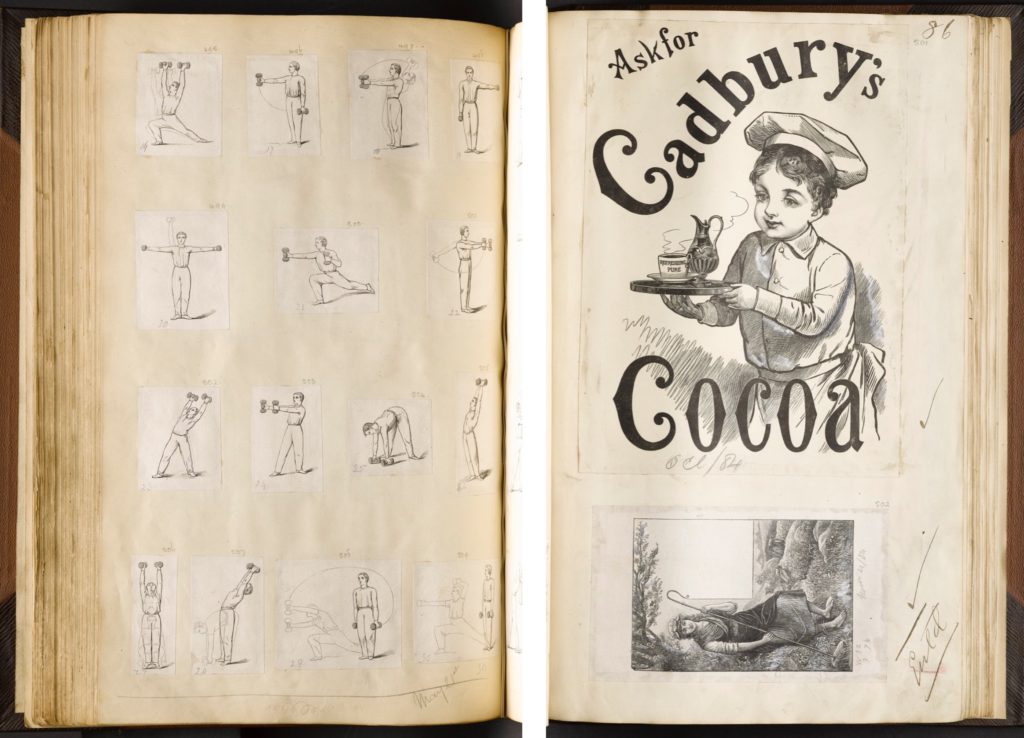

In Victorian London, ‘woodpeckers’ or ‘peckers’ was slang for wood engravers. At this time, wood engraving was the medium of mass production, profusely illustrating books, magazines, catalogues and packaging: everything from Dickens and Trollope illustrations to fitness manuals and chocolate adverts. Wood engraving was ubiquitous, not unlike the digital photograph today, but far more labour intensive.

Dalziel Brothers was the most substantial London wood engraving firm. George Dalziel (1815–1902) was the first of the family to move from Northumberland to London, travelling down by sailing ship in 1835. In 1839, his brother Edward (1817–1905) joined him. They worked together for over fifty years, maintaining a successful business through the many technologicial, cultural and commercial changes of the century. They were joined in the 1850s by their brothers John and Thomas, and their sister Margaret, also important as a woman working in a male-dominated industry. In addition, there were many employees in the wood engraving factory. In their 1901 memoir, the Dalziels particularly remembered Francis Fricker and James Clark, who worked for them for over forty years. All employees signed their work ‘Dalziel’, so in most cases we do not know who engraved individual images, but this is a research question being investigated by this project.

The Dalziel Archive in the British Museum is a visual archive of the firm’s oeuvre from 1839 to 1893: around 54,000 fine burnished proofs kept chronologically in albums. The albums offer a new path into 19th-century wood engravings, usually approached exclusively through designers or the texts that they illustrated. They reveal fabulous works of visual art that have remained hidden (e.g. because they were stuck in failed literary works), and create new contexts for the illustrations, as fine art and elite poetry jostle alongside technical diagrams, and scientific illustrations of molluscs or parasites. The Dalziels had enormous cultural power at a key moment in history, shaping the way people visualised things. They produced landmark images, including all the illustrations to Lewis Carroll’s Alice books of 1865 and 1871 as well as numerous pre-Raphaelite illustrations to Edward Moxon’s landmark edition of Tennyson’s Poems (1857). Mostly the Dalziels engraved images after designs by draughtsmen, including household names such as John Tenniel, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, Arthur Hughes and Frederic Leighton, and it is these who have been widely credited as authors of what were fundamentally collaborative productions.

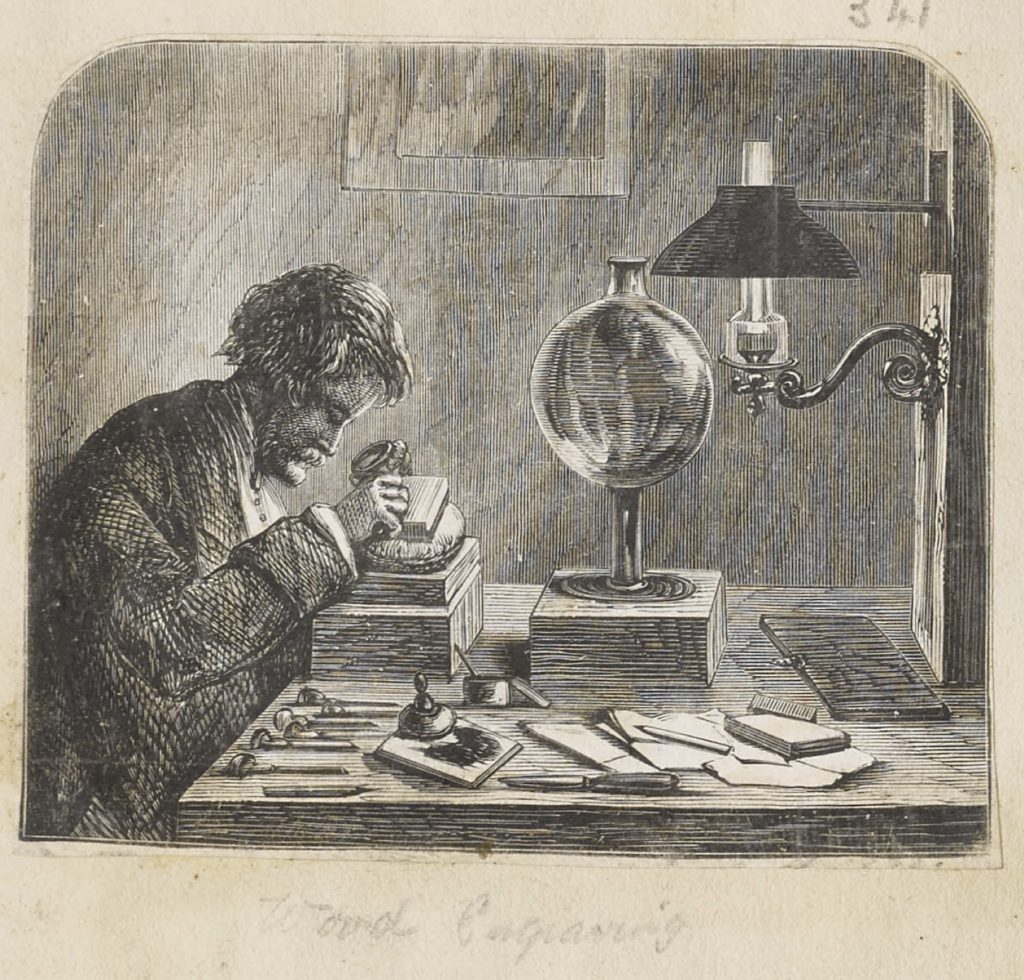

The technique of wood engraving was revived and developed in the early 19th century, revolutionising the mass production of images. It was different from the earlier woodcut; cut on boxwood (an extremely hard wood), and using the endgrain rather than the plank, it was capable of much finer detail, so fine that it could compete technically with copper and steel engravings. Furthermore, wood engravings were far cheaper to print than copper or steel, since the latter required a separate printing process, whereas wood engravings could be printed letterpress with type. These innovations meant that wood engraving, like no other visual medium in the Victorian period, was capable of extraordinary detail combined with cheap mass production. In the last decades of the century, wood engraving was replaced by photomechanical techniques, such as the line block and half-tone. This eventually put Dalziel out of business in 1893.

The technique of wood engraving was revived and developed in the early 19th century, revolutionising the mass production of images. It was different from the earlier woodcut; cut on boxwood (an extremely hard wood), and using the endgrain rather than the plank, it was capable of much finer detail, so fine that it could compete technically with copper and steel engravings. Furthermore, wood engravings were far cheaper to print than copper or steel, since the latter required a separate printing process, whereas wood engravings could be printed letterpress with type. These innovations meant that wood engraving, like no other visual medium in the Victorian period, was capable of extraordinary detail combined with cheap mass production. In the last decades of the century, wood engraving was replaced by photomechanical techniques, such as the line block and half-tone. This eventually put Dalziel out of business in 1893.

Bethan Stevens

In association with: