Stevenson Lecture Theatre, British Museum

Friday 16th June – Saturday 17th June 2017

Register here

Generously supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Museum and the University of Sussex.

Contributors

Caroline Arscott (Courtauld), Geoff Belknap (University of Leicester), Neil Bousfield (Norwich University of the Arts), Laurel Brake (Birkbeck), Luisa Calè (Birkbeck), Esther Chadwick (British Museum), Douglas Downing (Independant Scholar), Hannah Field (Sussex), Michael Goodman (Cardiff), Georgina Grant (Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust), Natalie Hume (Courtauld), Lorraine Janzen Kooistra (Ryerson), Peter Lawrence (Society of Wood Engravers), Brian Maidment (Liverpool John Moores), Katharine Martin (V&A), Susan Matthews (Roehampton), George Mind (Sussex), Felicity Myrone (British Library), Tom Mole (Edinburgh), Sheila O’Connell (British Museum), Clare Pettitt (Kings), Isabel Seligman (British Museum), David Skilton (Cardiff), Lindsay Smith (Sussex), Bethan Stevens (Sussex), Julia Thomas (Cardiff), Mark Turner (Kings) and Kiera Vaclavik (Queen Mary).

Timetable

Friday 16th June

9.30 Coffee & pastries

9.45 Welcome

10.00

Panel 1: Periodicals and Draughtsmen

- Brian Maidment (Liverpool John Moores), Graphic humour, the wood engraving and the periodical press before Punch

- Natalie Hume (Courtauld), Graphic America

- David Skilton (Cardiff), Millais’s pictorial capitals to The Small House at Allington

11.30

Dalziel Archive Introduction

- Bethan Stevens (University of Sussex), The Story of the Dalziel Archive, 1839-1893

- Peter Lawrence (Society of Wood Engravers), response

12.30 Lunch

13.20

Panel 2: Technology and Materiality

- Georgina Grant (Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust), Uncovering the Coalbrookdale Company catalogueS: the artistry of Victorian wood engravers

- Hannah Field (University of Sussex), Our Peepshow: Surface, Depth, and Touch in Victorian Pop-up Books for Children

14.20

Dalziel Archive Volume 1, 1839-1848

- Julia Thomas (Cardiff University), Affillustration: the Dalziel Digital Network

- Susan Matthews (Roehampton University), response

15.20 Tea break

15.40

Panel 3: Illustration and Re-Vision

- Tom Mole (University of Edinburgh), Retro-Fitted Illustrations and Victorian Modernity

- Luisa Calè (Birkbeck, University of London), The Dalziels’ Bible Gallery: Portfolio, Album, Bible in Pictures

- Kiera Vaclavik (Queen Mary, University of London) The Forgotten Alice Artists of the Nineteenth Century

17.10 – 18.30

Viewing of Dalziel Archive and related material in the Prints and Drawings Study room

Saturday 17th June

9.20

Panel 4: Drawing and Writing

- Lindsay Smith (University of Sussex), ‘Awful lines’: Ruskin writing on drawing, engraving and daguerreotyping

- Isabel Seligman (British Museum), The executioner’s accomplice: capital losses and vital gains in the work of Victor Hugo

10.20 Coffee and pastries

10.35

Dalziel Archive Volume 20, 1865

- Clare Pettitt and Mark Turner (King’s College London), What is an Album?

- Sheila O’Connell (British Museum), response

11.35

Panel 5: Technology and Science

- Esther Chadwick (British Museum), The Work of Wood-Engraving in a Photomechancial Age

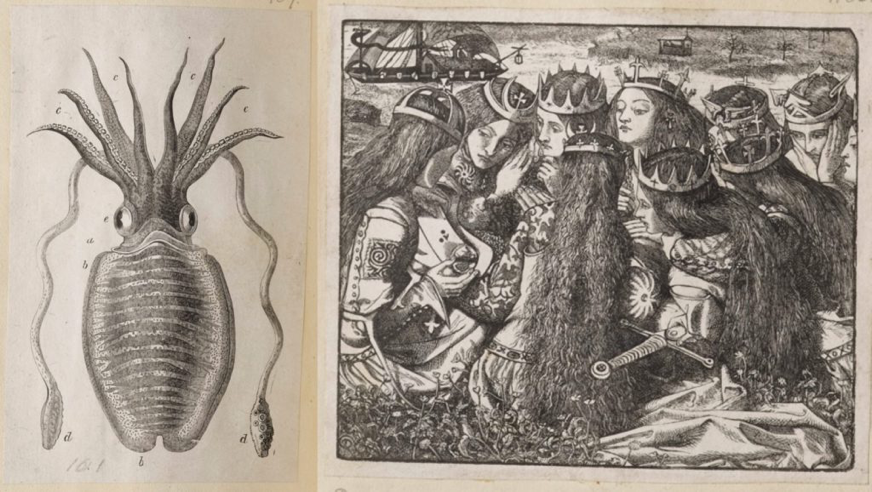

- Geoff Belknap (University of Leicester), Participating in Victorian Natural History through the Illustrated Periodical

12.30

Lunch, with viewing of Dalziel Archive and related material in the Prints and Drawings Study room

13.40

Dalziel Archive Volume 26, 1869-70

- Lorraine Janzen Kooistra (Ryerson University), Reading a Grammar of Ornament in the Dalziels’ Proofs Book Volume 26 (1869-70)

- Felicity Myrone (British Library), response

14.40 Tea break

14.50

Panel 6: Re-Imaginings

- George Mind (University of Sussex), Contemporary Re-imaginings of The Dalziels

- Douglas Downing (Independent Scholar), Pictures in the Fire or Great Uncle George Dalziel, discovering a long-lost family history

- Neil Bousfield (Norwich University of the Arts), Archive, narrative and the construct of place

16.15-17.15

Round Table

TBC, participants include: Caroline Arscott (Courtauld), Michael Goodman (Cardiff) and Katherine Martin (V&A).

Abstracts

Geoff Belknap

University of Leicester

Participating in Victorian Natural History through the Illustrated Periodical

The practice of illustrating Victorian natural history periodicals was widespread throughout the century. Yet the value, meaning and intent of these illustrations as objects of scientific evidence within an essential site of scientific communication is little understood. Focusing on the genre of the natural history journal between 1840-1890, this talk will evaluate the role of illustrations in offering an access point for the amateur naturalists to participate within the knowledge community of the Victorian periodical. A key aspect in this analysis will be to differentiate between authors and readers of competing periodicals in order to evaluate whether there is an overlap between contributors and consumers of the Victorian periodical. In this way, this paper will pay particular attention to the category of the non-professional author and illustrator in order to better understand the role of the periodical in giving access to a wide audience to the sites of production and reproduction of nineteenth-century natural history.

Neil Bousfield

Norwich University of the Arts

Archive, narrative and the construct of place

Historical event, narrative and collective memories are documented, held and imparted within objects, artefacts, archives and things. The narratives we hold and discover inform the memories and experiences that construct a sense of place.

Where we live and who we are is inextricably bound to and encompassed within the notion of home and place and the concepts of place identity and place attachment. This paper examines current practice-based research to explore the relationship between contemporary engraving practice, historical artefacts and archives within the emotional construct of place. A discussion is advanced through an understanding of memory, narrative, emotion and place and an argument is presented for archives as “sites of knowledge production.”

Archives and historic artefacts are reinterpreted, not as sites for information retrieved, but as repositories of memory and narrative to be re-remembered within practice-based research in order to map unseen landscapes.

The image is seen and read through the experiences and identity of an engraver residing by the sea. Hence the significance of the engraved artefact and its ability to be repurposed, represented and reimagined within the context of a contemporary engraving practice in order to integrate the notion of place and identity, and this idea shapes the discussion and the focus of the paper.

Key words: narrative, place, memory, place identity, place attachment, engraving, archives, archival prints

Luisa Calè

Birkbeck, University of London

The Dalziels’ Bible Gallery: Portfolio, Album, Bible in Pictures

Must a collector retain intact and whole a set of an illustrated periodical for the sake of a few dozen pictures within it, or if he decides to tear them out, will he not be imitating the execrable John Bagford, who destroyed 25,000 volumes for the sake of their title-pages? Must he mutilate a Tennyson’s Poems (Moxon 1857) for the sake of arranging them in orderly fashion?’ (Gleeson White, 1897)

Gleeson White’s address to collectors highlights the ephemeral dynamic of print in the paper archive. While imperfect sets of illustrated periodicals were most likely to be cut up for the pictures, recycled in the paper mill, or consigned to the flames, the divorce of prints from their textual accompaniments could be extended to deluxe editions. The desire to isolate the illustrations was captured by commercial initiatives such as The Cornhill Gallery. Reflecting on the paper gallery as a genre of reproductive engravings, going back to Thomas Macklin’s Bible, I will concentrate on the Dalziels’ Bible Gallery, which was initially planned as an illustrated Bible in 1863, but eventually published as a portfolio of engravings in 1880. As was the firm’s custom, a specimen of the set of engravings was inserted in album 62 as a record of their practice; however since the Dalziel albums were acquired by the British Museum, this set was disbound and the plates were rearranged in Solander boxes under the name of the artist. I will explore how the Bible Gallery negotiates the distinction between illustration and separate plate, the medium of the book and the gallery of pictures, reflecting on the ways of seeing and reading supported by the original publication and the competing logics and divisions of knowledge that govern its inscription in the paper archive.

Esther Chadwick

British Museum

The Work of Wood-Engraving in a Photomechancial Age

This paper will address the role of photographic processes in the Dalziels’ wood-engraving practice, based primarily on evidence in the BM archive. It will take as its starting point a wood-engraving made in 1865 for Ralph and Chandos Temple’s anecdotes of ‘Invention and Discovery’ (in Dalziel Volume XIX) showing the process of so-called ‘photo-sculpture,’ which involved pantographic transcription in three dimensions of a screen image projected from multiple photographs of an object or person. The point will be to think about the Dalziels’ work in the context of nineteenth-century innovations in image transfer, re-scaling, and replication, and to consider the coexistence and interaction of various different graphic techniques, as well as to better understand the Dalziels’ own attitudes towards new photographic technologies. What exactly were the photomechanical ‘process’ prints that start to enter the final volumes of their archive in the 1880s? And what impact did photography have, ultimately, on their business and the wood-engraving with which they had become synonymous?

Douglas Downing

Independent Scholar

Pictures in the Fire, or: Great Uncle George Dalziel, discovering a long lost family history

As a child Douglas Downing liked nothing more than looking through the old family photographs and piecing together the family history. It was thanks to his grandparents that storytelling was a common occurrence, as they often recounted stories about their life in east London during the Second World War, or going to school in the shadow of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Douglas was perhaps destined to become the family historian. And in some way, it was these early experiences in genealogy which fired his imagination working in film and television production.

It was several years later with the internet at his fingertips that he started to search for the names and dates of his ancestors, but he wasn’t expecting what came next! When he first came across the unusual surname Dalziel, at that time it was only another name to add to the list, but on further exploration a different story revealed itself, one which was rich in social and art history but ultimately told an everyday human interest story of life, home and family in 19th century Britain.

Douglas’ talk is a culmination of 11 years worth of research and like any good story there is always a prequel. So to enliven the Dalziel story he unlocked the door and brushed off the dust and immersed himself in the archives. He started to look at the Dalziel family in 19th century Northumberland and how it all began, tracing the family footsteps. By doing this Douglas started to uncover some remarkable stories about the origins of the Brothers Dalziel; along the way he has created some new stories, and this is what he will discuss with you during his talk.

Hannah Field

University of Sussex

Our Peepshow: Surface, Depth, and Touch in Victorian Pop-up Books for Children

As part of his career-long commitment to exploring the aesthetics of childhood, Walter Benjamin proposed that children have a distinctive relationship to the illusion of surface and depth in pictures. ‘Their eyes,’ he wrote around 1914, ‘are not concerned with three-dimensionality; this they perceive through their sense of touch.’ This paper uses the Victorian pop-up book, in which a sequence of cut-out layers affixed to a page springs out to make a three-dimensional image, to materialize Benjamin’s enigmatic statement. The pop-up book’s three-dimensionality is at once illusionary and tactile: reliant on an image that uses established visual rules for representing depth, but also offering actual three-dimensionality produced by the reader’s physical manipulation of the book. As such, the form raises a number of questions. How does the nineteenth-century preoccupation with regulating perspective and depth of field play out within the children’s pop-up—and how does it relate to conceptions of children’s literature as a controlling apparatus? How does the lo-fi, literal three-dimensionality of the pop-up relate to other Victorian modes of 3-D image-making, for instance, the haptic quality of stereoscopic pictures, theorized by Jonathan Crary and David Trotter (among others)? And how might the ‘minor depths’ of style and subject in the children’s pop-up encourage fresh understandings of the book itself, a three-dimensional object that is consistently imagined in terms of its flat metonym—the page? The picture book for children, now in 3-D.

Georgina Grant

Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust

Uncovering The Coalbrookdale Company Catalogues: The Artistry of Victorian Wood Engravers

The Coalbrookdale Company of Shropshire, England, was founded in 1709 and was famed for its cast iron work. In the 1840s, the Company began developing lines of decorative cast iron products. To advertise these wares, the Company produced illustrated catalogues. By the middle of the nineteenth century, these catalogues had become commonplace, and manufacturers and retailers were shrewd to advertise their products as desirable commodities. The Coalbrookdale Company reached their zenith with a magnificent catalogue in 1875, which consisted of two volumes totalling over one thousand pages. Some items, such as gates and railings, fireplaces or kitchen ranges, were available with literally hundreds of different designs to choose from.

A number of now almost forgotten Victorian wood engravers illustrated these catalogues, which were rendered with the same respect and accuracy as any piece of fine art.

Eight years ago, Aga Rayburn, which sits on the former site of the Coalbrookdale Company foundry, donated a collection of nineteenth century printing blocks to the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. There are around one thousand blocks, each of which was used to illustrate the Coalbrookdale Company catalogues. With the help of volunteers, the blocks are being cleaned, catalogued and researched.

This talk will uncover the journey of the 1875 Coalbrookdale Company catalogue, from the designers, engravers, and printers to the final products produced in the foundry. Catalogues can be viewed as part of a larger process of mass consumption and aesthetic taste in the nineteenth century, which this talk will also explore, alongside the less-known lives of their engravers.

Natalie Hume

The Courtauld Institute of Art

Woodpeckings: Graphic America

This paper examines the Graphic America series as a unique and ambitious experiment in pictorial journalism, and proposes that, despite the illustrations’ striking, distinctive visual style and avuncular commentary, they were overwhelmingly preoccupied with fragmentation, disorientation and occlusion.

In autumn 1869, following the completion of the United States transcontinental railway that summer, William Luson Thomas sent Arthur Boyd Houghton across the Atlantic. The artist was to gather visual material on everyday American life for Thomas’s new illustrated paper the Graphic, which would launch in December as a direct rival to the Illustrated London News. Houghton’s trip resulted in a sequence of nearly eighty images with text, published over a period of three years. Houghton travelled westwards from the metropolitan centres of New York and Boston, visiting farms, Native American villages, and religious settlements. Everywhere he focused on closely observed social detail, with particular interest in public spaces and communities.

The illustrations have an unusual, autographic look, a result of editorial production decisions as well as of the artist’s practice of sketching directly onto boxwood plates. They tend to be asymmetrical, with expanses of white punctuated by heavily inked, textured areas; others are very dark with a range of shading techniques that produce a layered, woven effect. In tone, the pictures oscillate between humour and horror, caricature and the grotesque, with occasional moments of beauty.

Lorraine Janzen Kooistra

Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada

Reading a Grammar of Ornament in the Dalziels’ Proofs Book Volume 26 (1869-70)

“We take patterns too much for granted,” Joan Evans observed in Style in Ornament (1950). “We should learn to plunge our minds into them, as we do into the sea of poetry, and to receive as sharp an impression of an age from its ornament, as we do from its literature.” Evans’s directive comes nearly a century after the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the monumental historical source book that came out of it, Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament (1856), both of which informed an increasingly ornamental turn in Victorian culture. While many critics have investigated the intersection of art and industry in the decorative arts in the second half of the nineteenth century, less attention has been paid to the presence of textual ornaments in the period’s illustrated periodicals. In this paper, I plunge my mind into the patterns of ornament that decorated the pages of Good Words, Good Words for the Young, Sunday Magazine, and St Paul’s between 1869 and 1870. Volume 26 of the Dalziel Brothers’ Proofs’ books, which is made up entirely of wood-engravings for these magazines, allows me to read the pictorial letters, decorative borders, symbolic emblems, and ornamental templates without the “noise” of letterpress and distraction of verbal content. Concentrating on ornamental types and genres to the exclusion of illustrative cuts, I consider how decorative pattern might have engaged the middle-class readers of these popular magazines. Taking as “sharp an impression” as I can from the Dalziel Brothers’ impressions of wood-engraved textual ornaments, I argue that the decorative patterns of repetition and difference helped Victorians navigate an increasingly complex world of print by building a common visual vocabulary with links to both an assumed cultural heritage and a transnational world of modular design.

Brian Maidment

Liverpool John Moores University

Graphic humour, the wood engraving and the periodical press before Punch

This paper offers a broad if brief overview of the key developments in the use of the wood engraving as a comic and satirical medium within the periodical press in the twenty years before the founding of Punch in 1841. In particular, it considers the relationships between the continuing tradition of political and social satire, the development of new forms of diversionary graphic humour, and the emergence of caricature and comic art as a form of social reportage. It suggests the various strategies that magazines used to locate the comic wood engraving within large and visually complex pages and the ways in which the vignette form was adapted for use in periodicals. The importation of images into the periodical press from previous publications will also be discussed, as well as the ways in which magazine editors and publishers developed ways of reprinting illustrations from magazines as separate publications, thus suggesting the commercial potential and graphic potential of the blocks used for producing comic images. Bell’s Life in London, Figaro in London, The Comic Magazine and the innovative publications of C.J.Grant will all feature in the discussion, which will suggest the extent to which Punch was formulated as a clever anthology of contemporary humorous illustrative practices.

George Mind

University of Sussex

Contemporary Re-imaginings of The Dalziels

We live in a culture troubled by the “pandemonium of Image,” to borrow a line from Derek Jarman’s Blue, a film that offers viewers (somewhere amidst its devastating contents) respite from the seemingly inescapable chaos of the visual. For seventy-five minutes, the viewer is bathed in a static shot of blue, sharing in Jarman’s experience of blindness. The Dalziel Brothers recorded the origins of this pandemonium: their forty-nine albums documenting the burgeoning of an image-saturated world.

In this presentation, I will consider how the Dalziel Archive speaks to our contemporary moment. These albums of Victorian illustration compel us to scrutinise current preoccupations with acceleration, automation, mediation, and collaboration. Moreover, they agitate tensions between the material and digital. To illustrate these ideas, I will introduce some of the exceptional creative responses produced over the past year by participants of the Dalziel Project public and educational programme.

By their nature, the Dalziel albums resist our contemporary compartmentalising of learning. One can only approach this material in an interdisciplinary way. The albums are demanding objects: those that engage with them must perform intellectual acrobatics, employing scientific and historical knowledge, spatial understanding, and imaginative reconstruction to make sense of them, to figure them in terms of the commonplace, and the surreal. In this way, the Dalziel albums stimulate new, hybrid modes of creative response.

Tom Mole

University of Edinburgh

Retro-Fitted Illustrations and Victorian Modernity

When Victorian readers encountered Romantic-period writings, they were not usually reading Romantic-period books. Instead, they mostly encountered Romantic writing in new editions, which supplied existing works with a new bibliographical format. Retro-fitting Romantic works with illustrations offered a way to naturalise them in the new media ecology and renovate them for a new generation of cultural consumers. Victorian commentators often identified illustrated books as a characteristically modern phenomenon. When the publisher Robert Cadell claimed in 1844 that his was ‘the age of graphically illustrated Books’, he reflected a widespread understanding among publishers and booksellers that the new popularity of book illustration had recently made illustrations a virtual necessity for commercial success. This paper will argue that many Victorians thought that the progress of book illustration was another manifestation of the generational shift that separated them from the Romantic period. They insisted not only that illustrated books were characteristic of the current moment, but also that their quality was one of the things that set that moment apart from the preceding age. I conclude that illustrations were often credited with the power to renew texts from the past and make them newly attractive in the present.

Clare Pettitt and Mark Turner

Kings College, London

What is an Album?

This paper will show and describe the Dalziel Brothers’ album for the year 1865, extrapolating an epistemology of form through a close interrogation of the particularity of the object itself. Then we will consider the series to which this album belongs in order to situate the whole series of Dalziel albums alongside other forms of temporal reckoning with print.

We will present our approach by first testing the 1865 album against other contemporary ‘forms’: the annual, which ‘sums up’ a year; the scrapbook which acts as a record of individual creativity and a repository of memory; the photograph album, which, in the 1860s, displays technology as much as photographic images themselves; and the business ledger, which was increasingly available ready-printed in standardized forms in the 1860s. We will consider these other forms of gathering, cataloguing, indexing, and representing print/image/information in timed sequence. We will note significant differences between the Dalziel album (the lack of rigor in the formal cataloguing, etc.) and argue for it as an expressive, sometimes contradictory, memory object of both individual engraver-artists and a firm.

We will then think about the 1865 album as part of a series and investigate the ways in which it both represents and helps to sustain the dominant rhythm of seriality not only on an annual scale, but in weekly, monthly and seasonal iterations too. We will consider the ways in which some of the contents of the 1865 album might help us think about print and seriality: the proofs pasted into it include: cover designs for cheap editions of Dickens; illustrations for Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her?; illustrations for a range of periodicals, across periodicities and markets; illustrations for Dickens’s monthly installments of Our Mutual Friend; Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice in Wonderland along with Mavor’s Spelling Book; Guy’s Spelling Book and Favor’s Spelling Book. We will conclude by thinking about what an almost entirely wordless album might show us about this high point of serial print culture in London that we had not seen before.

Isabel Seligman

British Museum

The executioner’s accomplice: capital losses and vital gains in the work of Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo remains one of the most celebrated authors of the nineteenth century yet despite producing in excess of three thousand drawings, for decades his graphic work was dismissed as little more than the inconsequential sketches of an amateur. Examining themes of crime and punishment which recur in Hugo’s writing and drawing, this paper considers Hugo’s radical depictions of execution, decapitation and disarticulation in light of theories of drawing as violence by thinkers including Hélène Cixous and Jacques Derrida. For Cixous any act of drawing is both a ‘cutting short’, a curtailing of potential, and a ‘melée’ in which violence is enacted, where it is all too usual for artist to play the part of both victim and executioner. Using these ideas as a starting point, the paper will examine the attribution, withholding, trading and soliciting of identity in Hugo’s writing and drawings relating to capital punishment, where heads can give a call to arms, and the guillotine is cast as both inhuman machine and willing ‘accomplice’ of the executioner.

David Skilton

Cardiff University

Millais’s pictorial capitals to The Small House at Allington

Millais’s decorated capitals for The Small House at Allington, which appeared at the start of each instalment in the Cornhill Magazine, are often overlooked for the simple reason that they were not reproduced in the first book edition of the novel — presumably on cost grounds. For much of the run of the novel, these vignettes appeared alongside Leighton’s vignette’s for Romola, and a comparison of the two sets of images is instructive. Millais’s show less pre-planning but arguably perform a great range of functions than leighton’s, and set up a reciprocal relationship with the text of a kind which is quite absent from Romola.

Lindsay Smith

University of Sussex

‘Awful lines’: Ruskin writing on drawing, engraving and daguerreotyping

In The Elements of Drawing published in 1857, John Ruskin alerts his reader to the ‘leading or governing lines’ that are ‘expressive of the past history and present action of the thing’. He urges his drawing students to ‘try always, whenever [they] look at a form, to see the lines in it which have had power over its past fate and will have power over its futurity’. In stressing those ‘awful lines’ as he calls them, Ruskin connects what the good drawing student should not ‘miss’ with a type of conglomerate temporal phenomenon characteristic of the recent invention of photography. The tendency inherent in such ‘lines’ resembles the propensity of a photograph to combine, in a unitary image, past, present and future states

Photography appears alongside engraving in Ruskin’s ‘three letters to beginners’ of drawing. While engraving is indispensable for the student of drawing in teaching properties of gradation, photography, like engraving, as a vital medium of reproduction, also provides access to exemplary forms of drawing. At the same time, however, photography complicates Ruskin’s account of line. Indeed, leading him to privilege what he calls ‘memoranda of the shapes of shadows’, photographs of architectural motifs had earlier helped Ruskin to capture the architecture of Normandy almost without line as in his pencil and brown wash drawing of ‘Notre Dame, St Lo’ that appeared as plate 2 in The Seven Lamps of Architecture in 1849.

This paper explores Ruskin’s drive to arrest ‘the shapes of shadows’ in the context of the monochromatic reproductive technologies of engraving and photography. Focusing upon The Elements of Drawing, it examines the importance Ruskin attaches to the relationship between ‘white surface and black shadow’ as photography re-stages the work (previously undertaken by engraving) to convey an experience of polychrome to the student learning to draw.

Bethan Stevens

University of Sussex

The Story of the Dalziel Archive, 1839-1893

The Dalziel Brothers had a phenomenal impact on Victorian visual culture, as Britain’s most substantial publishers of printed images – everything from Dickens and Trollope illustrations to fitness manuals, tobacco and chocolote adverts, the Alice books and Pre-Raphaelite wood engraving. In recent decades, the role of the wood engraver in the collaborative artworks they produced has received comparatively little attention. Over the last two years, the Dalziel Project has worked to catalogue and interpret the Dalziel Archive, and to make it accessible to scholars, artists and others. One of the effects of the Dalziel Archive is to put the wood engraver and his or her story squarely back into the works of art they created.

During their lifetime the Dalziel Brothers were highly sensitive to their public profile, as can be seen in two projects: one written, and the other determinedly non-verbal. The first is their publication A Record (1901), an autobiographical memoir about the family business, and the second is the Dalziel Archive, a visual archive of their entire oeuvre (around 54,000 prints), kept chronologically in albums and sold to the British Museum in 1913. Documentation at the museum suggests that the Dalziels were keen for their archive to be housed as a cohesive part of a national collection, willing to negotiate on price and timing to arrange this. In this paper, I compare the way the Dalziels present themselves textually in their memoir and wordlessly in their archive, examining both their writing and their album-making practices as distinct and sometimes contradictory reflections on their work. I reflect on the possibilities of reading an archive like this one as a single narrative, however messy and contradictory. As well as a story of a group of artists, it is a bewildering story of mass visual culture during a long period of enormous technical and cultural change. I read this meandering story, paying particular attention to the experience of family-based professionalism, looking at the way leading members of the Dalziel firm presented themselves. For example, they publicly downplayed the substantial contributions of women family-members, and anonymous wood engravers who worked in the Dalziel factory. I examine key clues in the archive to discover what it can tell us about the many individual engravers involved, their relationship with draughtsmen and other artists, and the dramatically changing experience of wood engravers over the five and a half decades Dalziel Brothers were in business.

Julia Thomas

Cardiff University

Affillustration: the Dalziel Digital Network

What does it mean to transform this album of wood engravings into a digital record? What are the implications of a transposition across media, from the bounded materiality of the book to the vacillating luminosity of the computer screen?

This paper argues that, in some ways, the Dalziel albums embrace and even anticipate this manoeuvre. Removed from their textual contexts and displayed side by side, the images in the album, like their digital surrogates, enable a different mode of viewing, a ‘looking across’ or ‘scanning’ of multiple images in which the adjacency of the illustrations signifies. This ‘scanning’ of illustrations reveals the affiliative relation between illustrations, the allusions and references to other illustrations, in a critical interplay that I call affillustration. Just as every text is a ‘tissue of quotations’ (to use Roland Barthes’ oft-recycled phrase), so every illustration is constituted by its references to other illustrations. In this sense, affillustration resembles its ‘intertextual’ counterpart, but it is distinct from intertextuality in its focus on the specificity of illustration and the different kinds of associations it instigates. Illustrations make meanings not just in their references to other illustrations, but also in the groupings and clusters that they generate, the ‘networks’ that exist within and across the boundaries of the illustrated album. Illustration is an eminently social genre. In both their physical and digital form, the Dalziel Brothers’ albums testify to this sociability, or what might be more aptly described as the ‘kinship’ between illustrations.

Kiera Vaclavik

Queen Mary, University of London

The Forgotten Alice Artists of the Nineteenth Century

It has become widely accepted that non-authorised revisionings of Alice within Carroll’s lifetime were both rare and inconsequential. Such is the view of John Davis (1979), taken up without challenge in Will Brooker’s influential study of 2003. In the passage from singularity to multiplicity, from Tenniel’s dominance to an open field, the turning point is generally identified as the copyright lapse of 1907. The vast majority of existing work on adaptation certainly focuses on the 20th and 21st centuries. Yet nineteenth-century revisionings were, I will argue, both (numerically) significant and wide ranging. Entirely overlooked by scholars to date, there was a veritable army of Alice artists in the nineteenth century: young and old, obscure and illustrious, amateur and professional. Isolated images of Alice extracted from the surrounding narrative produced in the 1890s show how artists such as Hilda Cowham and Edward Linley Sambourne were a;ready putting their own individual stamp on Carroll’s heroine. At the other end of the spectrum. amateurs in their droves were producing ‘copies’ of the Tenniel illustrations in a wide range of contexts and applied to diverse material supports, from envelopes and album pages to ceramic tiles. Although showcasing the artist’s precision, exactitude and fidelity to the original, these works by no means precluded creativity. Indeed, labelling them as copies belies the often complex and ingenious operations involved, including selection and reconfiguration. If a highly-restricted cast of actors (comprising Carroll, Alice Liddell, Tenniel and the Dalziels at a push) is usually invoked with reference to the production of Victorian Alice, this paper follows the example of the ‘Woodpeckings’ project to substantially extend that cast.