Exhibition Intro ~ Map ~ Next Section

Click a thumbnail to enter the gallery. Use the arrows at either side of the image to skip forward or back.

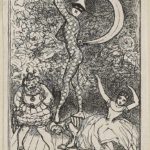

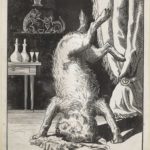

Both Lewis Carroll’s Alice books are fascinated by acts of performance and the way these integrate with normal social life and children’s play. The Mad Hatter’s tea party offers no sustenance in the way of food and drink; it re-enacts and parodies an everyday ritual, in the process making it marvellous. In both the Alice books, characters frequently break into song or dance. These are not straightforward celebrations of performance; often, they bore Alice terribly. And some of the performances only happen because of threats by a despotic monarch. At the beginning and end of both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, we witness Alice at play in a realist setting. Her manipulations of toys and banal objects can be seen as theatre that she directs.

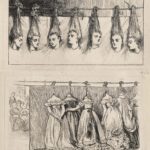

For middle-class Victorians, amateur performance was a common home entertainment, and the lines between performance and play were blurred for both children and adults. Many examples are shown in this section (see gallery above). The following text was published with the second image in this section, illustrations that instruct readers in staging a tableau vivant of the fairytale ‘Bluebeard’. The text is from a Christmas edition of Warne’s Home Annual:

The Blue Beard Tableau

This effective tableau is very easily arranged. A room with folding doors is best, as the framework of the doors forms an excellent frame for the picture. […] The door is opened wide, and the ghastly picture unveiled to the spectators. The heads of seven young and beautiful women are seen suspended by the hair from the ceiling, each face wearing an expression of its own which the artist has happily portrayed. The picture only shows the heads, but as a matter of course, in the tableau itself, Fatima is seen in the foreground, cowering with horror.

The next picture shows the expedient resorted to in order to conceal the bodies, which are supposed to be severed from the heads. A piece of white muslin is stretched across the background; the heads of the actors are thrust through this screen, and the loose hair is fixed to a roped suspended from hooks above. In this manner the bodies are effectively hidden by the cloth, and the optical delusion is complete. A piano accompaniment from the opera of Barbe Bleue may be appropriately played during the tableau. Other scenes from the story may be added with good effect. (Laura Valentine, ed., Warne’s Home Annual, 1868).

Bethan Stevens

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for 'A Mad Tea Party', in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP3-20_p137.jpg-detail-3-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for 'The Lobster Quadrille', in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP6-20_p137.jpg-detail-7-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘A Mad Tea-Party’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP8-20_p137.jpg-detail-4-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Humpty Dumpty’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP10-28_p152.jpg-detail-5-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP12-28_p153.jpg-detail-6-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Who Stole the Tarts?’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PB-15-20_p140-1.jpg-1-1-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Which Dreamed It?’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP14-28_p155.jpg-detail-5-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Looking-Glass House’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP16-28_p150.jpg-detail-8-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for ‘Tweedledum and Tweedledee’, in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PP18-28_p152.jpg-detail-6-150x150.jpg)