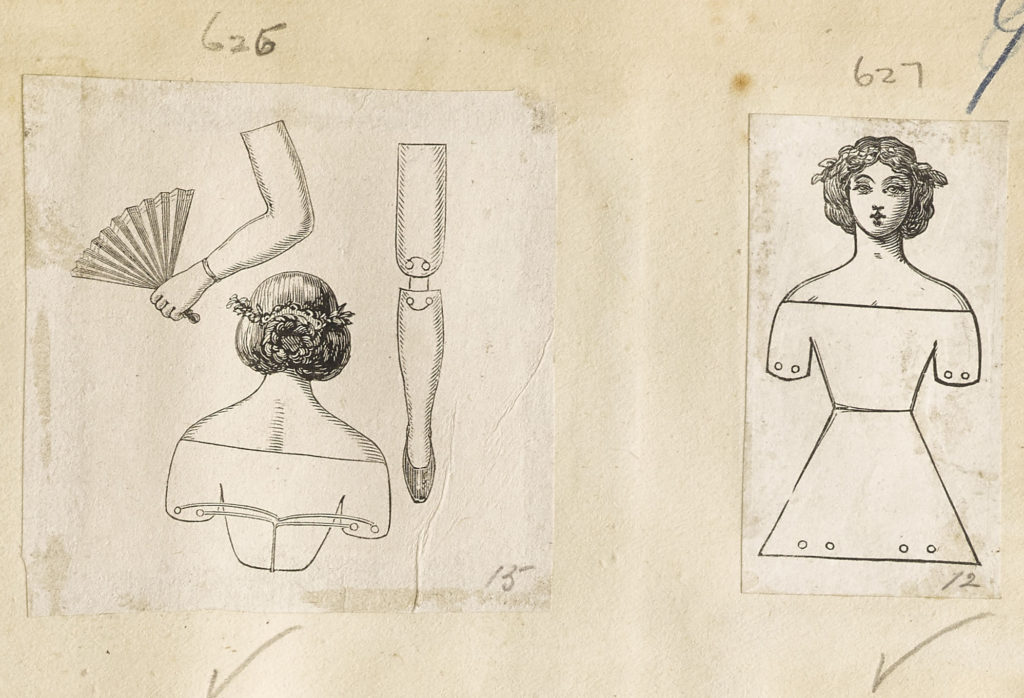

Heads, Shoulders and Whole Lengths, by Hannah Field, responds to the Dalziel image pictured below, an illustration for ‘To make dancing dolls’ from Laura Valentine’s The Home Book of Pleasure and Instruction, published in 1867 (see image 11 of Design in our exhibition). This piece was developed out of panel talks on the Dalziel Archive at the University of Sussex on 21st September 2016. Panelists – Hannah Field, Lindsay Smith and Nicolas Royle – each delivered a short paper, focussing on an image from the Alice to Alice exhibition that spoke to their research specialism. We will be featuring their responses on our blog in coming weeks, so watch this space!

~~~

In April 1764, George Alexander Stevens presented his Lecture upon Heads for the first time at the Little Haymarket Theatre in London. In this public entertainment, before the viewer’s very eyes, Stevens dressed papier-mâché busts as a succession of types—professional, national, urban, and bureaucratic—using wigs and other props. The performance became immensely successful. In fact, the Lecture’s popularity led to Stevens becoming so associated with heads that whole bodies posed a difficulty for him from then on: ‘a supplementary lecture on portraits and whole lengths,’ as Thomas Campbell tells us in his Specimens of the British Poets, ‘had no success’. I don’t know whether I will be any more successful in putting together the ‘whole length’ of this Dalziel image, which as you’ll see is of a jointed paper doll or puppet, but I’m going to try my best.

Putting together the image’s ‘whole length’ could be, for a start, a matter of context: laying the Dalziel doll alongside its many siblings. We could look to the actual material record of paper dolls—the Fuller brothers sold paper dolls called Fanny, Ellen, and Frank from their ‘Temple of Fancy’ on Rathbone Place in present-day Fitzrovia—but also by tracing the sometimes surprising cast of paper figures immortalized by the giants of nineteenth-century literature. In George Eliot’s most forbidding novel, Daniel Deronda brings paper dolls to little Adelaide Cohen, and helps her to arrange them ‘in their dance on the table’ while chatting with her parents. Robert Louis Stevenson scorns the boys who bought pre-coloured paper figures for toy theatres, instead of painting them by hand, and then drifts into an encomium to colouring-in: ‘With crimson lake (hark to the sound of it—crimson lake!—the horns of elf-land are not richer on the ear)—with crimson lake and Prussian blue a certain purple is to be compounded which, for cloaks especially, Titian could not equal’. Hans Christian Andersen’s tin soldier falls in love with a little paper dancer dressed in muslin and ribbons. And in his essay on childhood memories of toys, ‘A Christmas Tree’, Dickens finds something uncanny in the jointed pantin or Jumping Jack puppet, of which this Dalziel image is (I think) a specimen. ‘The larger cardboard man’, writes Dickens, ‘who used to be hung against the wall and pulled by a string’ had ‘a sinister expression in that nose of his; and when he got his legs round his neck (which he very often did), he was ghastly, and not a creature to be alone with.’ This cast of paper people brings a new angle to the question of what print looked like in the nineteenth century. Sometimes it had a face and body—even a fine floral crown, like the Dalziels’ figure.

.Looking at these Dalziel illustrations, though, I can’t help but think that parts can be much more intriguing than wholes. The illustration at right, for instance, turns a form that is often high-status and designed to last—the bust—into something miniaturized, much slighter (this is a children’s toy) but also more intimate. Intimate because the young lady appears scantily clad, with only a few lines to hide her modesty. (She’s not bad, she’s just drawn—or rather engraved—that way, to quote Jessica Rabbit.) But also intimate because at this stage in production the doll is unfinished: a piece of DIY, if you will. Seeing the parts laid out side by side, before they become a ‘whole length’, gestures towards the nineteenth-century predilection for what the historian Ellen Gruber Garvey calls scissorizing—cutting up paper and assembling it into something else. The little holes, which show where the torso should be pierced to add new parts, are printed on the page, and it’s up to us to pierce them and put the doll together. It’s also up to us (like Stevens, dressing up his busts as a London blood or a connoisseur) to decide what this girl should be—how will she look, once she’s assembled? What will she be?

Parts from wholes can be uncanny, then, as Dickens suggests, but there’s nothing of this about the Dalziels’ paper woman. She seems, like Andersen’s ballerina, to be a dancer—her well-moulded leg at left looks ready to kick, her arm looks ready to wave its fan, and her Bardot neckline also hints that she might become (once assembled) a dancing girl. The Jumping Jack is a toy that’s well suited to representing dance, not just because it can actually be made to move, but because the quality of that movement combines the organic with the mechanical, the carefully practiced with the seemingly spontaneous—just like skilled dance.

And, what’s more, this doll and her constituent parts give us a way to think about the Dalziel albums that are explored in ‘Woodpeckings’. The albums provide lots of larger publications, cut up into parts and reassembled in unexpected ways, much as this doll demands us to do. These albums, which are professional records, nonetheless retain an aesthetic of juxtaposition that might be traced through other ‘scissorized’ productions in the nineteenth century; they hint at the scrapbook or the parlour album. And in these albums, as in the scrapbook tout court, the parts seem just as evocative as the whole.