer, sometimes at concentrations even higher than found in the crops themselves.

Having proven the clear links between the crops and nearby contamination of wildflowers, Goulson and his team next set their sights on garden flowers, which can provide important nectar and pollen to urban pollinators. They wondered whether well-meaning gardeners were doing more harm than good by buying ornamental plants from garden centres. “They’re reared in almost an industrial system in giant glasshouses,” Goulson said. To test out their hunch, they screened the leaves, pollen and nectar of flowering plants bought from major retailers in UK, such as Wyevale, Aldi, B&Q and Homebase labelled ‘bee friendly’ or ‘perfect for pollinators’ to identify plants rich in nectar to see if they were as perfect as they claimed.

Most of the plants were in fact stuffed full of insecticides and fungicides toxic to bees. 22 out of the 29 plants tested contained one insecticide and 38% had two or more insecticides. 70% contained neonicotinoid pesticides, neurotoxic insecticides used to control pests, which the European Food Safety Authority has found to pose a high ‘risk’ to wild bees and honeybees. In short, plants labelled bee friendly contained harmful chemicals which could, in fact, be killing them.

A Common Carder bumblebee (bombus pascuorum) visiting lavender. Credit: Dave Goulson

“’Perfect for Pollinators’ is the Royal Horticultural Society’s label and if you are going to label them then you should take care that it is actually perfect for pollinators and not full of insecticides,” said Goulson. “I think the retailers are guilty of being a bit lazy. They were happy to take the cash from selling the plants without being responsible about how they got hold of them.”

In response to the findings, a 2017 Horticultural Trade Association statement said neonicotinoids were only found at “low levels” on the plants. But pollen samples collected from 18 of the different plants tested contained a total of 13 different pesticides at concentrations (between 6.9 and 81 ng/g) known to cause harm to bees by impairing bee navigation and learning, reducing egg laying, lowering sperm viability, and suppressing the immune system.

Friends of the Earth used the ornamental plant research as the basis for their campaign pressuring the garden retailers into promising to sell plants reared without neonicotinoids. According to a YouGov poll 78% of the British public agreed that garden centres shouldn’t be selling plants grown with pesticides harmful to bees. The garden centres clearly took notice. By November 2017 the top 10 garden centres in the UK (including Wyevale, Hilliers, B&Q and Notcutts) had announced they would stop using neonicotinoids on garden plants in the next year, and some have already stopped using them.

Risk that neonics could be replaced by equally destructive insecticides

Despite this success, Goulson warns against overlooking the risks posed by other insecticides to pollinators. “It’s nice to feel that we have achieved something, but the attention has become very focussed on neonics. If they are just replaced by something else and the new chemicals are just as bad then we’ve achieved absolutely nothing.” Goulson plans to repeat the research on ornamental plants in a few years to find out what chemicals garden retailers are replacing them with. “There are lots of other insecticides licensed for use on ornamental flowers and new ones coming to market all the time which look suspiciously like neonicotinoids. It’s a bit depressing to be honest. I sometimes wonder if we’re making any progress.”

If [neonics] are just replaced by something else and the new chemicals are just as bad then we’ve achieved absolutely nothing.”Dave Goulson

Professor of Biology, University of Sussex

Despite the challenges, Goulson remains determined to continue his work to highlight the serious risks facing bumblebees. He’s written a series of highly readable popular science books packed full of amusing anecdotes to reach wider audiences. A Sting in the Tale, has sold over 250, 000 copies and been translated into 14 languages. His fourth book, The Garden Jungle, which explores how to foster wildlife in your garden, reached no.10 on the Sunday Times bestseller list just days after it was published and has been highly praised in The Guardian and The Times reviews.

His team is currently working with citizen scientists who are collecting data on pollinators and pesticide use in allotments and gardens in Brighton, UK and Kolkata, India in order to test and challenge government policy. “I think it’s my job. It’s my duty to hold governments to account and to keep badgering them until they do something. Scientists should be prepared to stand up when they think government has made the wrong decision, and say so. If we don’t do it, who will?”

Author: Suzanne Fisher-Murray, University of Sussex

Date published: 6 August 2019

Impacted podcast: Dave Goulson on the impact of pesticides on bumblebees

Welcome to Impacted, our new podcast series about research for real change. Listen to Dave Goulson talk about his research into the impact of pesticides on bumblebees.

Contact us

Research development enquiries:

researchexternal@sussex.ac.uk

Research impact enquiries:

rqi@sussex.ac.uk

Research governance enquiries:

rgoffice@sussex.ac.uk

Doctoral study enquiries:

doctoralschool@sussex.ac.uk

Undergraduate research enquiries:

undergraduate-research@sussex.ac.uk

General press enquiries:

press@sussex.ac.uk