Elle Whitcroft is a PhD student in the English department at the University of Sussex. Her research looks at late nineteenth and early twentieth century newspaper comic strips in the US and UK, focusing on childhood, dreams and racism. Here, Whitcroft reviews Simon Grennan’s Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval, available now at bookworks.org.

Elle Whitcroft is a PhD student in the English department at the University of Sussex. Her research looks at late nineteenth and early twentieth century newspaper comic strips in the US and UK, focusing on childhood, dreams and racism. Here, Whitcroft reviews Simon Grennan’s Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval, available now at bookworks.org.

Remembering Marie Duval

As a female PhD student working between comics and literature, it comes as no surprise to me that Marie Duval’s story was one of erasure. Women’s work has long been diverted, stolen, erased. Marie Duval (real name: Isabelle Émilie de Tessier) was a Victorian artist and performer whose work and illustrations, according to the Marie Duval Archive, amounts to approximately 950 pieces. In the past, it was sometimes denied that Marie Duval was a key contributor to the popular comic strip character Ally Sloper. Throughout their recent research on Duval, comic historians Simon Grennan and David Kunzle have stepped in to re-establish Duval’s authorship as central and irrefutable.

It was not uncommon for comic strips to pass from one hand to another; indeed, the late nineteenth and early twentieth century saw U.S. comic artists flit between the newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, often dependent on pay and artistic freedom. However, Marie Duval’s work, until the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, was all but forgotten, since male artists (her husband in particular) overshadowed her contribution. It has even been suggested that Marie Duval was a man, using a pseudonym. But, as Simon Grennan highlights in his latest graphic creation, Drawings in Drag by Marie Duval, nothing is quite as it seems.

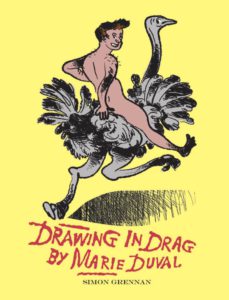

Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval by Simon Grennan

Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval by Simon Grennan

In Simon Grennan’s new book, Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval, allegories and idioms push through each illustration, capturing the conventions which brought comic strips to popularity in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. As the title suggests, this book is both a self-reflexive and critical book. By adopting the name Marie Duval in his title, Grennan acknowledges the complications behind Duval’s pseudonym. More critically, the book responds to Duval’s drag history, which saw her performing as a cross-dressing man on stage alongside her illustrative career. This performativity and ever-shifting presentation of identity is drawn out in Drawings in Drag by Marie Duval, underlined by contemporary readings, such as: queer street stylization, urban hieroglyphs, and Japanese androgyny. Then, this book also sits as a statement on queer culture and takes on a more pressing significance in remembering Duval. The book also nods to Duval’s freely flowing, organic lines and shadowed backgrounds, as Grennan remembers Duval’s work through his own. Grennan’s other work on Duval includes Marie Duval: Maverick Victorian Cartoonist, Marie Duval (co-authored alongside Roger Sabin and Julian Waite), as well as the online Marie Duval Archive (co-edited with Laurence Grove).

Grennan’s work addresses the almost-lost history of Marie Duval by paying homage to her ‘one-shot’ illustrations, which were designed to make a statement. The book, a series of themed visions with terse, suggestive captions, adopts and harnesses the delight in fashion and gimmick that popularised Duval’s work. Through a series of social observations, Grennan captures quiet, modern-day allegories. This is very similar to what Marie Duval drew in the early Ally Sloper character. Quickly rising to fame, Ally Sloper was a contradictory man (Alexander ‘Ally’ Sloper), who truly ‘slopes’ about the place, sticking his nose where it doesn’t belong. Although Grennan’s text takes a more critically observant stance, the book captures the comedy which punctuated Duval’s work. Prominently, the animated characters (and objects) all have shadows, which sport unbroken, ‘scribbly’ lines—a style of Duval’s which perhaps predicted the thought bubble scribble, illustrating puzzlement, or frustration or disorientation.

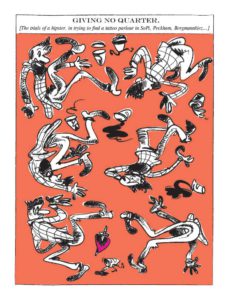

All seriousness aside, this is a fun book; it provides snapshots of modern-day idiosyncrasies. My favourite page is titled ‘Giving No Quarter {The trails of a hipster, in trying to find a tattoo parlour in SoPi, Peckham, Bergmannkiez}’, which depicts several different bearded men in plaid shirts, free-falling through space at different angles (see Fig. 3). This scene is intermittently sprinkled with black coffee, wrenched from the hipster’s hands during their fall of despair (the coffee is presumably organic trade). Another interesting sequence shows six individuals in varying voguish outfits, posing against a wall (see Fig. 4). Their shadows, instead of echoing their bodies, form a series of flowers, suggesting an organic, natural aesthetic.

Overall, this book is a delightful way to engage with the work of Marie Duval from a modern perspective. It demonstrates, through careful craft and comedy, the richness, depth, and complexity that old cartoons held, whilst reminding us (students, artists, fans) to continue reanalysing and observing art from the past.