Exhibition Intro ~ Map ~ Next section

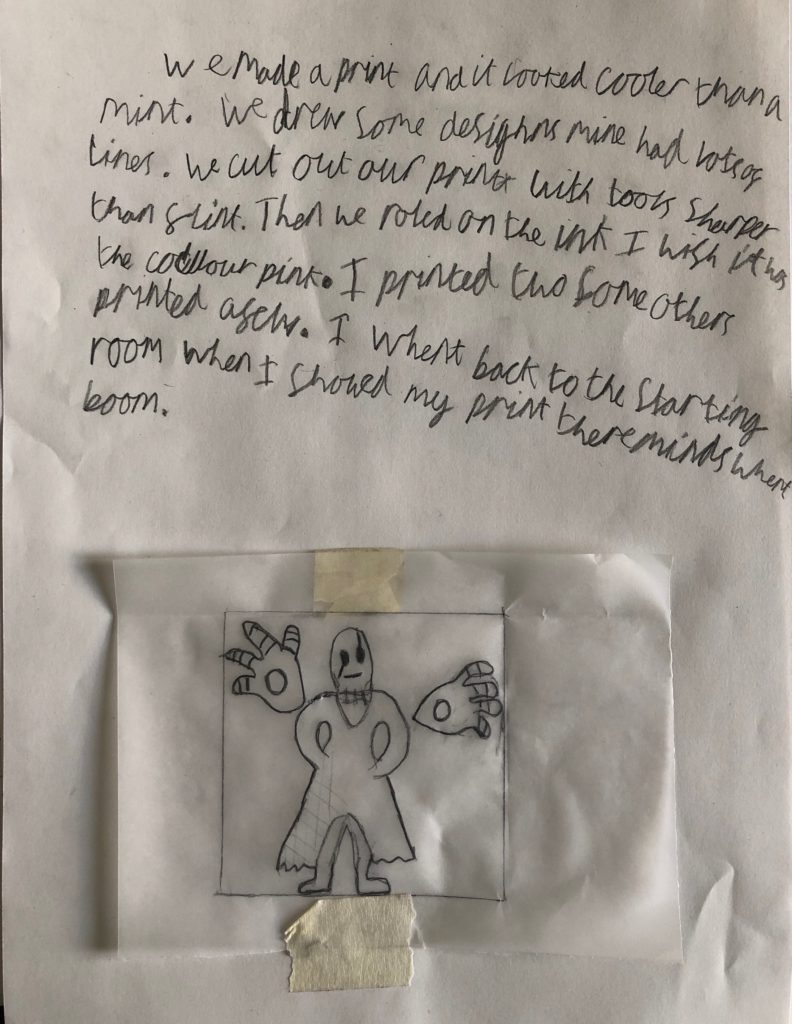

“We made a print and it looked cooler than a mint.

We drew some designs mine had lots of lines.

We cut out our prints with tools sharper than flint.

Then we rolled on the ink I wish it was the colour pink.

I printed two some others printed a few.

I went back to the starting room

When I showed my print their minds went boom.”

This student’s poem describes excitement of creating a linocut print. The printmaking workshop, described at the end of this section, invited students to imagine the experience of Victorian printmaking apprentices, like the young employees who made wood engravings for Dalziel. Printmaking was one of a set of strategies through which they could empathise with the experiences of people in the nineteenth century. Reading and creative writing provided further opportunities for identification and empathy.

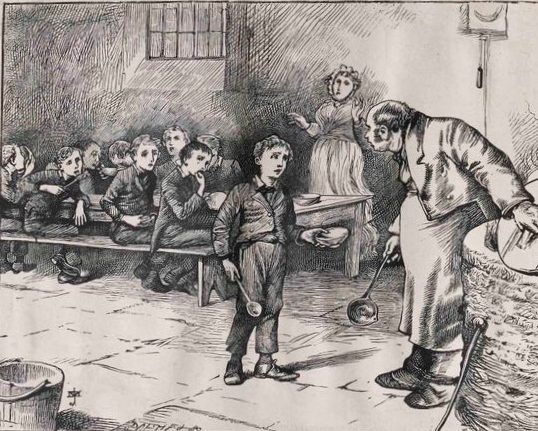

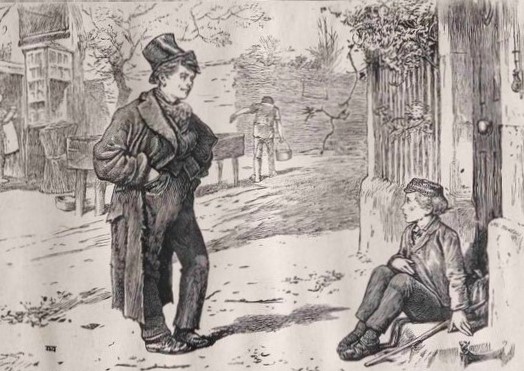

Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist has been critiqued and reimagined many times. BACA students had already read and discussed this book as part of their coursework. Oliver’s adventures are well known: his persecution in the workhouse after he asks Mr Bumble, the Beadle, for more gruel (illustrated above), his escape from his apprenticeship with the undertaker Mr. Sowerberry and his long walk to London where he meets the young pickpocket known as “The Artful Dodger” (see below), who introduces him to a criminal gang before he finally discovers his ancestry and inheritance. The story was originally serialised between 1837 and 1839 in the periodical Bentley’s Miscellany with illustrations by George Cruikshank. The Dalziel Brothers produced wood engraved illustrations after J. Mahoney for a new edition published by Chapman and Hall in 1871 examples of which are shown in this section. When students visited The Keep they were able to compare the two editions.

The story often concerns the experiences of young people including the children in the workhouse, apprentices and the pickpockets. Therefore, BACA students were able to compare their lives today with those of their fictional counterparts in the nineteenth century. Here, they discuss how the Dalziel illustrations add emotional charge to the narrative.

A student considered how composition and lighting dramatize the pivotal moment in Oliver’s story when he “asks for more” while another recognised Dickens’s critique of the treatment of children in the workhouse.

“It is very detailed with shading in the top left and how the light in the centre is shining on Oliver.”

[The] “Please Sir image .. tells us that childhood in the workhouse drives the children to go to the point of death. Oliver is so desperate that he has to fill his tiny bowl with gruel in the mouldy food pot.”

Two students considered how the illustrations conveyed the drama of a harrowing scene later in the book. Here, a member of the gang, Bill Sikes, has killed his mistress, Nancy, after she had taken pity on Oliver. They considered how the illustration is composed for emotional effect and discussed their own reactions.

[The] “Scene makes itself look shady because the light is shining through the window on to the corpse and Bill is dragging the dog out showing that his dog does not want to leave Nancy”

“The way the shade [falls] on the floor is dramatic. You can barely see Bill and his dog in the shadow. This shows Bill has done something bad to Nancy.”

One student developed the themes of a violent and controlling relationship in a poem which echoes this representation of Nancy’s murder:

“Sorrow, selfishness regret

She was suffering

While he was sitting in self pride

She was over him

Whilst he could not care less

She had her life to lose

Whilst he would not lose.

Realisation, guilt regret

She left the man

Whilst he begged her to stay

She ran away while he talked to chase her

She would not forgive

Whilst he said sorry every day

Broken, lifeless regret

She lay there still

Whilst he stood there

Far from distilled

She was colourless

Whilst he was selfless

She was gunned down

Whilst he let everything hear the sound.”

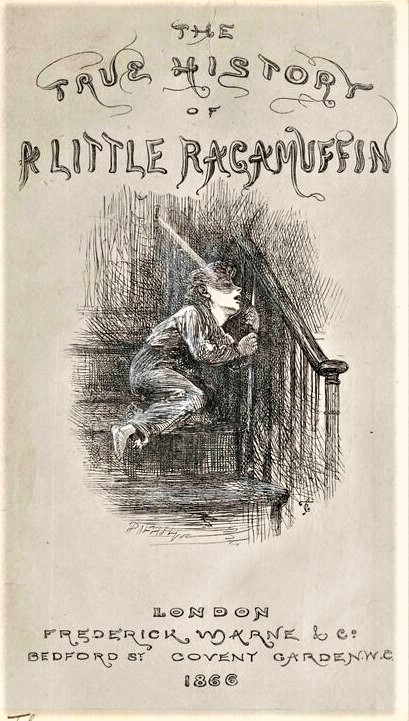

Tales of child poverty, labour and criminality provided dramatic content, pathos and social comment for many Victorian writers, as suggested by the Dalziel illustrations, after JC Thomson, to James Greenwood’s The True History of a Little Ragamuffin (1866). Meanwhile, orphaned children or those from broken homes remained central figures in Victorian literature. However, one theme of Oliver Twist is that of a young person finding their identity in the world, a subject that Dickens explored in his later novels David Copperfield (1849-1850) and Great Expectations (1860-1861). These aspects of Dickens’s writing were underpinned by an interest in apprenticeship, learning and rites of passage.

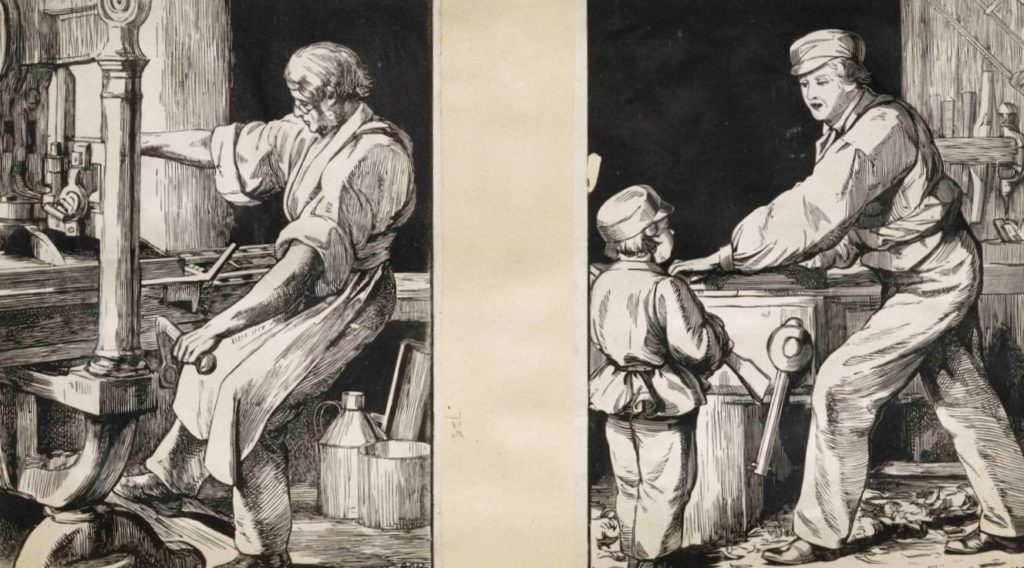

Reading, researching, writing and making were all processes by which students could explore different identities and value their individual responses to the material. By creating linocuts they were able actively connect with a process of printmaking comparable to the wood engraving used in nineteenth-century illustrations. Indeed, AW Bayes’ illustrations from 1865 which show craft practices and young people observing them (above) are echoed in photographs of the BACA printmaking workshop at the University of Sussex:

Student contributors: Alicia, Alisha, Cerys, Gordon, Jake, Lillian, Lucie-Lee, Nianna, Reuben, Robert, Rose, Sam, Sonny, Tamia, Thai.