I have been very fortunate spend recent months curating Beyond the Archive, an online of critical and creative writing drawings and prints by Year 7 students of Brighton Aldridge Community Academy (BACA).

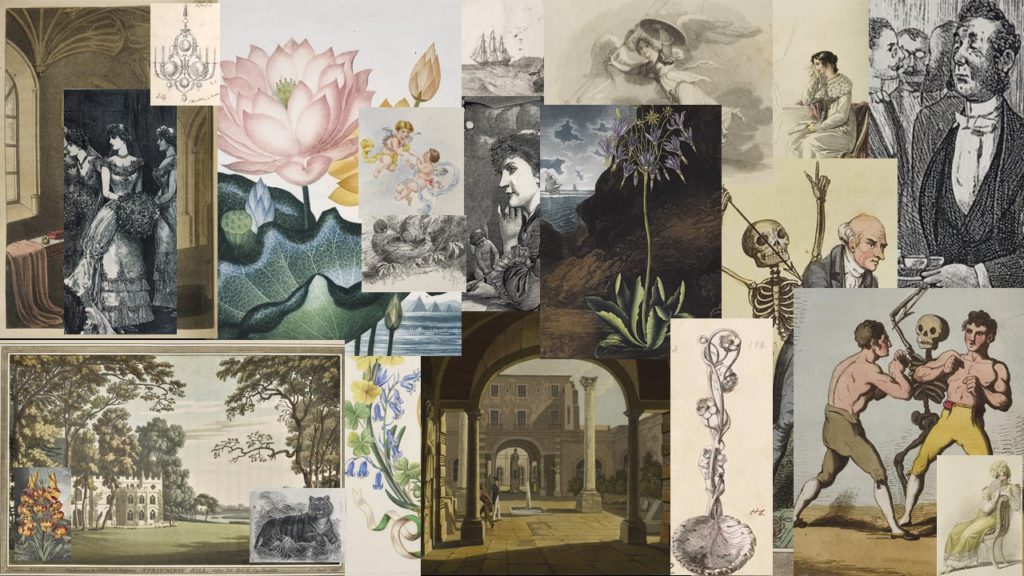

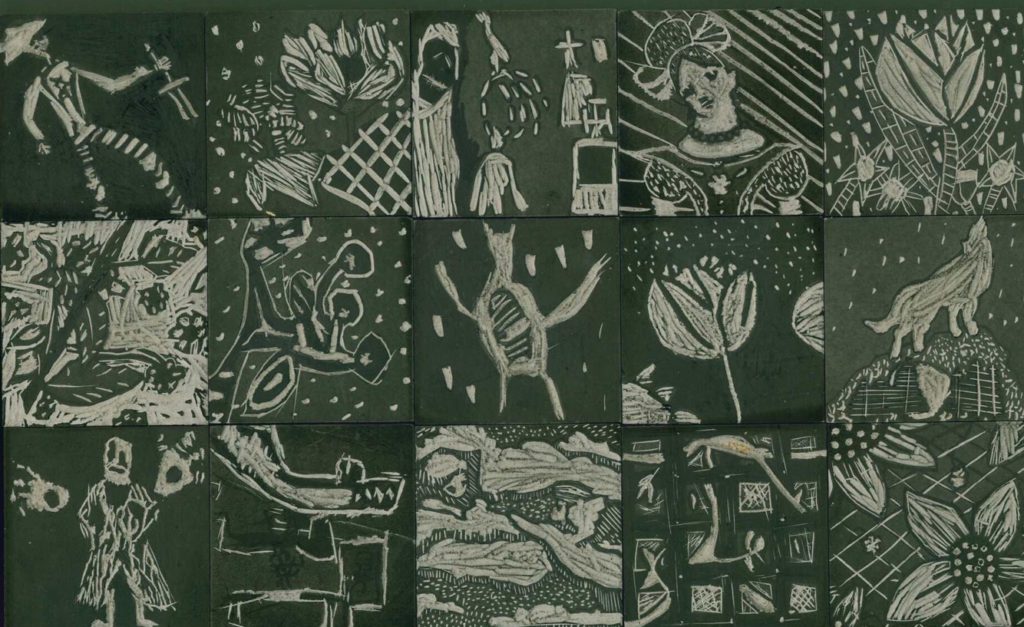

This group is undertaking a series of structured workshops (to resume when the school re-opens) devised by teachers Lauren Howfield and Emily Jewell, and academics Dr Bethan Stevens, Dr Hannah Field, Dr Treena Warren and Professor Lindsay Smith of the University of Sussex English Department. On a field trip facilitated by Archivist Richard Wragg at The Keep, Brighton, they saw rare books dating from the late eighteenth to the late nineteenth century. They engaged with what they had seen by writing short descriptive and creative pieces. In a second workshop with guest artist Peter S. Smith, they created lino cut illustrations inspired by the illustrations.

I became aware of the Dalziel Archive, the Woodpeckings website and Dr Bethan Stevens’ research while cataloguing nineteenth-century collections in The British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings. The connection between my own cataloguing and Beyond The Archive has caused me to reflect the physical and digital dimensions of archives, how they might conserve historical material and shape the future.

The closure of schools and universities during the Covid-19 crisis has brought digital collections into focus. Museums and libraries have had a role to play in enabling home schooling and independent research through virtual exhibitions, blogs and online collections. Viewing an artwork or book in an online catalogue or database can be an end in itself, raising awareness and understanding of an object that would be inaccessible otherwise. However, it can ideally be a first step on a journey to encounter a physical object. Going beyond the open access areas of libraries and museums can be a powerful and formative experience.

One student of BACA described visiting The Keep and learning to create lino prints as an educational experience that was also individual, creative and emotional:

“I have learnt so much from this project. I thought it would be easy to make these prints. It wasn’t at first but when I got the hang of it, I was happy with the outcome.

The first session was a trip to The Keep, I learnt all about the interesting prints they did in the Victorian time. All the hours of detail are really effective and inspiring. I enjoyed looking at the old books that used the printing techniques.

The second lesson was by far my favourite. I went on a trip to Sussex University. It was really fun because I got to create my own art and turn it into a print. I created a bunch of flowers, I’m very proud of what I created.”

Another student described making a linocut in verse:

“We used our artwork to create a print

It was a slow process not a sprint.

We traced it on to the lino

We cut very carefully

The results came out perfectly.”

This type of project has a number of important learning outcomes. Primarily, it introduces the students to the idea of archival research. In a world where we increasingly seek information online, the workshops highlighted the difference between seeing books as physical objects with what can be learned about them on the internet.

The written component of the workshops also engaged students with the many possibilities of research. The books that they looked at connected with diverse areas of knowledge including economic, political and cultural histories and developments in science, geography, classics and literature. Students were empowered to use what they had seen and read in their own writing and artwork. Finally, their research was linked to a creative but nonetheless systematic and mechanised process of printmaking which engaged skills in design and technology. Students were also able to see some of the collections available in their local community and form an impression that the archive at The Keep was an open and welcoming space. Bethan Stevens comments that they were proud to be trusted with rare books and excited to be able to handle “amazing objects from the past.” Importantly, these workshops have made archival research part of general education offered to all students, including those who don’t specialise in arts and humanities or pursue academic study beyond GCSE.

Rather than being a case of academics imparting information to students the workshops were a two way street. Seeing how young people engage with the archive has great learning potential for specialists. Perhaps some of the best insights into the nineteenth-century worlds of word and image can be offered by the younger generation who have always known the internet and social media. Like them, nineteenth-century viewers were presented with a dizzying array of images through new media. Sentimental, newsworthy, historical, scientific and fantastic illustrations vied for their attention in newspapers, illustrated books and periodicals, equivalent to today’s magazines.

Academics, archivists and artists can reconnect young people to the aspects of the nineteenth century that are less relatable today, the painstaking process of creating wood engraved illustrations and the intense, wordy descriptions that surrounded Victorian illustrations. Meanwhile, young people can give us insight into how a world of contrasting images can be navigated. The ways that students saw, interrogated and responded to nineteenth-century illustrations have set the agenda for this exhibition. Curating their work in the Beyond the Archive exhibition presented many observations, questions and directions to me which I had not previously considered. It also bought a greater sense of exploration, fun, humour and enjoyment of the material as a result of its having been seen anew.

The importance of those early experiences of visiting archives and special collections are evident to me. As an undergraduate student, I was introduced to the Prints and Drawings study rooms at The British Museum and Windsor Castle and was amazed to discover that by simply making an appointment, I could sit within inches of such treasures as a book illustrated by William Blake or drawing by Raphael. This was educational of course but moving too, offering a deeply embodied and intimate connection to the past. Years later, when teaching students about iconic garments in the splendid space of the V&A’s Clothworkers Centre and on “behind the scenes” tours with curators at the Museum of London, I was happy to pass this on to another generation. Such close-up experiences of researching hold many possibilities for learning and creative inspiration and for building connections and communities. Yet because archives are often kept behind closed doors or open by appointment only, they can be little known about or seem daunting to enter.

Meanwhile, those objects kept outside open access or public display can be the most difficult to engage with, they may be fragile or challenging to exhibit, too lengthy to consume in one sitting or too subtle to grasp the attention.

The ‘Woodpeckings’ website itself enlivens a multi-volume collection of Victorian proof prints which range from Pre-Raphaelite illustrations to comic books and adverts. the prints are pasted chronologically into large volumes and kept in the British Museum’s collection. To know of the Dalziel Archive’s existence, to be able to search within it, to understand what it was for in context and to see its research value and possibilities today is by no means easy or “natural” even to researchers. To navigate such a collection relies on a skill set that must be learnt and, in my own experience, was only introduced at university and actually used in final year undergraduate and postgraduate studies.

Indeed, the popular culture of one era, like illustrations published by Dalziel, can become the most obscure and difficult to access centuries later. Those printed images that many people saw and understood immediately everyday are often the very things that are archived out of sight, their visual appeal, contexts, meanings and terms of reference lost in time. The workshops pioneered by the University of Sussex offer important lessons into how such material can be made truly accessible again. These strategies also show that the rare books perhaps seldom seen as a result of having moved from private collections into library archives can be opened up to be a source of interest and excitement for students today.

Virtual collections and websites like this one offer much. My own research for the exhibition has been indebted to online resources from the University of Edinburgh Library and Wellcome Collection. However, in an ideal world, online information is best used alongside school trips, research appointments, exhibitions, displays and workshops. Furthermore, it is apparent that access to computers for study is not available to all.

Being without museums, galleries and libraries since March has heightened our appreciation of visiting collections and seeing objects made and handled by people centuries before us. We are also increasingly aware that access to learning and collections must be a truly inclusive experience. Hopefully, the reopening of schools and collections will allow the University of Sussex to continue to introduce this important lived dimension of archival research to primary education and will inspire similar projects.

Susannah Walker