Exhibition Intro ~ Map ~ Next Section

Click a thumbnail to enter the gallery. Use the arrows at either side of the image to skip forward or back.

The chequerboard landscape from Through the Looking-Glass stands out as the only Alice image not populated by people, animals or other characters (see no.15 in gallery above). It refers to an earlier art historical tradition of oak-framed landscapes in pastoral wood engravings made at the start of the nineteenth century. For instance, its form resembles one of Blake’s most celebrated wood engravings, of a blasted oak, and a comparable illustration by the medium’s most famous practitioner, Thomas Bewick. You could compare it with another landscape (no. 16), which couldn’t be more different, nor more modern. Made for the periodical Pleasant Hours, it shows the Hawaiian mountains rather than the English oak, has a portrait rather than landscape format, and an open form. Whether produced from a drawing or photograph, its style recalls photographic landscapes popular among Victorians; it might have been influenced by well-known Pre-Raphaelite paintings such as John Brett’s Val d’Aosta (1858).

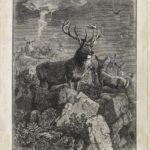

The first eight images in this section (see gallery above) draw attention to the interest in animal pictures notable in the Alice books and throughout print culture at this time. The series of images of girls and giant birds (nos. 2–6) include images from Alice, as well as from a new English translation of stories by Hans Christian Andersen (no. 5). There is an uncanny wood engraving from the magazine Good Words (no. 2), in which a girl and gull have a peculiar, symbiotic connection, and the girl stares at us with the bird’s alien gaze. Good Words was a magazine known for high quality illustrations. Curiously, some of these images anticipate a recent lithograph of a girl with a gigantic bird, Paula Rego’s Loving Bewick (2001), the title of which is a tribute to the history of wood engraving.

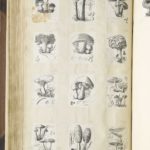

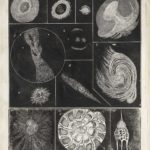

Following these, there are six images (nos. 9–14), that develop ideas from popular science or pseudo-science. This includes a detailed diagram of astonomical nebulae and marine microbiology (no. 12), and vetinerary images of calf foetuses illustrating Francis Cater’s Every Man his own Cattle Doctor (1870, no. 14); interestingly, when viewed within the Dalziel’s proof albums instead of in the published books, such images become notable for their beautiful and disturbing artistic qualities, rather than their scientific use. Alongside them, images from Through the Looking Glass (nos. 10 & 13) make jokes about whimsical species of insect like the ‘Rocking-horse-fly’.

Finally, images 15–23 explore plants and landscapes, with works after Pre-Raphaelite painters Ford Madox Brown and Arthur Hughes, for books including Christina Rossetti’s Sing-Song (published in 1872, although the blocks were engraved in 1871).

Bethan Stevens

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW4-20_p132.jpg-detail-1-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘The Queen's Croquet-Ground’, Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW6-20_p136.jpg-detail-3-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘The Pool of Tears’, Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW8-20_p132.jpg-detail-3-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Looking-glass insects’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW10-28_p151.jpg-detail-2-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Looking-glass insects’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW13-28_p151.jpg-detail-3-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘The Garden of Live Flowers’, Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW15-28_p150.jpg-detail-5-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘The Garden of Live Flowers’, Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW18-28_p152.jpg-detail-1-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Pig and Pepper’, Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NW21-20_p135.jpg-detail-6-150x150.jpg)