Brian Maidment is Professor of the History of Print at Liverpool John Moores University. His research interests are focused on the nineteenth century, especially mass circulation, popular and illustrated literature, and he has published widely on a broad range of topics, although more recently he has concentrated his interests on Victorian periodicals and early nineteenth-century visual culture. Brian Maidment will be speaking at our ‘Woodpeckings’ conference on 16-17 June.

My scholarly engagement with the history of the wood engraving in the nineteenth century, which has pre-occupied me for many years, emerged from reading Louis James’s magnificent illustrated anthology Print and the People 1819-1851 when it came out in 1976. I was struck by a number of factors. First was the visual impact created by the seemingly endless march of black and white images across the book’s pages – a combination of the inky blackness of the lettering, shouting display types and perpetually inventive combination of type, image and white page. Never had the printed page seemed so exciting. I couldn’t wait to get into libraries – if these texts looked so good in reproduction, what must the originals be like. Second was James’s choice of the period he used to frame his anthology. While ‘Peterloo to the Great Exhibition’ had a certain neatness it certainly didn’t align easily with those notions of periodisation conventionally used by historians. But in terms of the history of popular print this period made absolute sense to me. Another way of articulating this late Regency and early Victorian period in terms of the history of popular print might be ‘from The Mirror of Literature (1822) to the Illustrated London News (1842) by way of the Penny Magazine’ (1832)’. Or again ‘from the Northern Looking Glass (1823) to Punch (1841) by way of Figaro in London (1832) and The Penny Satirist (1833).’ Or, in another route map, from Life in London (1820-21) to The Pickwick Papers (1836-37) by way of Sketches by Seymour (1833-34). However considered, there is a strong argument for seeing the three decades that bridge the Regency and the Victorian period as a pivotal if not entirely coherent moment in the history of print culture largely distinguished, and indeed driven by, the presence of the transformative and newly ubiquitous presence of the wood engraving as a textual element.

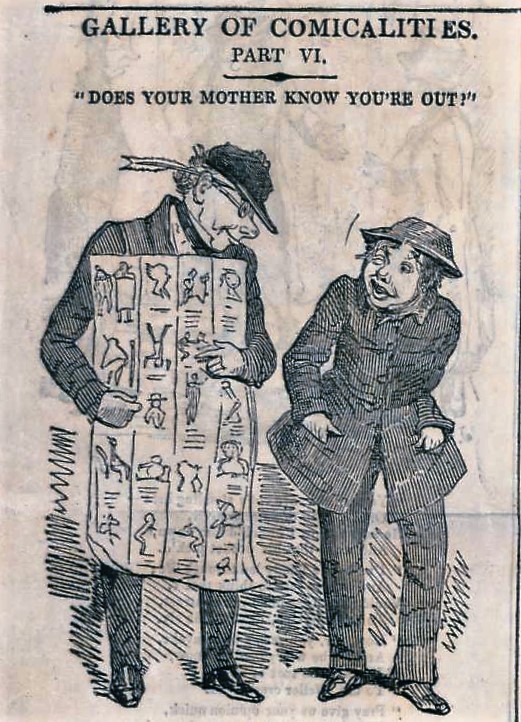

James was also prescient in assembling, in however unassuming a presence in his anthology, a huge cast of figures both real and imagined, that have formed the central levers that have allowed us to begin to prise open Regency and early Victorian popular culture – Tom and Jerry, Jack Sheppard, Charles Jameson Grant, T.P.Prest, The Literary Dustman, Robert Seymour and Varney the Vampyre among them. He also made clear the astonishing extent to which the black and white wood engraved image invaded print culture through a mass of different print forms and genres. The traditional vernacular forms that had always used wood engravings – broadsides, songsters, and almanacs for example – continued to be illustrated in traditional ways. But a major extension of the market place for the consumption of print among the just literate, the newly literate, the ambitious labouring classes and those in pursuit of instruction, diversion or pleasure meant that new or radically extended forms of illustrated literature were emerging, especially in the form of periodicals

James concluded his introductory chapter with the following comment: ‘We are left therefore with a paradox. The spread of literacy and cheap literature was widely associated with the demystification of the universe, and the substitution of a world of reason and objectivity. Yet both developments could assume dimensions as magical as the old beliefs they displaced.’ It is this tug between demystification and magic that still pulls me to want to look at the wood engraving, and especially at the mass of anonymous, largely functional and aesthetically unselfconscious or at least unambitious images that filled the graphic imagination of late Regency and early Victorian readers and spectators. He was right to call his chapter ‘magic into print’, a title that suggests both the way in which the world of superstition began to give way to a new information age in the 1820s, 30s, and 40s, and the ways in which cheap illustration brought something close to magic into print culture.