Emma Newport is a Teaching Fellow at the University of Sussex, having previously been a Research Fellow at King’s College London. She is interested in eighteenth-century attitudes to China and, more broadly, in women’s positions in a network of global exchanges of ideas and objects. Emma teaches Romantic poetry, with a focus on lyric poetry, William Blake and women writers; Jane Austen and her fellow women novelists in context; and creative writing.

Emma recently organised a conference at King’s College London on “Women, Money and Markets (1750-1850)”; the main speakers were Professor Hannah Barker (University of Manchester) and Caroline Criado-Perez OBE, a campaigner for women in the media. Please see womenmoneymarkets.co.uk for further information.

White Knights and Errant Engravings: Reading the Horse in Dalziel

An anxious eye fixed on Alice, the White Knight’s horse piaffes – or, more accurately, passages – elegantly beneath a jumble of equipment so numerous that saddle and numnah have almost been obscured. With a nicely developed topline (the neck and back muscles that are exercised to increase the strength, balance and condition of the horse), the grey is presented in a slightly overbent shape to emphasise his power and refinement. The movement is very much that of a highly-trained cavalry horse. Mid-nineteenth-century equestrianism developed piaffe and passage for the parade ground in order to demonstrate the skill of the rider, as well as the power, suppleness and obedience of the horse. As the cavalry instructor John Adams noted in 1805:

These high airs [such as passage and piaffe] are ornamental; as such, many are proper for parade, and when a commandant displays a proficiency in horsemanship, it portends the regiment will profit much by his discrimination and selection of proper and capable persons to ride it; for without he is a horseman himself, he can be but a very indifferent judge of others, unless their abilities are extraordinary, and very conspicuous, which is rarely to be met with.

John Adams, An Analysis of Horsemanship: Teaching the Whole Art of Riding, in the Manege, Military, Hunting, Racing, and Travelling System. Together with the Method of Breaking Horses (1805).

Take a look at an example of passage here: note the elegance of these movements and the military aesthetic of the Spanish Riding School, whose classical dressage performances are the closest modern equivalent to mid-nineteenth-century equestrianism.

Passage:

The movements of the White Knight’s horse in the engraving should be based on the precise balance of the rider. Again, Adams describes:

Now the distinguishing qualities of the piaffe from the passage, are a straighter position, loftier action, slower time, and the plying of the haunches … The riding of this air requires the balance to be very true … The horse must advance a little at every bound, and the action is extremely rough and difficult for inferior horsemen to preserve a true balance.

However, it is quite clear that the horse’s military precision as it moves through the space of the engraving is directly at odds with both his rider’s imbalance and the textual description of the White Knight in Carroll’s work.

The White Knight in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through the Looking Glass (1872)

The White Knight of Carroll’s Alice story is a singularly incompetent horseman. His failure as an equestrian is typified by his inability to find any balance and by the regularity with which he falls:

Whenever the horse stopped (which it did very often)… fell off in front; and whenever it went on again (which it generally did rather suddenly), he fell off behind. Otherwise he kept on pretty well, except that he had a habit of now and then falling off sideways; and as he generally did this on the side on which Alice was walking, she soon found that it was the best plan not to walk quite close to the horse.

In an echo of the title of Adams’s treatise on horsemanship, the White Knight begins to polemicise on ‘The great art of riding’, which, he says, ‘is to keep—’: and there his view on the art of riding is arrested, as he is interrupted by a further fall. Either way, the Knight is clearly a rank amateur and one who would be incapable of producing the collection and precision of aid required to create the elevated action of his horse.

The engraving of the White Knight’s horse shows an open-mouthed animal, literally champing at the bit: the flaring nostrils and stress veins indicate the flood of cortisol and adrenaline and the pumping heart beneath the clanking junk and haphazard rider. The depiction of the White Knight’s horse is, therefore, very far from the description that Alice gives, as she remarks, ‘And how quiet the horses are!’. As she joins the White Knight for a section of the journey, she observes the tranquility of the horse, noting ‘the horse quietly moving about, with the reins hanging loose on his neck, cropping the grass at her feet’. As the interlude concludes, the White Knight disappears from view, his ‘horse walking leisurely along the road’. None of this genteel and languid behaviour is reflected in the enervated action of the horse in the Dalziel engraving. The engraving of the horse itself is shaped by jagged, pointy things, from the spikes around the horse’s fetlocks to the splinters of carrot-shaped items (possibly actual carrots) hanging from the saddle. It gives a strange impression of percussive and discordant noise and of discomfort and clash, all of which distances the illustration from the text.

Why this gap between engraving and novel?

The White Knight of the Carroll text can be read as a representation of Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, the man behind the pseudonym Lewis Carroll: the mad inventor and chaotic individual is, perhaps, captured in the character of the White Knight. (See Rackin in Textual Bodies: Changing Boundaries of Literary Representation [1997]). The frontispiece engraved by the Dalziel brothers bears little relation to Dodgson in appearance.

Instead, the White Knight is depicted in the frontispiece with a prominent nose and generous moustaches, whilst his horse’s passage echoes the statuary that dress the urban landscape and stand in requiem for a fallen hero.

My main impression when looking at White Knight is one of a more overtly military image, which in turn suggests that the Dalziels’s collaborator and designer Tenniel may have been engraving with images of the Franco-Prussian war in mind. In particular, the appearance of the White Knight seems to resemble most closely that of Napoleon III.

The Dalziel brothers and Tenniel were acquainted with war correspondents such as Gordon Thomson, an artist, and with fellow artist and correspondent Professor Hubert von Herkomer, R.A. Their creative circle overlapped with government ministers and war correspondents and so were familiar not only with the images of war and the role artists played in reporting it, but also with the workings and, it is intimated, opinions of those at the War Office in London.

A French Betrayal

Despite a recent alliance with France in Crimea, Britain did not participate in the Franco-Prussian war – in part because Gladstone was reducing public spending and military expenditure was low. More seriously, the German Bismarck had leaked to the British a document given to him by the French ambassador to Prussia after the Austro-Prussian war, which stated that France would not obstruct Prussia’s chauvinism in return for France’s possession of Belgium and Luxembourg: a direct violation of the Treaty of London (1839) which guaranteed Belgium and Luxembourg’s independence.

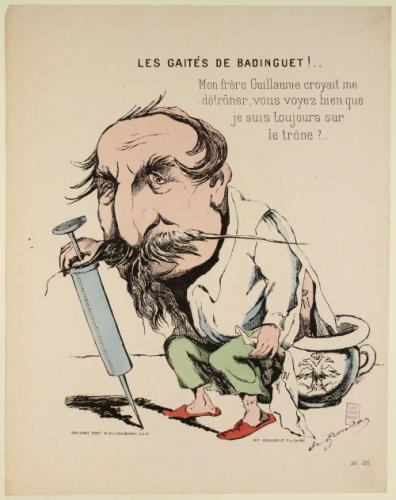

France had betrayed Britain and her allies in a manner that revealed weakness and self-interest; French satirists, including Charles de Frondat (see image), also regarded Napoleon III’s capitulation at the close of the war as a betrayal of France.

This, then, brings us to the matter of the frontispiece.

By choosing to depict the White Knight’s horse with a typically military movement and attitude, rather than illustrate the gentle ambling of Carroll’s equine, I wonder if Tenniel and the brothers Dalziel sought to mock the incompetence of Napoleon III and his lily-livered, white-flag-waving capitulation that led to the suffering of the ordinary French.

By choosing to depict the White Knight’s horse with a typically military movement and attitude, rather than illustrate the gentle ambling of Carroll’s equine, I wonder if Tenniel and the brothers Dalziel sought to mock the incompetence of Napoleon III and his lily-livered, white-flag-waving capitulation that led to the suffering of the ordinary French.

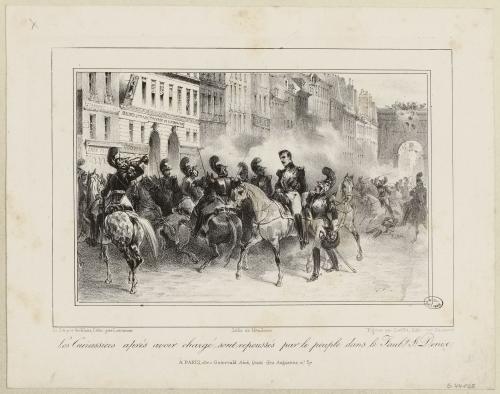

The frontispiece for Alice Through the Looking Glass (1872) parodies the iconography of war and its fetishistic memorial to the powerful and the dead. The saddles and packs used by the French and Prussian militaries (see image below of cuirassiers) are very much reminiscent of the Dalziels’s engraving of the White Knight’s equipment. The cuirassiers who fought on both sides were the cavalry soldiers who once wore cuirass, a piece of armour consisting of breastplate and backplate fastened together, and so very much the descendants of the old knights in armour.

Tenniel’s drawing depicts the inadvisable thrusting nature of a ruler destined to fall in a parody of the drawings and engravings that came back from the Franco-Prussian war in 1870 and 1871, right as the Dalziels were working with Tenniel to produce Alice Through the Looking Glass. As the White Knight fell repeatedly from his horse, so Napoleon III fell from grace and power: the Franco-Prussian war concluded with Napoleon III’s surrender, despite the humiliated Emperor declaring that he ‘would have preferred death to a capitulation so disastrous’ (Letter to Empress Eugenie, 2 September 1870). The piaffing or passaging equine becomes a totem of the false chivalry of war: the engraving captures the absurdity and the incompetence of Napoleon III driving noble men and animals into ignoble folly and disaster and the repeated tumbles of the White Knight a personification of the failures of a French emperor.