Georgina Grant is a Curator for the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, based at Blists Hill Victorian Town. Her role is varied, ranging from the development and delivery of the interpretation of the 52-acre site, to installing Quaker costume displays and giving talks on a traditional Victorian Christmas. Georgina will be speaking further on the research presented here at our Woodpeckings conference in June.

Uncovering the Coalbrookdale Company catalogues: Ironware and Illustration

First appearing in the 1750s, illustrated trade catalogues became popular as a way for industries to promote their goods as desirable products. In the Victorian period, trade catalogue production boomed. Mass manufacture meant mass marketing, and increased competition between companies fuelled the growth in advertising.

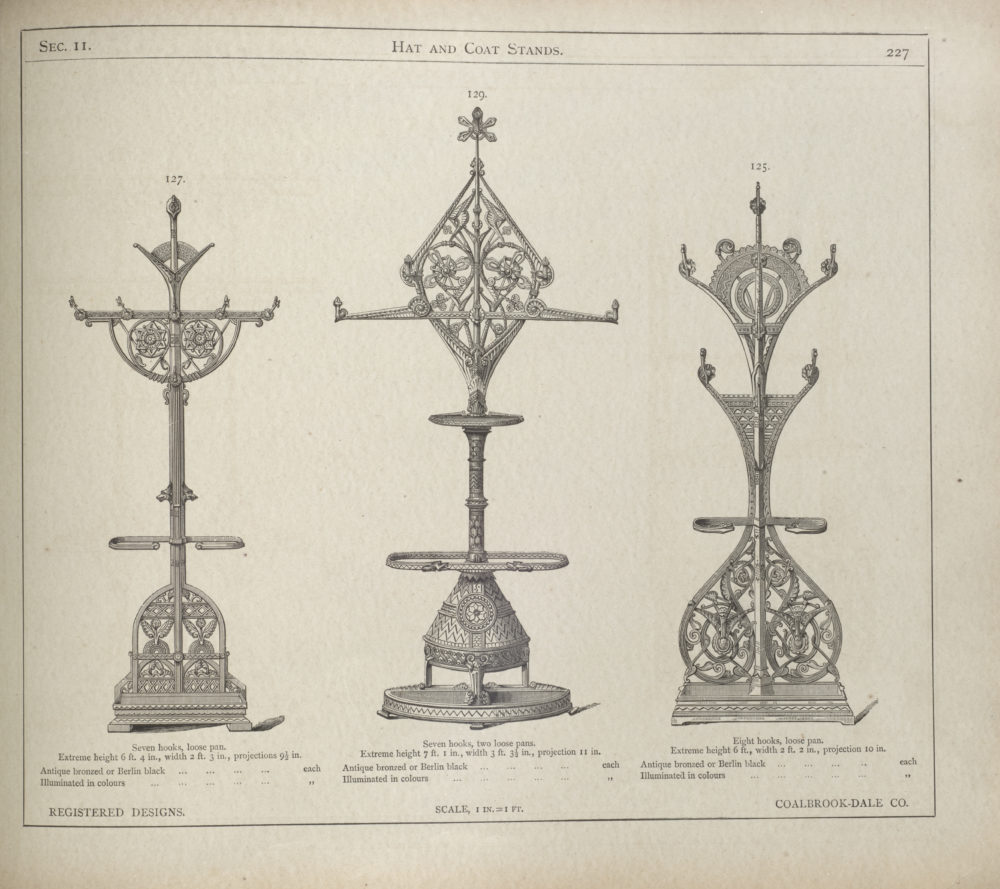

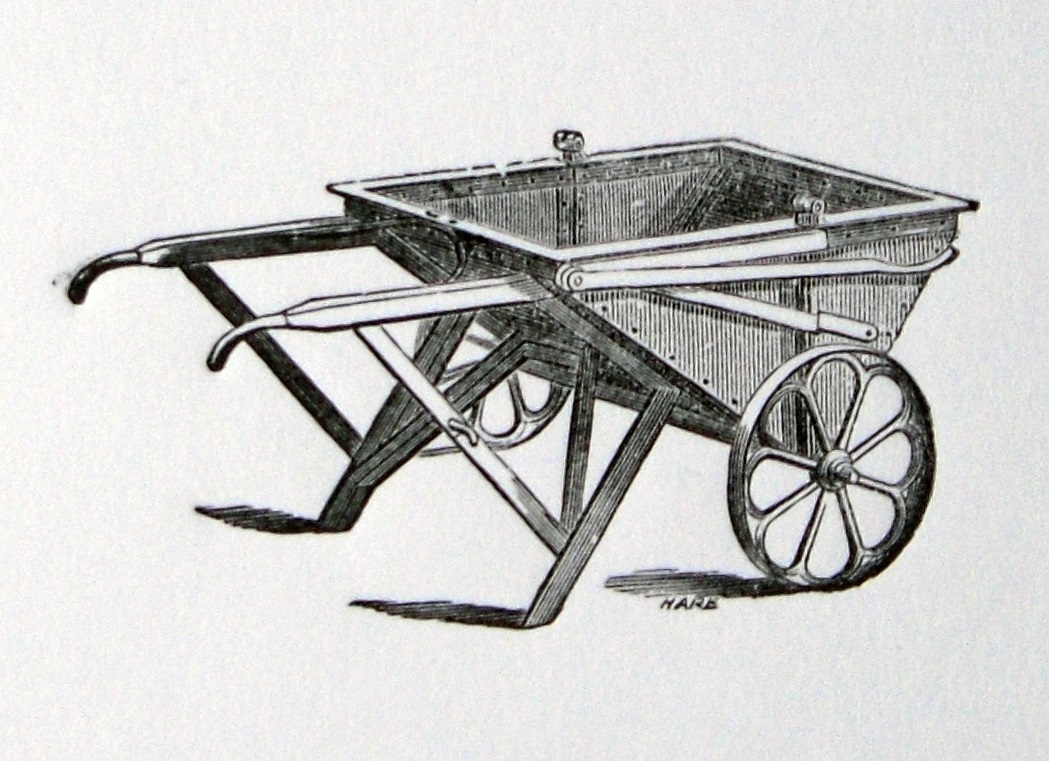

Catalogues evolved from small pamphlets to multi-volume books with thousands of illustrations. Iron foundries were one of the first trades to produce illustrated catalogues, and their conviction that anything could be cast in iron was reflected in the endless variety of objects for sale. The Coalbrookdale Company, a long-established ironworks, produced a colossal catalogue in 1875 (figure 1). It consisted of two volumes totalling 1,032 pages, and some items, such as gates and railings, fireplaces or kitchen ranges, were available with hundreds of different designs to choose from.

Catalogues were printed at great expense and to the very highest standards. They were available for viewing in company showrooms, as well as distributed to shops such as ironmongers. A number of now almost forgotten Victorian wood engravers illustrated these catalogues, which were rendered with the same respect and accuracy as any piece of fine art.

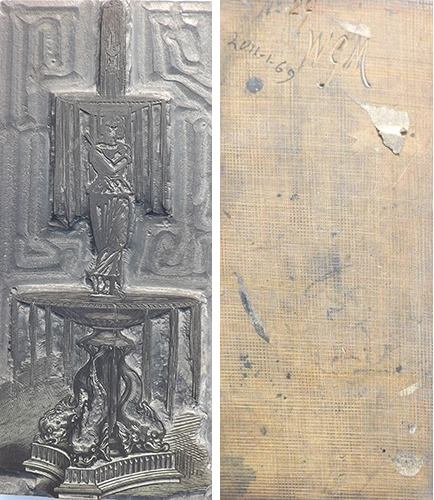

In an attempt to understand more about the blocks, I contacted the British Museum, who put me in touch with Bethan Stevens, a Lecturer at Sussex University working on a collaborative project with the Prints and Drawings Department of the British Museum. During a visit to the Ironbridge Gorge Museums to see the collection, Bethan pointed out that some of the woodblocks featured the engraver’s signature. More often than not, signatures on woodblocks refer to the engraving company or the artist who designed the illustration (figure 2). On the rare occasion however, woodblocks were signed on the back by the engraver themselves, something which has been revealed through Bethan’s research. One such signature discovered on this visit was ‘WGM’, written on a block illustrating a Coalbrookdale Company fountain that appears in their 1875 catalogue (figures 3 and 4). The signature indicates that the engraver may have been Walter George Mason (fl. 1842-57). If the signature is indeed that of Mason, then the block is of an earlier date than previously thought, and as such, potentially used to print an earlier catalogue. This is not so surprising. Ironworks often produced the same products over a number years. Items Coalbrookdale made for the Great Exhibition in 1851, for example, were still available to purchase in their 1875 catalogue. Mason also engraved woodblocks for the Illustrated London News and Punch, hinting that Coalbrookdale hired some of the best engravers of the day.

Very few company records of ironworks survive, Coalbrookdale included. Existent catalogues and thus the processes made to produce them are an important record of the workings and practices of iron foundries. Many trade catalogues have not survived into the 20th century, perhaps destroyed in favour of the latest edition, or not deemed ‘important’ enough to collect. The signature of ‘WGM’ gives tantalising clues of lost catalogues, the process by which catalogues were produced, and the lives of those who made them.